Analysis by James Mawson, founder, Global Corporate Venturing and co-author of Transformative Innovation (with Christine Gulbranson)

Elon Musk, founder of Tesla and SpaceX, said: “Technology leadership is not defined by patents, which history has repeatedly shown to be small protection indeed against a determined competitor, but rather by the ability of a company to attract and motivate the world’s most talented engineers.”

Analysing why China-based corporate venturing units – those taking minority equity stakes in private third-parties either directly or as limited partners in venture capital (VC) funds that then do so – had been so quick to develop their activities, Jeffrey Li, managing partner at Tencent, said: “The competitive landscape of China internet space, especially the very high iteration speed of the market, forced all major players to capture future innovation.

“In that case, there might be relatively more minority deals [in China] compared with the US market. And the giants might leverage their market resource to speed up the growth of the investee company.”

As a result, China-listed Tencent invests almost all its free cashflow on CVC, according to Jeffrey Li in a keynote at the GCV Symposium before the pandemic hit.

Now, Silicon Valley firms, such as Andreessen Horowitz, recognise that whereas a decade ago California was probably 10 times faster in its pace of innovation than anywhere else in the US (and hence world) now China is 10 times faster than the Valley, according to Mach 49.

So venture capital becomes strategic for economies as well as corporations and individuals and hence more capital has flown in as returns become clearer. As The Economist said: “America’s VC funds have seeded firms that are today worth at least $18trn of the total public market. Seven of the world’s 10 largest firms were VC-backed.”

So where does the UK sit?

KPMG analysis of Pitchbook data found that venture capital backed startups and scale-ups in the UK to the tune of £19.4bn ($26.7bn) during the first three quarters of 2021. Each of these quarters was a record-breaker in terms of deal value – which hit £6.8bn in the third quarter.

This was more than double Germany’s or France’s totals. German startups raised a record €11.3bn (about $12.7bn) in venture capital funding in the first three quarters of 2021, up over 70% from last year’s overall total, according to PitchBook data, and similar to the amount France’s tech firms amassed. Cedric O, France’s minister for Digital, told Bloomberg: “London will have reasons to worry in the long run.”

The UK’s relative advantage compared with the rest of Europe is built on a strong research and innovation base and changes over the past decade by David Willetts when university minister to encourage student and faculty spinouts and startups as well as existing capital markets for investment from VCs and ties to international investors, particularly encouraged by the Department for International Trade (DIT’s) venture capital unit (VCU).

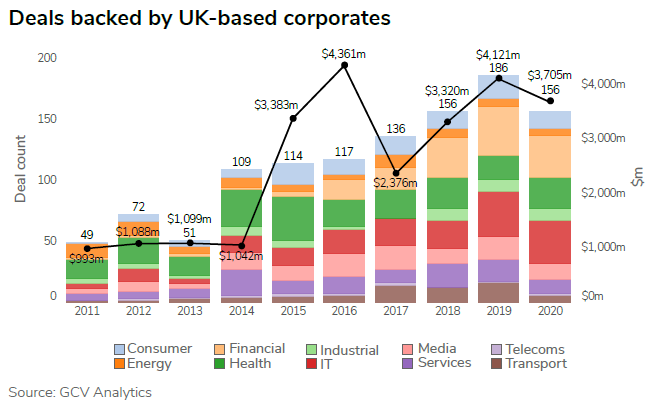

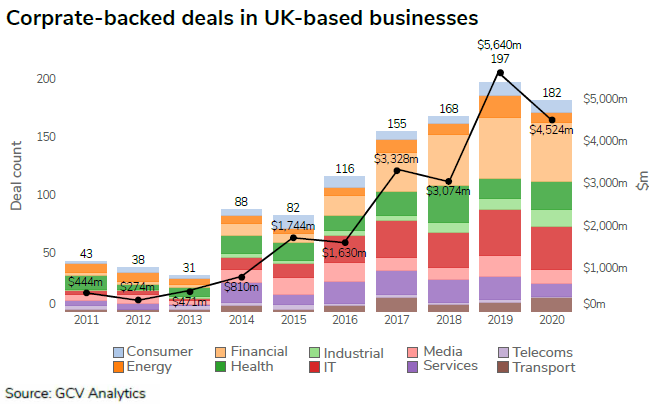

The missing link for continuous improvements has been relative paucity of UK domestic corporate venture capital (CVC) and a lack of training. There is a clear relationship between inward investors backing UK-based entrepreneurs and coinvesting with local CVCs.

So why are domestic UK corporations missing out?

As the Economist said: “The London Stock Exchange increasingly looks like a care home for old-economy companies, rather than a cradle for new-economy ones. Less than 2% of the FTSE 100’s value is accounted by tech firms, compared with 40% of the S&P 500’s.”

James Anderson, probably the UK’s only successful tech investor from public markets as manager of Scottish Mortgage investment trust managed by Baillie Gifford, was equally pithy when announcing his retirement in the summer.

A “deep sickness” in UK capital markets has stifled the growth of homegrown tech entrepreneurs and left London’s blue-chip FTSE 100 looking like an index from the 19th century. In a scathing critique, James Anderson, whose early bets on Facebook, Amazon and Tesla have made him one of the world’s most successful investors, said that too many UK asset managers are obsessed with short-term performance rankings and fearful of taking risks.

University of Sheffield-led research in July 2020 found 28% of FTSE 100 companies paid more in dividends and share buybacks than they generated in net income in their last available accounting year.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, many UK listed corporations have relatively underinvested in their innovation tools.

Research and development (R&D) refers to creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge. Total R&D In the UK in 2019, total expenditure on R&D was £38.5bn, £577 per head, or the equivalent of 1.74% of GDP, according to the UK parliament report this year. It was the equivalent of 1.84% of GDP in 1985.

The government has a target for total R&D investment to reach 2.4% of GDP by 2027, which would be still below the OECD average of 2.5% in 2019. R&D expenditure in Germany was the equivalent of 3.2% of GDP in 2019, in the US it was 3.1% and in France it was 2.2%.

Most funding for UK science and technology companies above £100m comes from international investors. US-based funds represent 40% of all investments between £100m and £250m in UK R&D intensive companies, compared with 27% from UK investors. For investments over £250m, 49% of investment comes from the US and 27% comes from Asia, compared with only 11% from UK investors. While this means that British companies are sought after by global investors, the lack of domestic growth capital holds back the ability of companies to scale up in the UK, often leading them to relocate to access global capital more easily, to sell early to foreign firms (and relocate their R&D activities), or to list on capital markets elsewhere. This comes at a cost to the UK economy as the financial returns, jobs and high impact R&D created by some of our most successful entrepreneurial teams goes to overseas capital owners.

Allied to internal R&D is open innovation tools, such as corporate venture capital (CVC), to improve links to external entrepreneurs and ideas.

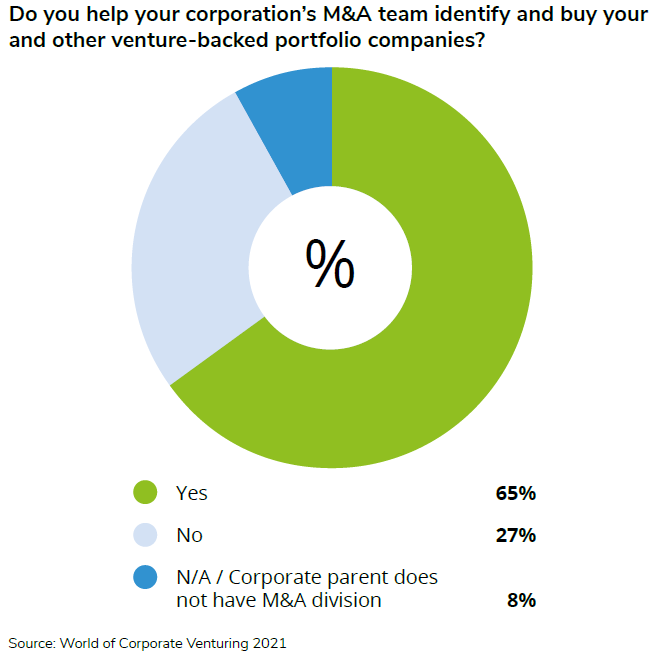

Lack of CVC, therefore, limits openness to new ideas and is also seen as a drag on R&D and M&A efficiency, according to management consultants BCG.

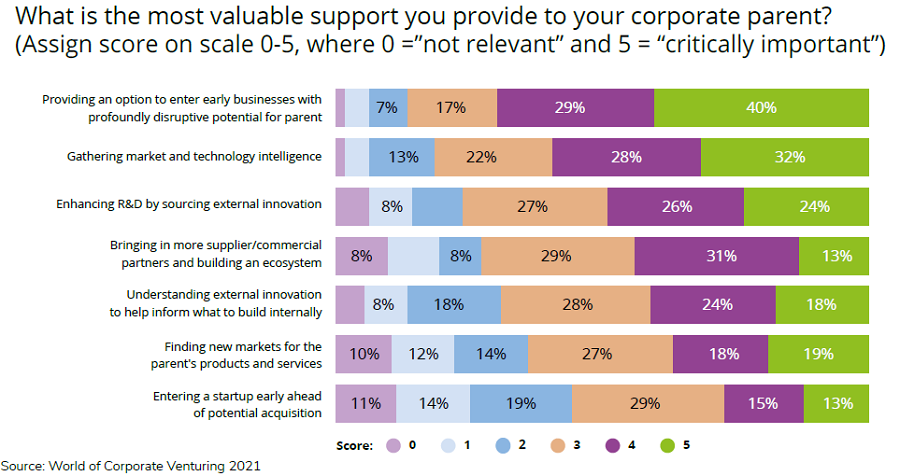

Nearly two-thirds (65%) of those 100-plus CVC managers surveyed by GCV in 2020 said their corporate venturing units collaborate closely with the corporate M&A division in identifying and buying companies, while almost a quarter (24%) said CVC was a “critically important” way to enhance R&D.

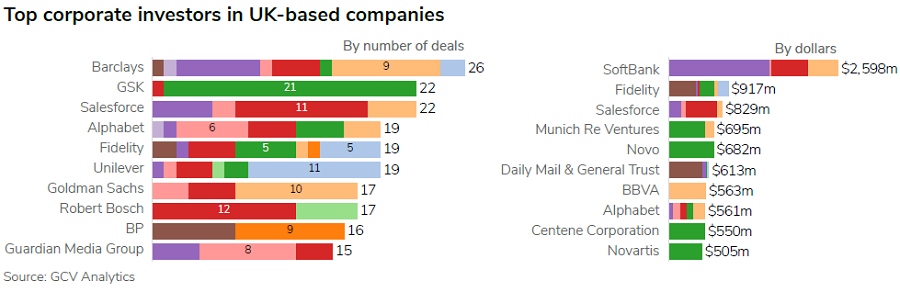

Less than half (49) of the current FTSE 100 constituents use CVC as a tool, according to GCV Analytics, with just 28 having a formal unit rather than making ad-hoc minority investments in private third-parties.

The impact can be seen more clearly when judged over time. The 283 prior constituents of the FTSE 100 had fallen out of the index through takeovers, mergers or lack of performance.

Only Sky had an active CVC unit before its takeover by Comcast, with another 20 having some limited CVC activity since being taken out of the index in an effort to improve performance.

But for those FTSE 100 companies, such as Unilever, RELX, BP and Shell, that grasp the importance of CVC it can help reposition the corporations and reenergise its stock. More should follow in their footsteps.

BP puts innovation at its core

A dozen years ago and UK-listed oil major had its corporate venture capital unit more at the margins of its operations, finding, investing in and working with entrepreneurial third-parties in and around its core business.

Now, the company says: “BP Ventures plays a key role in helping the company reinvent itself as an integrated energy company, in line with our new purpose: reimagining energy for people and planet. We will do this by investing in a portfolio of high growth technology businesses that will benefit and extend our core businesses, as well as open up opportunities in digital adjacencies. We will also invest in businesses that can help bp reduce carbon in its operations and production.”

The shake-up of the company’s entire staff under Bernard Looney has seen greater vigour injected into its open innovation toolset, which includes incubating ideas, taking minority stakes in startups (BP Ventures) around the world and building majority or control positions in scale-ups (Launchpad), such as Finite Carbon.

Having invested more than $500m and partnered more than 40 startups, the CVC unit has helped reimagine energy for the company.

References

https://medium.com/innovation-party/elon-musk-rate-of-innovation-vs-number-of-patents-590c0350e0d7

Economist https://lnkd.in/gTRvCMtz

James Anderson https://www.ft.com/content/81d47276-cf69-40ec-ad52-2f9e0df04ee3

And interviewed by James Mawson for GoFurther Forum November 9, 2021

https://mawsonia.app.box.com/s/fplmsj6r6nl5iv8o7y9mvrqekij6caqg

https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04223/SN04223.pdf

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn02791/

https://www.bcg.com/publications/2018/how-best-corporate-venturers-keep-getting-better

Data to be published this year in the book, Transformative Innovation, by James Mawson and Christine Gulbranson