Editor-in-chief James Mawson ponders what lies ahead for corporate venture capital.

Five years ago, the GCV editorial argued that “with US President-elect Donald Trump selecting fellow billionaires and investment bank Goldman Sachs alumni to his team, Europe fracturing under divergent member state aims and Russian pressure, and Asia grappling with China’s crackdown under President Xi, a Panglossian degree of optimism is unwarranted about the economy or much else”.

Half a decade on and the same geopolitical concerns seem to remain (though Trump’s first term has finished he remains influential among his supporters). Judging, however, by the markets and it seems like there are few, if any, cares even with the populist swing to a new “Buenos Aires Consensus” of fiscal spending and higher inflation and hence interest rates.

The yield on two-year Treasury bonds (0.6%) or 10-year bonds (1.44%) are very low by historical standards and much lower than the current rate of inflation (6.8% in the US).

In the US, equity valuations are very high, as measured by the cyclically adjusted price-earnings (Cape) ratio developed by Robert Shiller of Yale University, which compares share prices with the average corporate earnings of the past 10 years. The current Cape ratio is 38, a level that was only higher during the peak of the dotcom bubble of 2000, according to the Financial Times in Philip Coggan’s excellent analysis – check out his keynote speech from his latest book, More: The 10,000-Year Rise of the World Economy, at the GCV Digital Forum.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, a wall of money has entered the innovation capital economy in the search for returns. Last year saw records broken in all areas – from investments to exits and fundraising and ever-increasing numbers of corporations start their venturing programmes.

Consultants McKinsey’s survey of executives, The State of New-Business Building, found that by 2026 they expected 50% of global revenues would come from products, services, and businesses that do not exist today. A lot of the money will be soaked up by the duplication of assets required by geopolitical and supply chain tensions. But at least some will flow to the infrastructure transition to tackle climate change through electrification, hydrogen, storage and distribution and opportunities in healthcare through personalised medicine and new information and communication tech, such as compound chips, quantum and photonics.

This macro picture and strategic driver pushing innovation and hence growth is helpful to the corporate venture capital (CVC) industry.

The requirement identified five years ago by GCV that venture investing was moving “from a cottage industry of VCs following ‘pattern recognition’ to select former colleagues, fellow university alumni and sons of friends” to one where “the newer breed of venture investor has emerged with the brand, marketing and support-beyond-money that entrepreneurs want”.

This new breed has blossomed, but two issues remain when looking at GCV’s annual survey of 200-plus investors around the world.

First, the record number of new CVCs if they are perceived as dumb money brings a risk of tarnishing even the good investors. The top 20% of investors – as benchmarked by GCV Analytics’ rigorous qualitative and quantitative analysis – have, through the GCV Leadership Society, stepped up to this challenge and given back to the community through their mentorship and insights within the GCV Institute.

The Institute has trained hundreds of professionals over the past year both at new and existing CVC units and, crucially, at the parent companies so they can better land the value of working with entrepreneurs and portfolio companies. Having a professional investor base also attracts and retains the right sort of talent to the industry, as witnessed through the GCV Rising Stars and Emerging Leaders awards.

This delivery of the promise of professional corporate venturing to add value to both startups and corporations requires support as customers and suppliers as well as product and service development.

The second challenge is, despite these efforts, the wall of cash and competition from investors to work with the best entrepreneurs remains intense. To win deals, CVCs are tending to go both earlier-stage as well as provide bigger cheques to later-stage rounds with clear strategic alignment. The latter is easier if they have a track record, such as Boeing, Telstra, Swisscom or SAP’s Sapphire, that enables them to raise third-party capital.

The good corporate venturers are also making more of their internal talent to incubate or build ventures, potentially with external funding to support the portfolio companies and validate the opportunities they see.

Effectively this starts to reverse the outside-in innovation toolset. Once the culture and innovation capacity through use of corporate venturing professionals is utilised to aid more efficient mergers and acquisitions and research and development departments then the overall corporation has reached its transformative innovation stage and can offer the inside-out opportunities.

The past decade has seen the golden age – when just about any deal would do well because the competition from most VCs was amateurish and venture capital was still a cottage industry – pass into the professional era of blurred private and public capital markets bringing more efficient allocation of capital to those who can use it best.

The next year and decade will see the entire entrepreneurial ecosystem start to scale-up to reach its potential as ideas and technologies build on themselves – ideas discussed in GCV’s next book, Transformative Innovation, to be published next month.

There is much potential outside of the US, which still accounts for nearly half of the record-breaking $600bn-plus venture dollars invested last year.

Even though venture funding to Latin American or European startups grew the most, by more than 300% and 150%, respectively, year-over-year, according to Crunchbase, their totals were still relatively small compared with gross domestic product or population and the financing needs of their economies. With close to $20bn invested in LatAm in 2021 and $110bn invested in Europe the sums seem impressive only compared to with the paucity of capital available before.

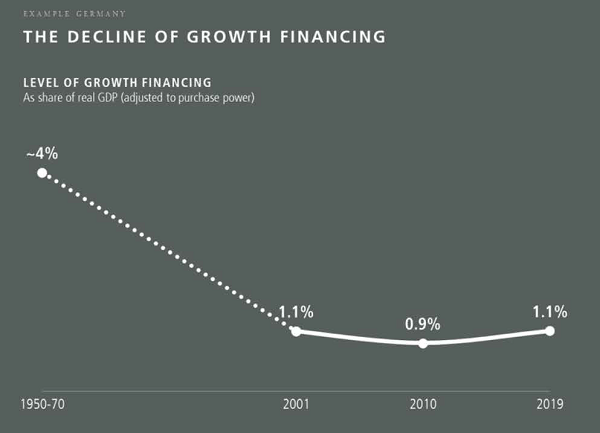

VC firm Lakestar’s analysis of the financing gap takes Germany as an example (see graph above) and shows how it has declined relative to its recent past but also how little innovation value it delivers compared to the US (less than a tenth).

In this era, the winners will be those that, like SoftBank’s founder, Masayoshi Son, have kept their eyes fixed on the future, looking 100, 200 or 300 years ahead rather than paying too much attention to the passing obsessions.

“Are all of these decisions taken to protect minuscule interests bound by geography with a small-scale sense of justice and a short-term mindset really for the greater good of humanity?” he asks in his biography, Aiming High: Masayoshi Son, SoftBank Group and Disrupting Silicon Valley, by Atsuo Inoue.

Looking back 250 years to the crucible of the first industrial revolution shows the financial, cultural, ethical and political ambitions required to win. As Scottish philosopher and political economist Adam Smith said then: “Wealth is power.”