Startups creating defence technologies like drones, AI and hypersonics are in demand. But can they work well with big defence contractors?

Raytheon Technologies, one of the world’s largest defence contractors, launched a corporate venturing unit early last year at a critical time for the defence industry. Not only are geopolitical tensions rising again, but the rules of military advantage are changing — what was once a race for nuclear arms and spaceflight is now chasing microchips, artificial intelligence, hypersonics and advanced automation.

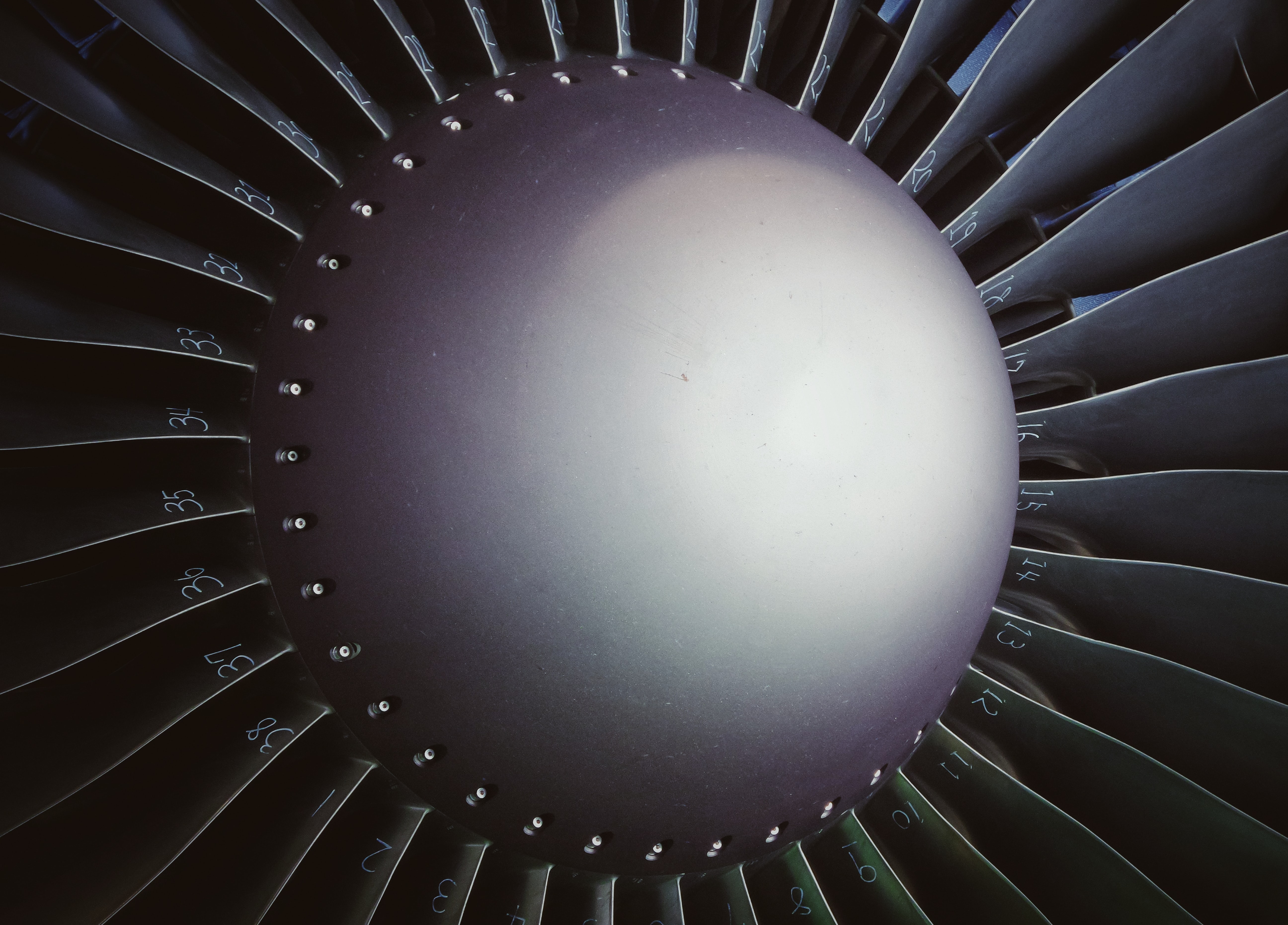

The US – the world’s premier military power for the better part of the past century – is straining to stay ahead of the technological curve, and its defence industry has been revving up its innovation engines to help it do that.

“The war in Ukraine is demonstrating a lot of early-stage technologies being deployed, including satellite technologies, imaging from space, drones, advanced communications – pulling these communications together – from multiple platforms,” says Dan Ateya, president and managing director of RTX Ventures, the Raytheon Technologies investment arm.

“There’s even aspects of advanced propulsion and some of the things that Russia’s supposedly done. So I think this is really highlighting to a community that over the last 10 to 12 years has been growing in terms of investment interest.” Ateya told GCV’s Global Venturing Review podcast about his plan in a recent episode.

This was the first time Raytheon had established an arm to invest in startups, but in the year since the creation of RTX ventures, the company has been moving fast. It has invested in eight startups so far, including a recent deal to back EpiSci, the defence automation company.

“We’re off to the races,” says Ateya. “We’re already seeing a lot of engagement between different parts of the businesses and these external startups.”

Ateya, who has a PhD in mechanical engineering and whose career includes a stint at the Naval Research Laboratory and more recently as director at 3M’s CVC unit – joined Raytheon, a US aerospace and defence company, in February 2022 to helm the new unit.

“The company had a really good forward-looking vision of how to set up a group like this. What’s really pleasantly surprising to me is, for a large company they’re really interested in supporting the startups that we’re putting into our portfolio,” says Ateya.

“There’s a real, clear interest to build this innovation ecosystem and to try to use our resources as a company to support these startup companies.”

As CVCs’ share of venture deals has continued to increase over the years, there was a feeling in Raytheon that this was a new tool that can be used to complement its existing innovation capabilities and R&D. It probably also helped that a number of the corporate’s peers in aerospace and defence – such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing and BAE Systems – had been actively investing in startups for some time.

“In the first year, we had to establish a base of processes, internal and external communications, build our initial portfolio, and I think all of that has gone very well. Now we get into a new phase of helping manage the portfolio successfully, helping optimise engagement between the portfolio and some of our businesses where it makes sense, and continuing the process of sourcing new deals,” says Ateya.

Future weapons

Like any big defence contractor, Raytheon already has a robust R&D and innovation function that the CVC is complementing, and regular touchpoints are set up with them and with the CTO’s office, according to Ateya, to align strategy and technical priorities, and monitor customer interest in particular areas.

Helpfully, the US government has its own ideas about the areas that need attention. The White House put out a list in early 2022 of 19 critical and emerging technologies that the country will need for national defence. The list includes hypersonics, advanced computing, artificial intelligence, biotechnologies, quantum, advanced nuclear energy, advanced engineering materials, semiconductors and space technologies.

“It’s a great list and frankly, what we’re looking at RTX Ventures aligns nearly a hundred percent with the technologies listed in there,” says Ateya.

To the extent that certain industries are subject to changing political winds, one might think that an area as politically sensitive as national defence would be that much more so. In the US, however, where national security spending has always more or less enjoyed bipartisan support, there is not a sense that technological priorities will change along with new administrations.

“I think it’s very insulated. These are obvious areas of technology development, there’s global competition for these. Some of our perceived adversaries are making a lot of progress in these areas,” he says.

“I would imagine over time the list may morph and shift, but the core is going to be the same for years to come.”

Indeed, there is a lot of overlap with the themes that pop up when leafing through the CVC’s portfolio, which boasts startups such as hypersonic aircraft developer Hermeus Corporation, electric propulsion companies H55 and Verdego, as well as EpiSci.

The unit is flexible in terms of investment stage – having invested as early as seed and as late as series E so far – largely because what is considered early or late-stage varies widely depending on the kind of technology involved. Hardware-heavy projects tend to be more capital intensive with longer lead times and more fundraising on the horizon, meaning that a series E is not as late as it would be with a software startup.

Shepherding fledglings

The real challenge comes in getting the technology to market. With the main customers being the government – mainly the Department of Defense in the US – the path to securing a contract is a labyrinthine one, known as the “Valley of Death” by industry insiders. Many startups don’t make it out.

“There’s a lot of programmes to get initial funding for startups. How many of them really get the programme of record or the large scalable production contract at the end of the rainbow? That’s a big issue in this space,” says Ateya.

A company as embedded in the industry as Raytheon, though, tends to know where to find latent demand for what a startup is selling.

“We’re able to identify where in the government we should maybe go to with a startup company to try to get the right traction and understanding of market interest. In our first year, we’ve been very active to try to leverage some of these strengths as an organisation, and I think we have some good success stories in a short period of time,” he says.

Not just military

Half of Raytheon’s business is in the commercial sector, and for RTX Venture’s startups, a commercial function can provide an alternate and more flexible route to market.

“There is a lot of overlap with technologies, especially when you get to aspects of AI and ML and advanced communications, micro-electronics and semiconductor technologies. There’s a lot of application across both worlds.”

For startups that are more national security or military-oriented, though, a big part of an investor’s due diligence is looking at how well they can protect their information, given the heightened sensitivity of potential customers. Companies also have the additional hurdle of needing the right clearances to work with the government.

“It is a sticking point because it’s hard for startups to even get really good end-customer feedback if they don’t have the appropriate clearances,” says Ateya. “It’s a chicken or egg problem that is unique to this space and we’re watching startups deal with it.”

Fernando Moncada Rivera

Fernando Moncada Rivera is a reporter at Global Corporate Venturing and also host of the CVC Unplugged podcast.