March 2022 editorial by James Mawson, editor-in-chief, Global Corporate Venturing

Sam Altman, chief executive of artificial intelligence-focused foundation OpenAI and former head of Y Combinator accelerator, reminded people last month of the main early-stage investing questions:

- Of all the things you could work on, why this?

- How does this eventually become a $100bn business?

- What do you understand about this that others do not?

- What progress have you made in the last week?

- What are you really great at?

Good questions for a startup. But they are also good ones for the corporate venturing industry to reflect on.

Global Corporate Venturing has tracked more than 6,000 corporations over the past dozen years investing directly in startups. Most, however, struggle to stay the course.

Ilya Strebulaev, a professor of finance at Stanford Graduate School of Business, with student Amanda Wang (see their guest comment, page 54), found more than 60% of the senior executives they spoke with confided that their parent companies do not understand the norms of corporate venture capital (CVC).

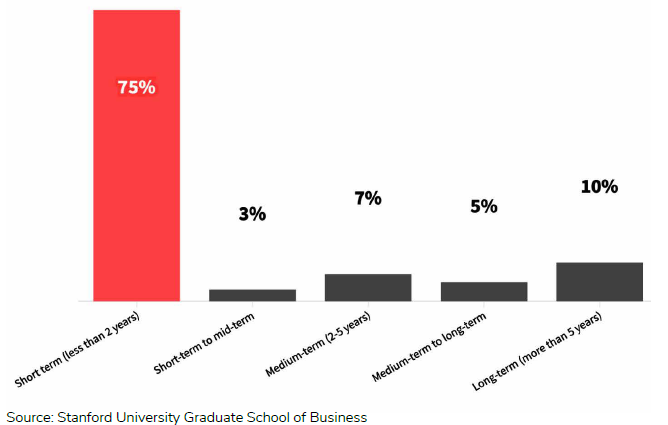

One of the most crucial of which in their broader paper was 75% of their 74 US-based CVC interviewees said the evaluation horizon for their CVC unit was less than two years. And just 10% said their evaluation horizon was five years or longer.

This points to the common inflection points in the CVC journey used by the GCV Institute to help programmes prepare for likely issues that affect them at two to three years, that is how to survive, and then expansion and resilience after six to seven years have passed.

Given most exits happen on average at about a decade after investment and it is clear why the Institute is as heavily in demand by the corporate parents to help them understand how to land the value of corporate venturing and manage the innovation tool as it is within CVC units themselves.

But too many corporations are still thinking too small about the power of CVC. A traditional corporation will think a business unit meaningful only when it has hundreds of millions of dollars or billions in revenues. CVC units, however, usually barely scratch this range.

After more than a decade running credit card company American Express’s CVC unit, Amex Ventures, Harshul Sanghi now manages more than $1.2bn (see people news on page 16) at the time of retirement at the end of March.

The value of his portfolio companies runs into the tens of billions and Sanghi has been a consistent member of the GCV Powerlist 100 throughout his tenure as a leader of the CVC society.

But there are indications of greater ambition among CVCs to reach the $100bn of assets, achieved by SoftBank with its Vision Funds, Tencent, Prosus and Alphabet among others. These groups invest billions and reap the strategic impact as well as stellar financial returns.

But corporations are more than just direct investors in startups and hence immediate customers and suppliers to them. Crucially, they help the ecosystem more indirectly as limited partners (LP) of venture capital funds, especially debut ones.

GCV’s publishing company, Mawsonia, is a strategic LP of debut VC funds founded by experienced, strategic investors, such as Black Opal Ventures, and looks to add value beyond the commitment by focusing on bringing in additional dealflow and commitments and talent to help them expand rapidly.

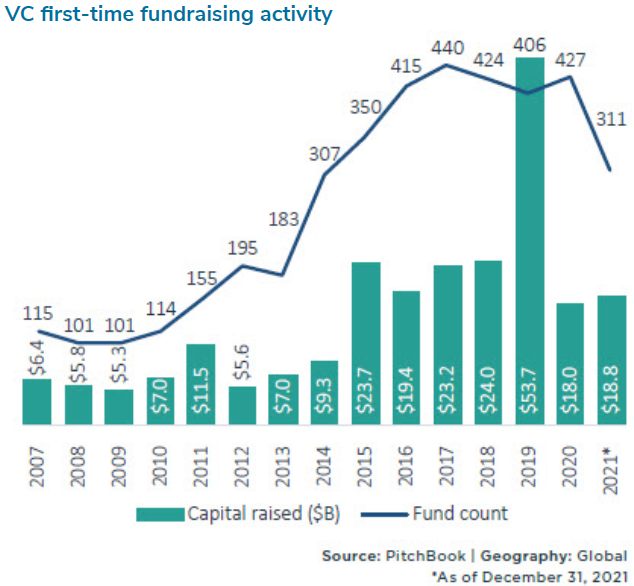

This is crucial at a time when the number of debut VC funds fell by a quarter last year compared with 2020 or more against the peak.

Last year, 311 first-time VC funds raised $18.8bn, down two-thirds or more compared with the pre-pandemic value high, according to data provider PitchBook’s 2021 Annual Private Fund Strategies Report.

As Jon Gordon, former managing director of Commonwealth Care Alliance’s (CCA) venture investment subsidiary, Winter Street Ventures, said about his new VC firm, HC9 Ventures, it was “an interesting hybrid – it is actually all strategic individuals (healthcare executives and entrepreneurs) rather than organisations”.

“This allows us to work with competing entities without having to choose favourites.”

But sometimes people have to choose. Missing from Altman’s list of questions is who do you want to work for and with?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the end of February came eight years after taking Crimea and the Netherlands government has been taking Russia to the European Court of Human Rights for its “role in the downing” of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 that same year.

GCV took stock then and advice from our Dutch friends and customers was to retain Russia-based CVCs as part of the community.

The mood has hardened with the latest invasion and unanimous feedback has been given to GCV to bar them going forward.

The mood is also hardening with other countries.

Hunter Lewis, founder of Cambridge Associates, an adviser on alternatives, wrote in the Wall Street Journal last month: “Another ethical challenge for US venture funds arises from their growing and profitable ties to China. The Journal has reported that the industry is funding Chinese semiconductor and other high-tech industries that support the Chinese military at a time when China is testing hypersonic missiles designed to thwart US missile defences. Some US tech companies, including semiconductor companies, appear to be doing the same.”

Last month’s GCV delved into the capital flows between the five main venture markets: Japan, US, China, India and UK and published a series of academic papers on US and China ties ahead of a series of presentations at the GCV Symposium in mid-May.

If Sebastian Mallaby is right in his new book, Power Law, VCs have emerged as a “third great institution of modern capitalism”, combining the organisational strengths of companies with the flexibility of markets, as per Economist’s review, then it is helpful to know where the money is flowing.

Bob Ackerman, managing partner at VC firm AllegisCyber Capital, said: “Research that I have seen shows that almost 40 Silicon Valley venture firms have money not just from China, but money that can be traced back to the CCP/PLA [Chinese Communist Party/People’s Liberation Army].”

Five years ago, this column argued that with “Europe fracturing under divergent member state aims and Russian pressure, and Asia grappling with China’s crackdown under President Xi, a panglossian degree of optimism is unwarranted about the economy or much else”.

From trying to bring capitalism and democratic norms to other countries 20 years ago, the world has taken a darker turn.

Experienced entrepreneurs, such as Scott White, chief executive of chips startup Pragmatic, at our CVC delegation to University of Cambridge before last year’s GCV Symposium, are increasingly thoughtful that focus on rapid growth alone is not enough and long-term relationships can limit which investors to take money from.

These insights helped underpin our latest book, Transformative Innovation, co-authored with Christine Gulbranson, which looks at the implications for countries and individuals as well as corporations and universities of strengthening the main economic institutions underpinning Leviathan.