Technology is starting to make it possible to understand the complex interactions of the microbiome in more detail.

“In nature, when a plant or animal is taken out of the forest it can cause a ripple effect through the rest of the area – that’s what goes on in your gut,” says Greg McParland, an investment director at the venture arm of nutritional product provider DSM and board member at probiotic supplement producer Sun Genomics.

Advances in gene sequencing technology and computational power are giving researchers and healthcare professionals an increasingly detailed view of how the human microbiome – the trillions of microorganisms that exist on or in the human body – affect our health.

Whole-genome sequencing allows scientists to see rarer types of bacteria in the gut in greater detail, says McParland, and it is opening up new treatment methods for a variety of conditions.

“They’re finding all these less prevalent types of bacteria people thought were insignificant, these low-abundant species we weren’t seeing before,” he says. It’s now possible to study the interactions between different species as well as metabolites, the substances created when the body breaks down food or tissue.

“That’s been a huge change over the last 10 years or so, but it’s shown how complex it is,” McParland adds.

San Diego-based Sun Genomics is one of a crop of startups taking advantage of the growing precision of microbiome research. It raised money from DSM Venturing in January this year and combines whole-genome sequencing with gut composition analysis to personalise each customer’s supplements.

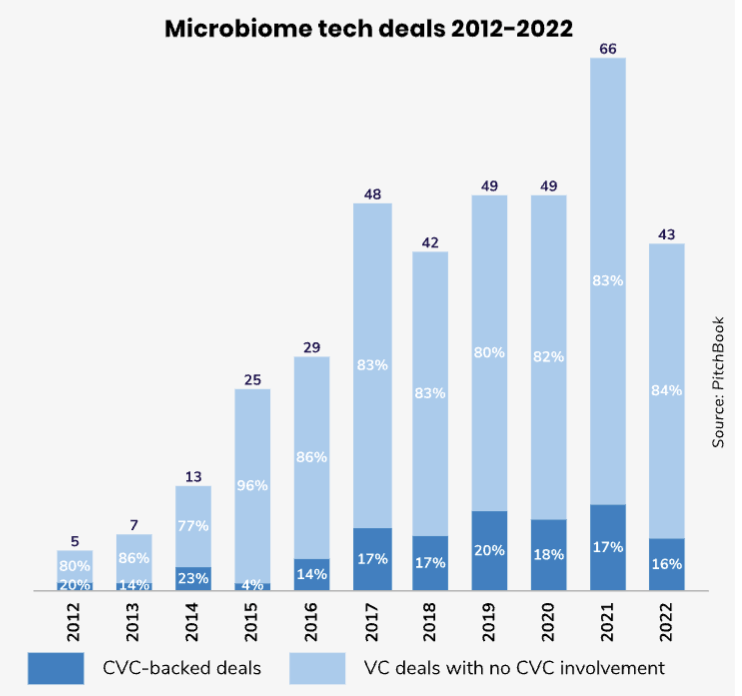

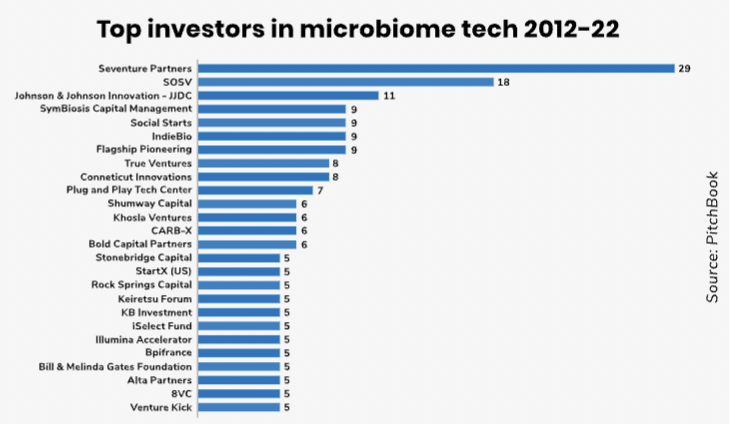

DSM is one of several corporates backing microbiome startups, a group mostly coming from the pharmaceutical industry (Johnson & Johnson, Lundbeck) or fast-moving consumer goods and nutrition (Unilever, Roquette). Studies estimate there are three times as many microbial cells than human cells in the body, yet relatively little was known about their effect before 2007 when the US National Institutes of Health launched the Human Microbiome Project to research how they influence health.

A significant challenge has been the complexity of different microbiomes, and a game changer for research has been the sharp drop in the cost of genome sequencing, which has fallen from over $100m per genome in 2001 to below $1,000 in 2021. Taking things a step further to study not just the microbes themselves but how they interact with each other and with the body requires substantial computational power. But this is now coming, says Owen Lozman, managing director of M Ventures, the corporate venture capital subsidiary of pharmaceutical company Merck.

“In the last five or six years, computation has developed significantly and we have things like quantum computing on the horizon which are going to be able to address these complex multidimensional problems, with generative AI models also helping,” Lozman says.

A year ago, M Ventures invested in Concerto Biosciences, creator of a platform that experimentally measures millions of microbial interactions to gauge how they will actually work as treatments in the overall human body.

“The combination of [advanced computing] with advanced manufacturing technologies, the movement of some chip manufacturing technologies into the biotech industry so that we can enable technologies like Concerto’s have to really produce the science that underpins all of this – I think it all starts to build

the knowledge we need to make this a really interesting field.”

See our profiles of 12 microbiome startups to watch here.

Beyond the gut

Although the gut has traditionally been the focus of microbiome research, several parts of the body have their own microbiome and startups have begun springing up with products targeting them to improve health in new areas.

The skin is home to more than 1,000 species of bacteria and its microbiome is increasingly being used as the basis for cosmetics. DSM-backed Cybele has released a range of serums for eczema and ageing while Straand, a natural hair care startup focusing on the scalp microbiome, recently secured $2m in pre-seed financing from Unilever Ventures.

Another of those areas is oral health. GSK’s Re/Wire Health Studio has backed a startup called Bristle, which offers a microbiome test to inform personalised care by assessing links to conditions like gum inflammation or oral thrush. Evvy has developed a similar test for vaginal care, and both companies are roughly three years old, signifying how the sector is expanding.

The most promising area within the body could potentially be the gut-brain axis, a form of biochemical signaling in which chemicals in the gut can affect the central nervous system. Companies such as Kallyope and Axial Therapeutics are harnessing research and bringing treatments for conditions that include gastrointestinal disease, diabetes and autism spectrum disorder into clinical trials.

“I think there will be some progress in cosmetics, some in pharma and a little bit back and forth,” says Sarah Luppino, an M Ventures investor who sits on Concerto’s board of directors.

“It doesn’t have to be ‘take this microbe and that’s your medicine’, it can also be ‘pair this medicine you always take with this microbe or a metabolite product from a (microbial) consortia you realise is super powerful’. It can roll out in different waves and different flavours over time.”

So far, however, few companies have had microbiome drug candidates get through the clinic, and the ones that have listed on the public markets have met mixed fortunes.

Next steps

Getting detailed data is important but the next stage will require it to be analysed in greater detail, says Artem Khlebnikov, director of bioeconomy, food and nutrition for Eagle Genomics, a company that structures and contextualises microbiome data.

The current state of play is like knowing the alphabet and being able to put syllables together without knowing how to read, he says.

And while the gut-brain axis and gut-skin axis are hot research areas right now, understanding the human microbiome could have an impact on the planet, Klebnikov adds.

If we can get our gut microbiome to break down food so we get the right balance of fats, sugars and proteins in our diet, it could lead to more nutritious plants which need less land, in turn leading to less deforestation. In the future, microbiome projects could even be in line for carbon credits.

“My kids are millennials, and they ask me about the microbiome all the time,” McParland says. “I tell them: ‘Your generation and your kids are really going to benefit from this research’. “That doesn’t mean it isn’t helping people today, but it’s a journey of many, many years we’re on.”