Sometimes called the “last organ under active research”, the human microbiome and therapeutics relating to it are attracting dollars and interest in the innovation community – albeit still from a low base.

While we have been aware of microorganisms since the discovery of the microscope in the 17th century, it is only more recently that science has become aware of the complex interactions of different microbes hosted by humans and the effect they have on our bodies.

The idea that the collection of microorganisms living on the human body have an influence on our health and immune function has become popular in the healthcare sector. Sometimes called the “last organ under active research”, the human microbiome and therapeutics relating to it are attracting dollars and interest in the innovation community – albeit still from a low base.

According to Strategic Market Research, the human microbiome market worldwide is expected to witness a robust CAGR of 31%. The market itself was, according to the report, valued at merely $115m in 2021 but is expected to reach $1.3bn by 2030.

Another report from ResearchandMarkets, put the 2022 microbiome market higher — at $390m — and forecast it would grow to $570m by the end of 2023. That is miniscule compared with, say, the global oncology market estimated at $286bn in 2021, according to a report by Precedence Research. The market for microbiome-based treatments is still nascent.

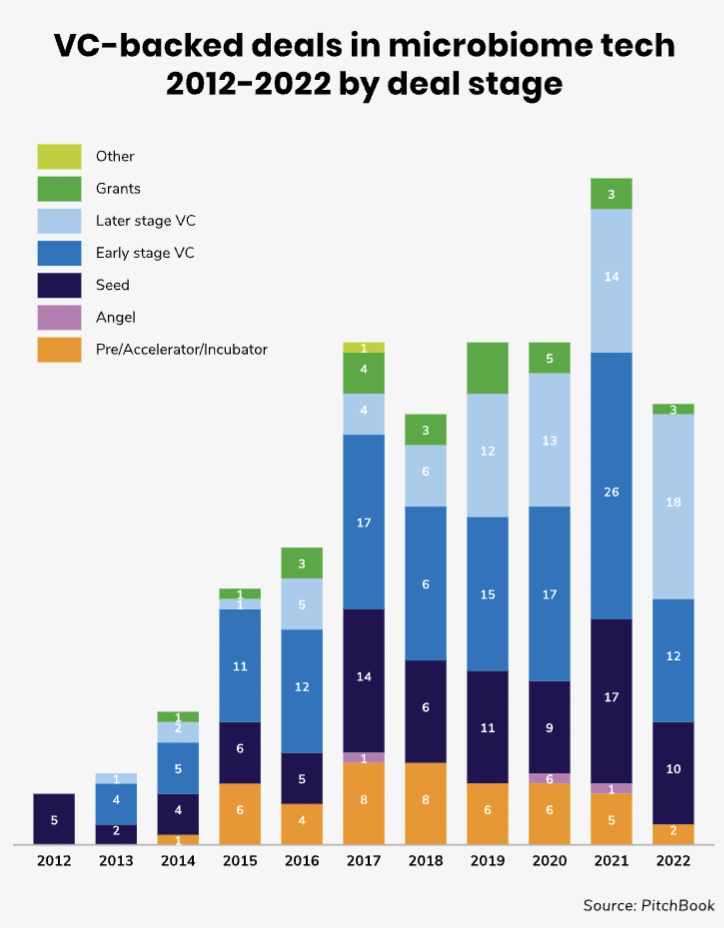

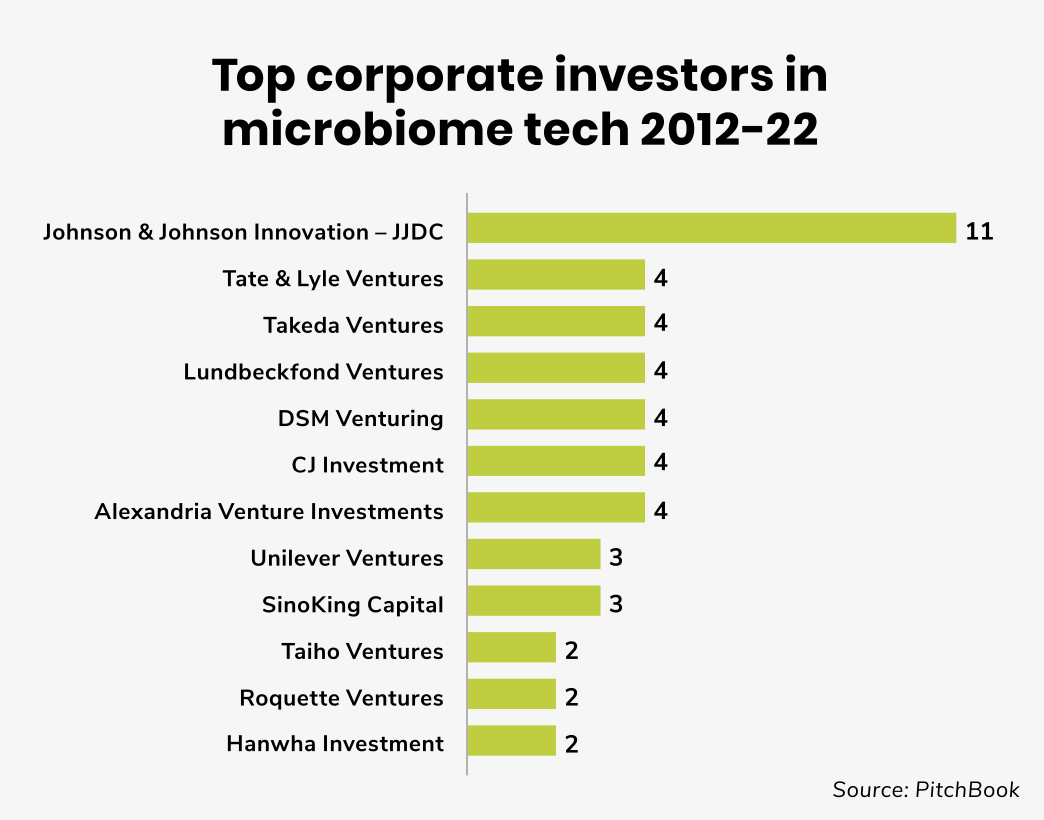

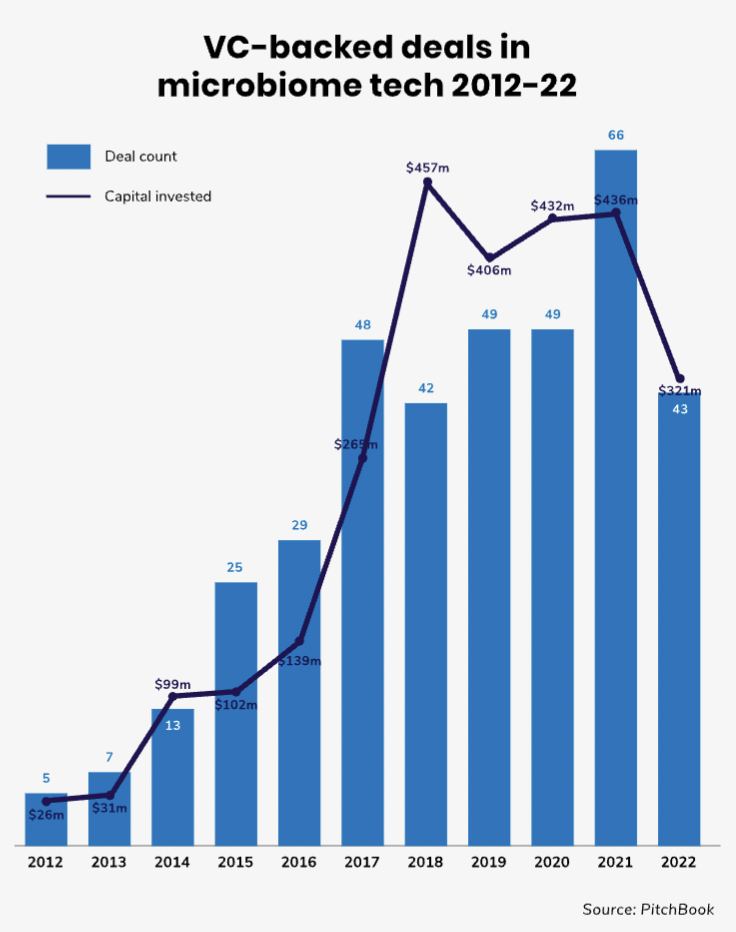

The number of VC-backed deals in the human microbiome space is still relatively modest even on a global scale as the above chart illustrates. Moreover, it is not an area with a great deal of corporate investment — the share of corporate-backed deals in this field is less than 20%.

Johnson and Johnson Innovation – JJDC has been one of the most active corporate investors into microbiome startups with 11 deals in this space in the last decade. Last year, for example, the venturing arm backed the $35m series B round raised by Locus Biosciences. The company develops precision medicines for bacterial infections and microbiome diseases, designed to tackle growing antimicrobial resistance.

Most of the funding rounds that have gone ahead are at the seed or early stage. Median deal sizes are relatively modest — just $4.5m last year and the median post-money valuations of the startups raising

the funding tends to be low.

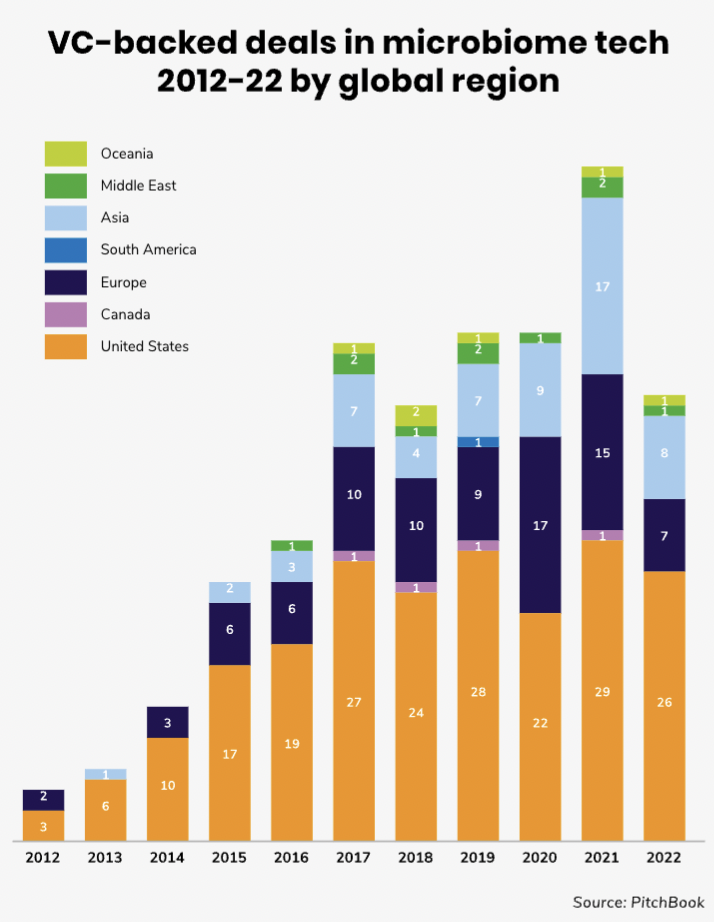

North America and Europe have been the biggest regions for microbiome funding rounds, although there is an increasing number also in Asia Pacific.

Gut feeling

Microbiota, depending on where they are located, can be subsumed broadly into respiratory, oral, gut and skin microbiota. Gut bacteria is the most studied of these with a clear connection already established between the gut microbiome and specific medical conditions.

One of the best known is inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which is a chronic immune-mediated gastrointestinal disease consisting of two subtypes – ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease. According to a 2019 paper by scientists from the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, studies with human subjects demonstrate the gut microbiome differs significantly in patients with IBD versus healthy control subjects.

There is a huge potential addressable market for this, with the US Center for Diseases Control and Prevention estimating that in 2015, 1.3% of US adults (roughly 3 million people) reported having been diagnosed with IBD.

There is a growing interest in developing microbiome-modulating interventions for IBD, from probiotics and prebiotics through antibiotics to faecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and gene manipulation.

FMT, for example, is often employed to treat IBD as well as Clostridioides difficile, a bacterium that causing diarrhoea and inflammation of the colon. In fact, there are some historical records that suggest it was first used in traditional Chinese medicine as early as the III century AD.

The potential stumbling block for growth of the space, however, is the still relative high cost of microbial therapies. For example, according to estimates from a study conducted in Denmark, the weighted average cost of FMT stood at between €2,864 and €3,326 per patient, depending on the method used.

That cost can put FMT out of reach for many, although there are some studies suggesting it is relatively cost-effect when compared with other treatment options for recurrent infection from Clostridioides difficile.

Metabolite treatments and metabolite sensing

Metabolites are an emerging area of human microbiome treatment. A metabolite is a substance made or used when the body breaks down food, drugs or chemicals. Studying the metabolites produced by intestinal microbes can be an early-warning sign of disease, and in some case the metabolites

themselves may cause illness — so therapies that target them can be useful.

However, according to research by the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, “numerous challenges need to be overcome on the path toward using microbial metabolites for therapies.”

Microbial ecosystems are very complex and can change in different circumstances, so they are difficult to map. One emerging technology which could help overcome some of those challenges is metabolite sensing.

Metabolite sensors combine biotechnology with electronics to detect metabolite levels. Today

they are often used to analyse bodily fluids in vitro, but there are an increasing number of non-invasive, wearable metabolite sensors emerging, such as an ear-clip that is able to measure the

glucose levels of diabetic patients from their earlobe tissue.

A 2022 paper by the American Chemical Society examining the variety of bioelectronic devices currently available concluded that: “Overall, we anticipate seeing breakthroughs in organic electronic metabolite sensors thanks to their unique set of features, especially in wearable and implantable forms and at the

interface with in vitro tissues. The exploration of multifunctional semiconductors, unconventional device architectures and systematic study of intrinsic mechanisms will further develop this exciting field.”

Skin deep

Microbiome treatments extends beyond the gut flora. Terms like “skin microbiome” and “lung microbiome” are increasingly circulating in the public space. Researchers from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology have found a positive correlation between gut microbiota at birth and development of asthma and skin eczema later in life. Changes in the microbiome are believed to be

involved in the “atopic march” where patients have a progressive series of ailments – atopic dermatitis, food allergy, allergic rhinitis and finally asthma.

There is some recent evidence of the effectiveness of topical probiotics on skin health, although most recent studies, like this Keio University study, acknowledge that much further exploration is needed.

There is no shortage of examples of products marketed as “skin probiotic cosmetics” today across most of the developed world. Cosmetic and personal care products are subject to more lax oversight by regulators, compared to medicinal drugs.

A recent paper published by MPDI examined the marketing practices of businesses selling such products and concluded: Terms such as probiotics, prebiotics and microbiome were unheard of in cosmetic products a mere twenty years ago. Their use would be encouraging if it coincided with strong scientific research supporting claims and uncovering the mechanisms of action of the strains and material being promoted. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case.”

About half of the companies marked as microbiome-related in the PitchBook dataset we examined seemed to be related to treatments or cosmetics for skin conditions.

Deep breaths

When it comes to the lung microbiome, scientific studies are similarly still in their infancy. One study by the Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute suggested that a connection between gut and lung is due to

potential microbial exchange via the lymph circulation of the Shanghai Veterinary Research Institute.

A 2022 paper on the emerging role of the lung microbiome in lung cancer diagnostics and treatment stated that the microbiome might impact tumour progression and response to therapy, particularly immunotherapy, and might also contribute to the early development of lung cancer.

The authors of the study warned, however, that “studies to date have been small, single centre with significant methodological variation.” And further: “Large, multicentre longitudinal studies

are needed to establish the clinical potential of this exciting field.”

uBiome – the Theranos of microbiome?

Although microbiome tech offers tantalising possibilities, investors would do well to be cautious. Some “bad apples” have already appeared in this field. The highly publicised case of uBiome was, for example, uncannily reminiscent of the Theranos fiasco.

The Silicon Valley-based startup was developing an at-home test kit for human faeces, aiming to enable patients to know about the makeup of their microbiome. It raised $83m in 2019, but in 2021, uBiome’s founders and co-CEOs Zachary Schulz Apte and Jessica Sunshine Richman faced US federal charges for an alleged scheme to defraud health insurance providers and investors. As of 2021, the founders of the company were reported to be FBI fugitives.

There are also recent disappointments for listed microbiome companies. Among the ones that have gone public, US-based Kaleido wound down its business after clinical trials of a microbiome-based treatment for C. difficile infections failed. Finch Therapeutics, also called off its C. difficile treatment trials earlier this year.