Having a corporate investor decreases the chance of a startup going bankrupt and increases valuation relative to EBITDA if there is an exit.

Having a corporate investor halves the chance of a startup going bust and increases the exit multiple the business will get when it is acquired or floats on the stock exchange. These are the conclusions we drew from a recent analysis we carried out at Global Corporate Venturing, looking at a global cohort of startups in the 10-year period between 2013 and 2023, leveraging PitchBook´s data.

Corporate investment is becoming an increasingly prominent part of the mix of funding options for startups, with around 19% of startup funding rounds globally now including a corporate investor.

These CVC investors often say they have very specific benefits they can offer startups. For example, they can provide practical business assistance, from testing lab access to distribution channels and introductions to potential customers.

Stephanie Downs, founder of Uncaged Innovations, a startup creating plant-based leather from grain protein, recently took investment from Jaguar LandRover’s investment arm, Inmotion Ventures, and says she has been pleasantly surprised by how helpful the carmaker has been in introducing them to other potential customers. Downs is in talks with another potential investor, a manufacturing company, which could help get the plant-based leather into production.

“Having a manufacturing company that could advise on this would be like suddenly having a manufacturing department without having to spend any money on building one,” Downs says.

Despite many such anecdotes, however, it has been unclear if this kind of involvement really translates to material differences in outcomes for startups backed by corporations. So, we took a look at the statistics and found that it does appear to, with the most noticeable impact being on a startup’s ability to avoid bankruptcy.

We examined PitchBook´s data between 2013 and June 2023, encompassing all VC transactions across the globe during the period. All companies were split into two major groups. The first group included those that had raised at least one round backed by at least one corporate investor since inception and had raised a minimum of two VC rounds since 2012. The other group included companies that had not received any corporate backing in any round ever but had raised at least two rounds since 2012.

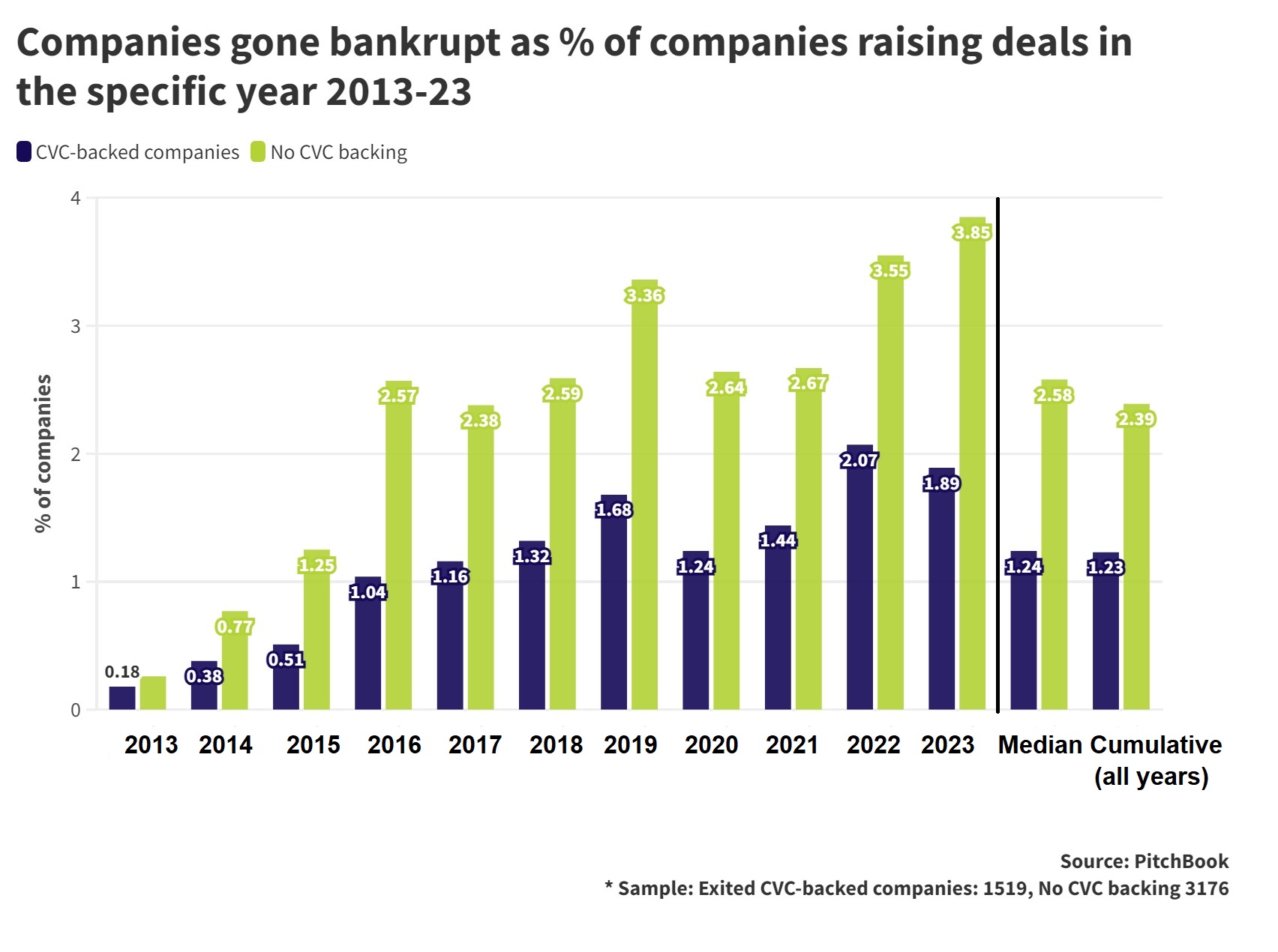

Looking at how many of those companies had gone bankrupt, we noticed a marked difference between the two groups. Of all the companies that have gone bankrupt, those that had no corporate backers are roughly twice the number of the corporate-backed ones that have gone bust. This is true for almost every year in the analysed dataset. It is also true on a median and cumulative basis. A company without a corporate backer appears two times more likely to go belly up than a company that has had at least one such investor on its cap table.

It is worth noting that bankruptcy rates in general need to be treated with some caution. Companies do not always announce these proactively, so they can be sometimes be slow to be picked up by database compilers like Pitchbook. But, even if startup bankruptcy figures may be somewhat underreported, that same tendency is true for both of our datasets and would not affect the overall comparison.

There are several potential reasons that corporate-backed companies have higher survival rates.

One theory is that corporate investors may have better due diligence, especially when it comes to more technical companies. This is one of the reasons that investment company Foresight has partnered with WAE, formerly Williams Advanced Engineering, the engineering consultancy that was spun out of Williams F1, for its deeptech investments.

“It’s that engineering expertise that gives us the confidence to invest in early-stage hardware companies because we can tap into their expertise for hiring the right technical team, their understanding of the challenges of bringing a hardware product market, their understanding of the IP strategy,” says Andy Bloxam, managing director of the Foresight Venture Capital team.

In addition, simply being backed by a corporation helps validate a startup, which can make it easier to raise further funding.

“Many investors take comfort from the idea of a strategically aligned corporate, which understands the market, being invested. I think that can help pull rounds together, the perception of that knowledge. And I’m sure that that would feed into the rates of survival,” says Bloxam.

We repeatedly hear this from startups. Paul Drysch, chief executive and co-founder of PreAct Technologies, a lidar technology startup, says the company started to see more traction from other corporates, after attracting insurer State Farm as an investor.

“Having a company like State Farm invest in you and work with you provides a way into the market whilst providing additional credibility. Once State Farm showed interest, it almost incentivised other insurance companies to want to knock on the door and talk with us,” he said in an interview with GCV earlier this year.

“A CVC investor is seen as a validation of market demand,” agrees Downs. “That validation is something that other investors always ask about.”

Higher valuations on exit

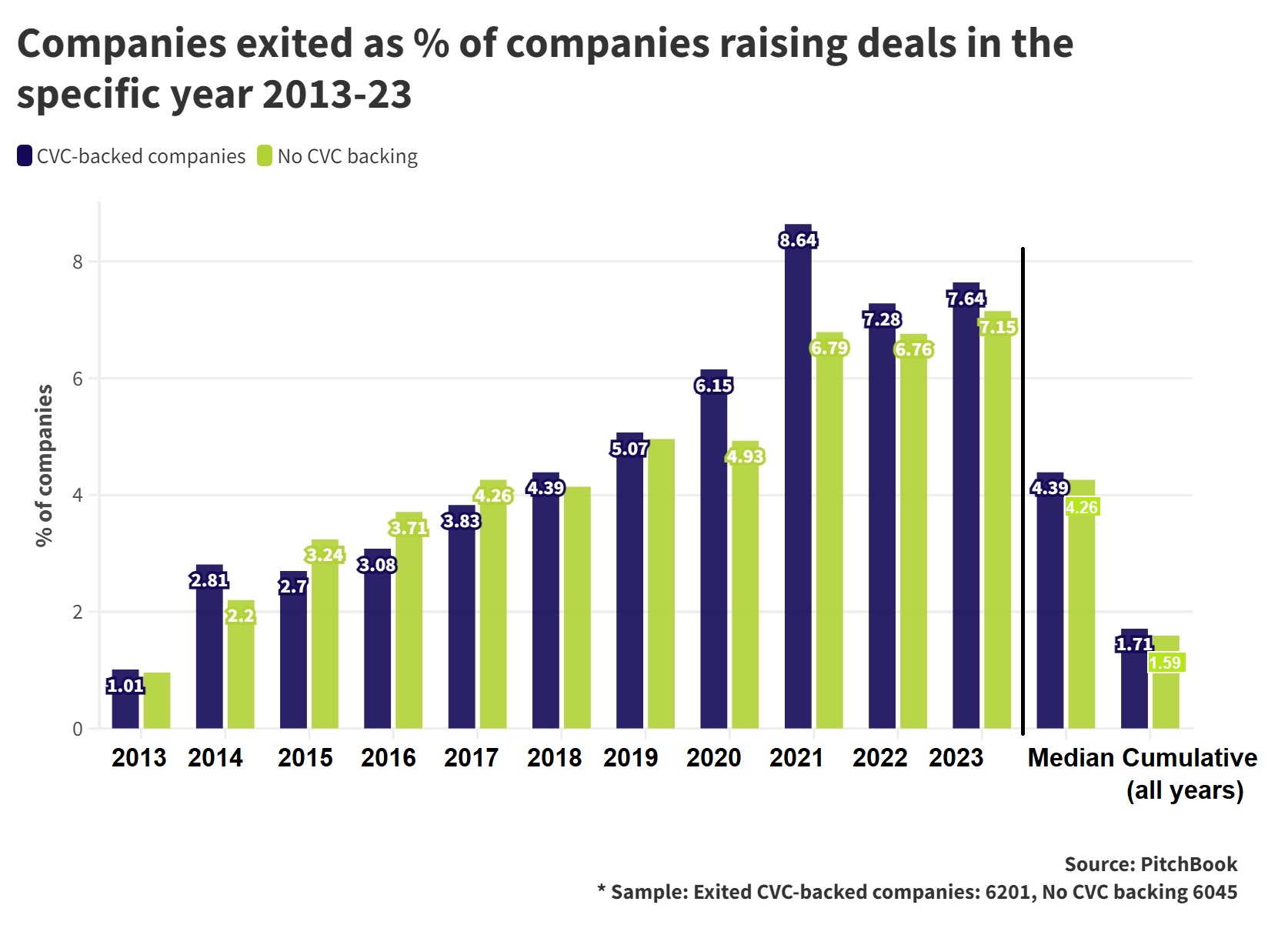

We found that corporate backing made very little difference to whether a startup was acquired or listed on the public market. The median percentage of corporate-backed companies out of the total of all companies that raised a round in a given year (4.39%) is only marginally higher than that of companies without corporate backing (4.26%). Corporate backing or not, one in about 25 portfolio companies is likely to score an exit in any given year.

It is worth noting that, on a cumulative basis, exit rates are much lower for both cohorts – 1.71% of corporate-backed ones versus 1.59% for the rest. The lower cumulative figure reflects the fact that some years see much lower exit rates than others. But, whichever number we use — median or cumulative — the conclusion remains the same: the corporate-backed cohort is only slightly more likely to score a exit than the rest.

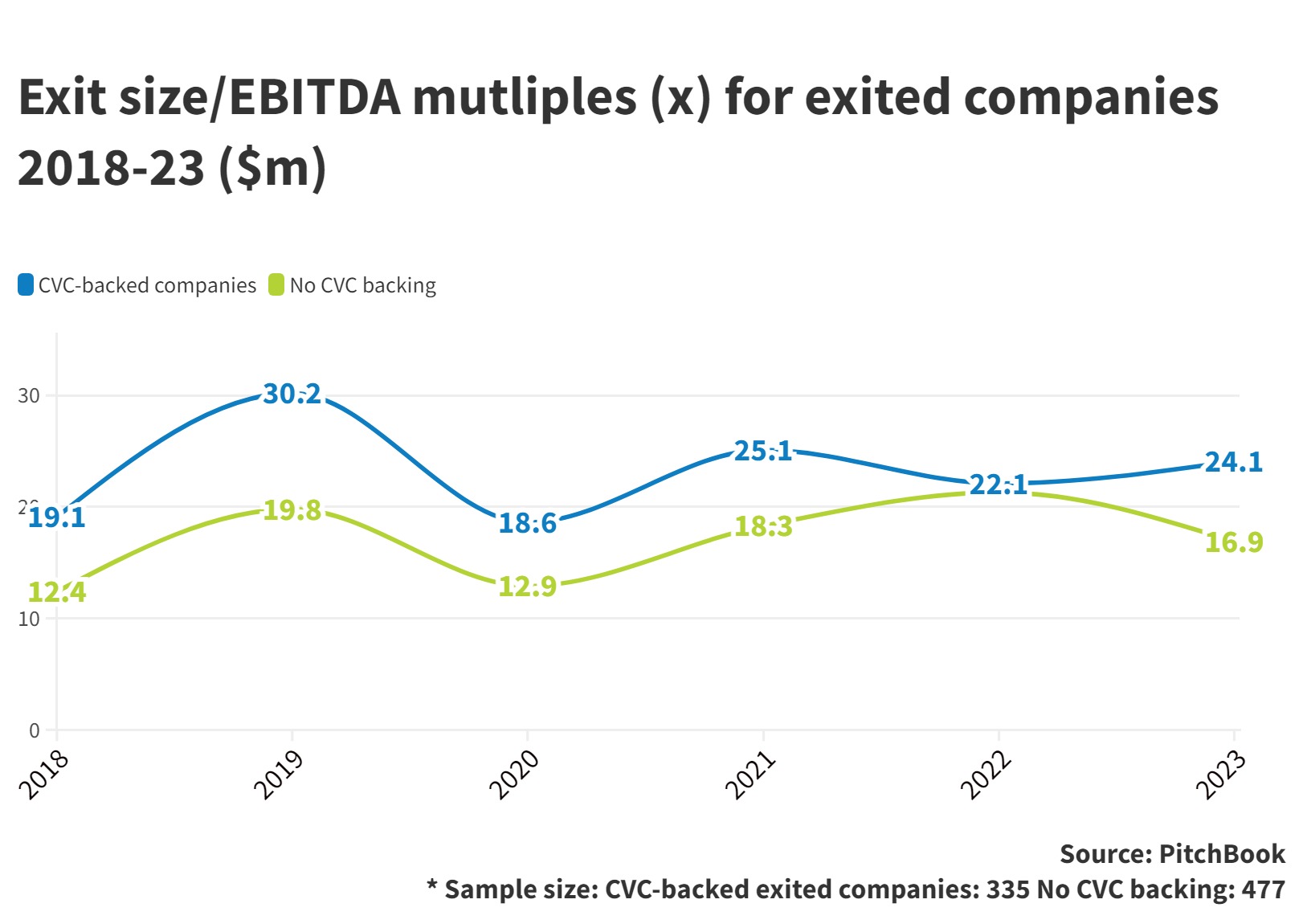

Where corporate-backed companies do seem to have a considerable advantage, though, is acquisition multiples. We looked at the ratio of deal value to the startup’s earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) and found that from 2018 onward this has been higher for corporate-backed companies than for those without one. The only exception was 2022 when multiples were the same for both groups. Each of the years analysed contains at least 30 instances for each cohort where both the exit size and the EBITDA of the acquired company are known.

Are these companies achieving higher valuations because corporate investors are stepping in to acquire the startups — and perhaps overpaying in the process? Corporate investors do have a reputation for overpaying on deals, says Wim Ponnet, founder and CEO of sports, media and entertainment company FanTechCap, who was previously chief strategy officer and chief commercial director at Endemol Shine Group. He has been on both sides of the corporate-startup divide in a career that also includes Yahoo and Coca-Cola.

“I think the reality is that you very often overpay for things,” he says. “In my corporate role I have done that.”

But not all of these valuations can be the result of an overgenerous corporate investor-turned-buyer. While potential acquisitions can be one of the reasons that corporations engage with startups, corporates buy the businesses they have minority stakes in much less frequently than people might think. In our most recent survey of corporate venture units, a majority —57%— reported that none of their portfolio companies had been acquired by the corporate parent.

Higher exit multiples may be the result of a number of factors. One could be the willingness to be patient. Babur Ozden, whose digital knowledge platform company Maana was backed by Aramco, Chevron, Conoco, GE, Intel and Shell, says corporate investors often allow startups more time to grow and establish themselves before going for a sale. Ozden sold Maana in 2021, nearly a decade after it was founded.

“Return on investment for a CVC is multi-dimensional. In addition to a desirable financial exit, the other two ROI dimensions are use of portfolio company’s tech by the parent company and adoption of portfolio company’s tech within the industry the parent company operates. ROI not being measured solely by the size of the financial exit, enables CVCs to nurture [portfolio companies] more firmly albeit may be slowly.”

Corporate investment is not by any means always perfect or smooth. One of its biggest failings is that CVC units can end up being somewhat inconsistent investors as the teams can be subject to changing priorities at the parent corporation.

“They can be very dependent on the overall strategic direction of the parent company, which can change, particularly in downturns. What was strategically important two years ago when the corporate led the series A round can change so that it no longer wants to follow [in the next fundraising round],” says Bloxam.

“If it’s non-core to the business, the startup can sit there like an orphan,” agrees Ponnet.

Startups are also sometimes concerned that a corporation writing a large cheque may seek to have too much influence over them. Not every startup-corporate relationship is successful.

But the data would suggest that having a corporate backer does, ever so slightly, improve the odds of a startup doing well.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).