Some say it is the job of the CVC investment professional, while others say business unit heads can be more effective on startup boards.

It is par for the course for corporate investors to sit on the boards of startups they invest in. But who is best place to take that board seat? Should it be a member of the CVC or someone from the relevant unit at the parent company?

Scé Pike, founder of AI startup Azurens, recently caused some controversy on the our webinar – Startups and Strategics – What works and what doesn’t – when she said that most startups prefer someone from the business unit to be on their board. All members of the webinar panel said they preferred to have someone in a platform or business development role on their boards. They see these professionals as the most useful in helping them gain commercial partnerships with the parent company.

But some CVCs balk at the idea of anyone but an investment professional sitting on boards. Members of the investment team are most able to meet their fiduciary responsibility to prioritise the interests of the startup rather than the corporate parent, they argue.

“Savvy startups expect that professional CVCs should understand what it means to be a good investor and board member or observer, and that their legal duty is to the startup first and the parent second,” says Liz Arrington, managing director of the GCV Institute.

“The potential for conflict of interest is a major reason that most CVCs have trained investment professionals as opposed to parent business executives holding board seats,” says Arrington.

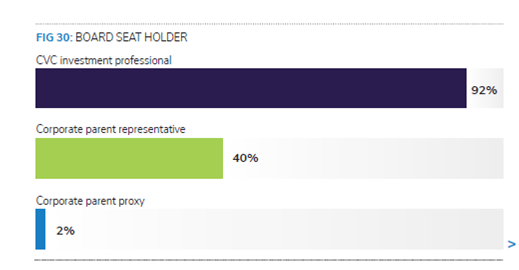

What happens in practice is a mixture, according to the results of nearly 400 CVCs who responded to Global Corporate Venturing’s most recent annual Keystone CVC benchmarking survey.

There are clearly strong arguments on both sides, so we asked three veterans of corporate venturing and investing to weigh in on who is best suited to serve on boards.

In camp CVC we have John Glushik, managing director of HG Ventures, the corporate VC unit of US industrial products manufacturer The Heritage Group, and Paul Asel, founding partner of NGP Capital, the CVC of Finnish multinational Nokia, who both believe that CVC investors are better suited to the duties and timescales of a startup board.

In camp business unit we have Terry Doyle, managing partner of Telus Ventures, the investment arm of Canadian telecommunications company Telus Communications, who says business unit members can be appropriate in some circumstances.

‘You’ve always got this spectre of conflict’ – John Glushik, HG Ventures

The demands of meeting fiduciary responsibilities as a board member means CVC investment professionals are best suited to that role, says Glushik.

Glushik has been going to board meetings as a venture investor in both financial and corporate VC for the past 25 years. On average he sits on six boards at any given time.

Being on the board of a private company means you are a fiduciary, which involves a number of different duties, says Glushik. “Many of those can often come into conflict with an executive or manager within a corporation, especially if you’re in a related industry or technology area, which almost by definition strategic investors are,” he says.

Company executives will often be put in a board seat role without properly understanding the fiduciary duty to the startup or have the time to dedicate to fulfilling board member duties, he says. “It is a dangerous position to be in if you’re an executive of a company and you have P&L responsibilities. If a conflict does come up, sometimes they won’t recognise it just from lack of experience.”

In cases when conflicts emerge, the company representative will often have to recuse themselves from their board role, which can lead to a board not being fully engaged and even deadlocked on making decisions.

Corporate investors, he argues, do not have the same accountability for managing financial performance of the business unit and are not involved in high-level strategic decision-making that can create conflicts of interest. “It is easier for the corporate venture member to say: I am a fiduciary to you, the portfolio company. I am going to keep all information separate from the company for which I work, and I am not going to be involved in the decision-making, for example, on how a commercial partnership might be structured.”

Startups should be wary about business unit representatives’ motivations for taking board seats. “You could have a business unit leader who has nothing to be gained from a portfolio company doing well.” In some cases, the business leader does not want the portfolio company to be successful because they are interested in buying the technology for as cheaply as possible. “But people don’t want to talk about that because it implies bad behaviour,” says Glushik.

‘The holder of the board seat should be there for the life of the business’ – Paul Asel, NGP Capital

Before taking a board seat of a portfolio company, corporates should consider the time commitment it requires. Ideally, the same person should sit on the board for the length of the investment, which could be a five-plus year commitment, says Asel.

This time commitment is not always conducive to corporate culture where turnover can be high at business units as well as at the CVC. “It’s very disruptive to the companies and reputationally to the corporate venture firm if they are plugging people in and out,” says Asel. “Whether it is a business unit person or a corporate venture person, it really has to be understood that they’re making that long-term commitment to the business.”

Startups crave the valuable help that a business development professionals can bring to their company, but this can be achieved by appointing them to an advisory board instead, says Asel. “One can tap talent and get help through an advisory role without having the fiduciary responsibility that is attached to the board role,” he says.

Unlike board seats, which have a long-term commitment, advisory board seats should change frequently – between one and two years – to suit the needs of the startup. “That way you are getting very situation-specific help on problems. Oftentimes the needs of the company will graduate beyond somebody. By having that short-term arrangement, it can actually work better for the corporate sponsor and the startup to have that advisory role,” he says.

Another option for corporate executives in business unit or platform roles is to take board observer positions. This does not require the same kind of fiduciary responsibility of a board seat and observers “can truly be there at the behest of the corporate sponsor,” says Asel. The GCV Institute plans to hold a webinar on observer roles later this year.

Ultimately, corporate investors can add strategic value to their portfolio companies without board involvement, says Asel. “I really believe strategic value happens through means outside of the board.”

‘The more you do this, the more you have a more nuanced view of how to do it’ – Terry Doyle, Telus Ventures

Terry Doyle describes Telus Ventures, the CVC he heads, as a very active investor that seeks to build out entire business lines for its parent through investments in startups. To achieve this, it aims to enter a commercial agreement within two years of investing in a company. “We feel that is one of our value-adds. Not only are we writing a cheque, which lots of people can do, but we can also become a customer,” says Doyle.

In cases when the CVC sees the opportunity to enter a commercial agreement with its investment, it will put a person from the business unit on to the startup’s board. “They’re usually bringing insight from our customer base or our problem-set to the startup,” says Doyle.

For investments where no commercial agreement is imminent, someone from the CVC team will sit on the board of the startup to monitor it from a financial perspective. About 50% of the CVC’s 85 investments have commercial agreements with the parent company.

What about the tricky issue of corporate employees having trouble carrying out their fiduciary duty to the startup? “I think there are absolutely instances where there can be a conflict, and this is why investing is a not a straightforward activity,” says Doyle. “But we all have an obligation at some point to do the right thing from a fiduciary perspective.”

The team is always upfront about its intentions before it makes an investment, says Doyle, whether this is its interest in acquiring the company or becoming a supplier. “The most important thing we have found to make us successful is to be very clear before we make an investment: here’s our strategy and here’s how we see the investment playing a part in that. That avoids a lot of the we’ll call difficult situations downstream.”

The CVC seeks both board and observer seats. It will ask for a board seat and sometimes also an observer role when leading an investment. Its typical cheque size is between C$10m and C$25m. “We have instances where a business unit person is sitting on the board and somebody from the CVC is an observer, and quite often it is the opposite.

“We aren’t pedantic in how we use the tools that are at our fingertips. We want to use them in a way which is appropriate for each particular investment.”