Campus Plus CEO Nick McNaughton looks at overseas programmes for early-stage innovation to understand how Australia could improve its own offering.

In mid-2022 Australia had a change of government: Labour took the reins after 11 years in opposition. The new government has put the commercialisation of science at the very core of the evolution of the Australian economy. On November 30, 2022, the Australian government announced the establishment of a A$15bn National Reconstruction Fund (NRF).

The NRF was established to provide finance for projects that diversify and transform Australia’s industry and economy. The NRF aims to do so via targeted investments in seven priority areas, including but not limited to: renewables and low emissions technologies; medical science; agriculture; natural resources; and defence.

Australian researchers are recognised globally for their excellence in new knowledge creation, ranking highly in both research impact (#9 in citations) and research output (#6 in publications per capita).

Research impact has started translating into commercial success. In 2021, commercialisation activities yielded an aggregate of around A$1.8bn through a combination of commercialisation revenue (A$251m), industry research contracts (A$800m) and equity raised for spinouts (A$726m).

With research expenditure in 2021 being A$11.9bn, this translates into a return on research capital (RORC) of 15.1% — higher than both the US and China, both around 6%. This validates that Australian research has a tremendous commercial impact and justifies more investment in research commercialisation.

Limited tech transfer resources in Australia

The problem is Australia languishes in 91st place on the Harvard University index of economic complexity. The government wants to finally crack the nut of turning science into jobs. The key to achieving this is to invest in and support greater technology transfer capability.

Currently, technology transfer offices remain understaffed, with only 237 personnel hired to commercialise the intellectual property developed by 38,717 research staff employed by Australian universities. Resource imbalance is also a concern with two-thirds of technology transfer professionals employed by a Group of Eight institution — the remaining universities have, on average, less than two technology translation officers per institution.

The lack of resources makes it difficult for universities to invest in critical value creation and value extraction initiatives for research commercialisation, such as:

- Providing education to research staff on the importance of intellectual property (IP), and processes for commercialising IP;

- Providing early research commercialisation funding for prototyping, lab trials, developing proof of concepts and pilots with industry;

- Grant funding for spinouts (where appropriate) or resources for joint developments, research contracts and joint ventures.

There are several reasons that universities, particularly those not in the Group of Eight, have not invested enough resources into their TTOs:

- The meritocracy of the university system rewards publications, citations and grant funding. The system penalises a researcher, research team, school and faculty if they divert time to commercialisation activities.

- Lack of top-line income or capital on the balance sheet to establish or fund a TTO;

- Lack of successful case studies from the institution to justify establishing or funding a TTO;

- Lack of knowledge and/or relevant experience in senior leadership to correctly establish and structure a TTO;

- For universities located in non-urban locations, difficulty finding TTO talent willing to relocate to rural or regional townships.

International models: KiwiNet and HEIF

In New Zealand, the government saw the same problem. They fixed this through the establishment of KiwiNet. It is an alliance of 19 research organisations working towards one common goal: transforming scientific discoveries into new businesses, for all. This approach has provided numerous benefits to their economy. It has increased alliances and partnerships; upskilled the sector; increased capability and provided a streamlined and frictionless commercialisation process. In 2022 they scaled the pipeline to more than 830 projects, launched 35 startups and created NZ$255m in financial returns for New Zealand.

This underinvestment in technology transfer is difficult to comprehend, given that the return on investment of technology translation, when done properly, is so high.

In the UK they have Higher Education Innovation Funding (HEIF). This programme supports knowledge exchange between higher education providers and the wider world that benefits society and the economy. It is a £260m programme (over five years), the aim of which is to create and sustain a range of knowledge exchange activities in response to demand across the economy and society. It is designed to support and develop a broad range of knowledge-based interactions between higher education providers and the wider world, which results in economic and societal benefits to the UK.

As an example, several universities use the programme to fund additional tech transfer and commercialisation staff. University of Leeds has 15 commercialisation staff; 12 are funded by HEIF. This allows the institution to build capacity and capability in its research commercialisation offices.

It has been proven in the UK that HEIF provides a strong return on investment, with £8.30 generated for every £1 of funding.

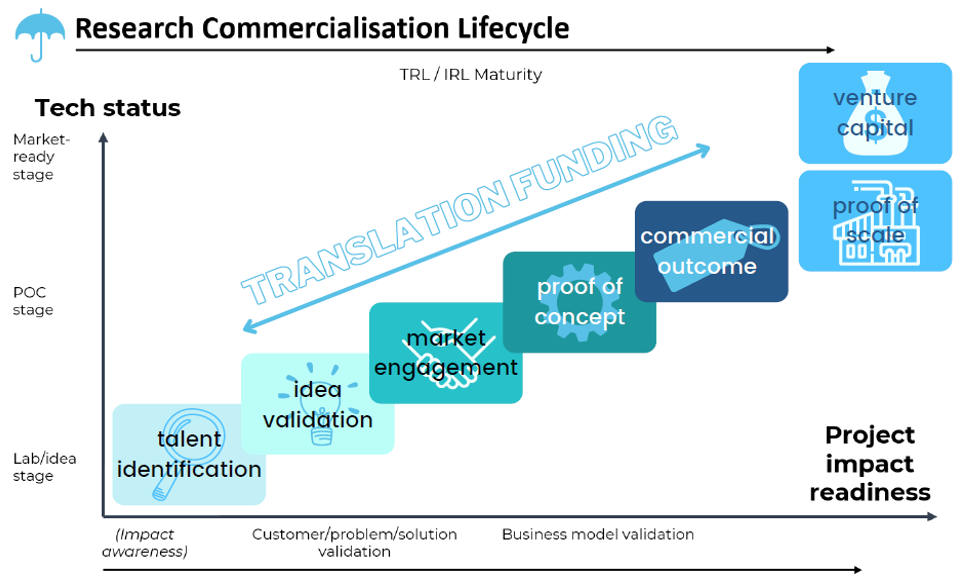

When you consider the research commercialisation lifecycle (see chart below) we also see the importance of translational funding.

Australia’s focus on life sciences leaves other sectors behind

Australia is also lacking a National Translation Fund. There is significant support for the translation of health and medtech ideas (such as the Biomedical Translation Fund, Clinical Translation and Commercialisation Medtech, Medical Research Commercialisation Fund and Medical Research Future Fund) but support outside this sector is lacking.

Translation funding is needed to establish if an idea, discovery, or invention has commercial application. There are examples of the return-on-investment benefits from translational funding.

Other nations have invested in comparable ‘National Translation Funds’ – centrally administered, government-backed exploratory funds distributed to research projects ready for commercialisation.

The Singaporean approach: Start-up SG Tech

The Start-up SG Tech grant fast-tracks the development of proprietary technology solutions and catalyses the growth of startups based on proprietary technology and a scalable business model. Start-up SG Tech is a competitive grant that supports proof-of-concept (PoC) and proof-of-value (PoV) for the commercialisation of innovative technologies. Companies may apply for PoC or PoV grants depending on the stage of development of the technology/concept.

- PoC grant: up to SG$250,000

- PoV grant: up to SG$500,000

The Start-up SG Tech grant replaced the previous Technology Enterprise Commercialisation Scheme (TECS), through which $95m was distributed to Singaporean researchers.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) carried out an estimate of economic return from this initiative and calculated those startups funded through these programmes contributed $800m towards Singaporean GDP, a return-on-investment of 8.42x. Start-up SG Tech programmes have been built on the learnings gained from TECS and are expected to achieve a superior outcome for Singapore. Singaporean spinouts built from research carried out at a Singaporean university or public research institute (i.e. A*Star) are eligible.

Building on Horizon: the ERC Proof of Concept Grant

Frontier research often generates radically new ideas that drive innovation and business inventiveness and tackle societal challenges. The European Research Council (ERC) PoC Grants aim at facilitating the exploration of the commercial and social innovation potential of ERC-funded research and are therefore available only to PIs whose proposals draw substantially on their ERC-funded research. The PoC grant is up to €150,000.

The PoC grant is built on the findings from the €80bn Horizon 2020 Program, which ran from 2014 to 2020. The European Commission estimates that the Horizon 2020 Programme has contributed €400bn to €600bn towards GDP, a return on investment of approximately 6.25x.

Campus Plus has successfully managed research translation funding on behalf of several Australian universities for over 10 years. The Campus Plus Discovery Translation Fund (DTF) has disbursed $5m in commercialisation grants to over 100 research projects. Projects funded through DTF have gone on to raise $50m in spinout funding — a return on investment of $10 per $1 spent (a report is available on request).

Australia also needs to systemise and programise its talent identification and researcher development programmes. Currently, these are ad hoc, distributed and underfunded.

Over the last five years, the country has benefitted from the CSIRO On-Prime programme (and others like it). On-Prime is a free programme designed to help research teams of two to five people take their projects to the next level through customer discovery activities and more. The facilitators work with researchers at any stage of their project across all disciplines. During the nine weeks of On Prime, researchers develop a deeper understanding of the people who could benefit the most from their research and sharpen their skills to communicate with that audience. Expert facilitators support the researchers to build evidence for the impact of their research, so they can make a difference in the world and attract the resources they need along the way.

The UK has a similar, more developed programme: Innovation-to-Commercialisation of University Research (ICURe) is the country’s leading early-stage research accelerator programme. It guides academic researchers through the process of refining and validating the commercial potential for some of the world’s leading-edge science, technology and knowledge assets. The programme has been funded by Innovate UK and since 2013 has helped create over 150 new companies by supporting more than 1,650 participants to explore the commercial potential of their research. ICURe has created more than 500 new jobs and led to additional funding of more than £250m raised.

Tax incentives for investment in high-risk research-intensive businesses

There is a need for an investment scheme that provides incentives (tax breaks) for individuals to invest in risky, early-stage ventures. The UK has two such schemes:

- The Enterprise Investment Scheme (EIS), and

- The Seed Enterprise Investment Scheme (SEIS).

EIS is designed so that a company can raise money to help grow its business. It does this by offering tax relief to individual investors who buy new shares in the company. Under EIS, a company can raise up to £5m each year, and a maximum of £12m in its lifetime.

First introduced in 1994 with the goal of stimulating the growth of the UK’s innovative SME sector, since then the EIS has gone on to support an incredible 36,720 early-stage businesses, raising over £25bn of investment during that period.

SEIS is similar, but specifically designed to help companies raise money when they’re starting to trade. A company can receive a maximum of £150,000 through SEIS investments. A total of £1.4bn has been placed in companies since the launch of the SEIS scheme in 2014.

Nick McNaughton is the founder and CEO of Campus Plus, a global specialist in the commercialisation of research. You can contact him via email, LinkedIn or phone.

Campus Plus is headquartered in Australia, with a goal to build a system that, by 2025, creates thousands of new high-tech jobs a year. We specialise on delivering local solutions to global problems based on breakthrough research.

Campus Plus has grown significantly since starting three years ago. We currently provide outsourced technology transfer services — ranging from early education through to technology transfer, licensing and venture funding — to 23 Australian universities. Over 3,000 researchers have participated in our research commercialisation programs, with 100 research teams receiving translation funding managed by Campus Plus on behalf of our university clients. Campus Plus now has a network of consultants across all National Priority Areas distributed all over the country.

Most recently, Campus Plus was selected through a competitive tender process to manage the National Industry PhD Program, on behalf of the Department of Education. The National Industry PhD Program will train over 1,300 PhD scholars in industry-research engagement, deepening links between industry and the research community.