We look at some of the greatest corporate VC investments, from a $2.5m investment in a future $170bn company in the 80's to a deal in the wake of the dotcom boom that has produced $130bn.

A few months ago we looked at some of the least successful deals in the history of corporate venture capital – not a great list to be on. But it’s time to look at the flip side: the startup investments that have turned out to be immensely successful for companies.

Venture capital has been an important feature in new technology development for decades, going back to DuPont buying into General Motors during World War One, while companies such as Exxon began setting up their own strategic investment arms back in the 1970s. It is often hard to see whether a particular investment was astute or not until a good length of time has passed.

Daimler for instance paid $50m for nearly 10% of Tesla, now a $620bn business, in 2010 and sold those shares for $780m in 2014. Microsoft put $150m into Apple in 1997 and got for $550m that stake six years later, missing out on a potential $150bn bonanza.

But we’ve taken a deep dive into 10 deals that led to great outcomes: deals that led to outsized exits, huge corporate returns or a change to a company’s business or strategy. In this first part, we’ve looked at the best deals from the early and pre-internet era, at transactions that fuelled investors like Naspers and SoftBank long into their current run of activity. Tomorrow, in part two, we will cover a selection of deals that ended up taking its corporate VCs into new areas while opening new directions for their owners.

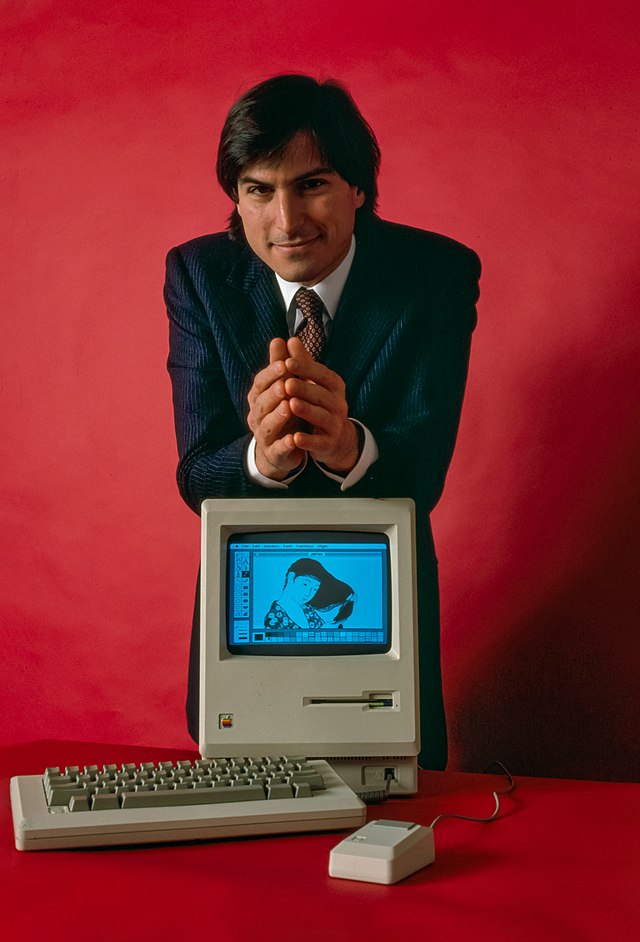

Apple into Adobe (November 1984)

Apple was only eight years old and just months past releasing the Macintosh, when it invested $2.5m in a fledgling software startup called Adobe in 1984, acquiring a 19% stake in the process.

Adobe itself had only been around since the end of 1982, and Apple had intially bid $5m to acquire the company. When that offer was turned down, it decided to buy a minority share instead.

What happened next?

Apple sold its stake in Adobe for $84m in 1989, when it was only mildly rather than obscenely profitable, but it had already generated some huge returns from its commitment.

Adobe’s inaugural product, PostScript, was the first international language standard for printers, and by 1985 it was being shipped with Apple’s LaserWriter printers, among the first to be tailored for the mass market.

The startup added graphics editing programme Illustrator later the same year and image-editing program Photoshop in 1989 and both were initially Apple Macintosh exclusives, as was video-editing tool Adobe Premiere in 1991. Those products helped establish an early image of Apple as a more creative and friendly alternative to PCs, and although Adobe may now be valued at a gargantuan $190bn, Apple continues to benefit from that association today.

Adobe into Netscape (April 1995)

Adobe was one of the computing businesses that joined telecom operators and chipmakers in setting up a wave of corporate venturing units in the mid-1990s, forming Adobe Ventures in 1994. The following year it joined media companies Hearst, Knight-Ridder and The Times Mirror in a series C round for a startup called Netscape, barely a year old, which had begun shipping its Netscape Navigator software just four months earlier.

What happened next?

Navigator was essentially the first internet browser and was initially the most widely used way to connect to what was then called the World Wide Web. It floated a few short months after its series C round, doubling its share price to $28 ahead of the IPO. Those shares closed at $74 on its first day and were trading as high as $174 before the end of 1995.

Adobe was not the only corporate VC in Netscape’s series C, but it invested in a strategic partnership that bundled its Acrobat software with Navigator, in effect making it the default printing software for online viewing and printing for at least two decades afterwards.

Adobe got out at the right time too, divesting its stake the following year. Netscape may have reportedly held an 80% share of the browser market at that point, but 1996 was the year Microsoft launched Internet Explorer as a free service, and it quickly began chewing up Navigator’s market share. Netscape would be acquired for $10bn by AOL in 1999 and its co-founder, Marc Andreessen, ended up having an okay career in VC himself. Maybe you’ve heard of his firm?

SoftBank into Yahoo (November 1995)

If Netscape’s IPO officially kicked off the dotcom boom, others weren’t far behind. Yahoo.com officially came online in January 1995 and three months later founders Jerry Yang and David Filo announced they were taking a leave of absence from their Stanford University PhD studies to run the startup full time, with a tiny bit of seed financing from VC firm Sequoia Capital.

Yahoo’s ‘online guide’ to the internet proved immediately popular and SoftBank, then a 14 year-old electronics media company, decided to make a bet with its newly launched corporate VC unit, SoftBank Capital. It reportedly paid $2m for a 5% stake in a subsequent round in November, three months after the startup began generating revenue. When Yahoo went public in 1996, SoftBank doubled down, paying $108m to boost that stake to 37%.

What happened next?

Yahoo’s shares skyrocketed once they hit the markets and peaked in early 2000, with a market cap of $125bn. Then came a long decline for the company, which spent big on platforms like Tumblr and Flickr without success, but it was slow enough for SoftBank’s shares to come in handy whenever it needed some quick cash for years afterwards, culminating in it selling its final 4% stake in 2011 to repay a $1bn loan.

Perhaps more importantly, the original investment led to SoftBank and Yahoo launching Yahoo Japan as a joint venture in 1996. In contrast with its US predecessor, Yahoo Japan is still huge, running the country’s most popular website and second most popular search engine, giving it a huge share of Japan’s online marketing revenue. The puncturing of the dotcom bubble may have reduced the monetary value of SoftBank’s shares (along with those in startups like E-Trade), but there was an even more lucrative investment around the corner.

SoftBank into Alibaba (January 2000)

If some of the biggest VC winners during the modern tech era have been the big US venture firms like Sequoia, KPCB and Benchmark, SoftBank’s advantage was that its proximity to Asia gave it an inside track. Sometimes that led to highly successful investments like a 1999 investment in two-year old search engine operator NetEase, now a $56bn company.

The most successful of those came in 2000 when SoftBank led a $20m round for Alibaba, which had been formed just months earlier as one of China’s earliest online marketplaces. The corporate boosted its stake in an $82m round four years later, at that time the biggest ever VC round for a Chinese company, by which time Alibaba was picking up serious steam.

What happened next?

Yahoo paid $1bn for a reported 40% stake in Alibaba in 2005, and in addition to getting nearly $100m a year in intellectual property fees through 2013, it sold $7bn of shares back to the Chinese company in 2013 and another $8.3bn in its 2014 IPO. But that was peanuts compared to what SoftBank got.

By the time Alibaba floated in 2014 it had grown into a monolith that included a suite of digital payment services, a thriving cloud services business and an entertainment offshoot. That record-breaking IPO raised $25bn and valued Alibaba at $230bn after the first day of trading, with SoftBank’s stake standing at over 32%.

SoftBank’s Alibaba shares have effectively acted as a piggy bank for the corporate since then, providing a buffer for the vast losses suffered by its Vision Fund. It sold $7.9bn of stock in 2016, $29bn in 2022 and over $7bn so far this year. Recent divestments have suffered from a hit to Alibaba’s share price after founder Jack Ma was made to step down amid Chinese government pressure in 2020, buy very few initial deals have produced as big a return.

Naspers into Tencent (May 2001)

Alibaba was not the only early internet startup in China to get corporate investment up front. Dell led search engine operator Sina’s 1999 series C round, while Google invested in Baidu and Dianping in the mid-2000s when each was valued below $200m.

But the most lucrative of all came from South African newspaper publisher Naspers. The company had diversified into pay TV and web portals before it paid $32m for a 46.5% stake in Tencent, the creator of instant online messaging service QQ, in 2001.

What happened next?

QQ grew to nearly 650 million users by 2010, the year before Tencent launched the even more successful WeChat, currently at around 1.3 billion monthly users who message, call, shop and pay for goods through the app. If anything, its gaming business has been even more successful.

As for Naspers, that 46.5% stake would be worth about $187bn today had the corporate held on to it fully. Instead, it sold off an initial $10bn of shares in 2018 and a another $14.7bn three years later, the returns supporting an ongoing international expansion driven by corporate venture investments, with India, Brazil and the Netherlands particular points of interest.

Naspers’ parent company, Prosus, continues to divest shares, most recently last month, to finance a share buyback, and although the percentage of Tencent it holds has fallen below 26%, that still represents about $105bn of value. Not bad for a $32m outlay.

Part two: The birth of a new model of CVC and an early look at what would be the world’s most popular website.