From hiring foreign attaches to developing technologies for the commercial market, here are tips that defence tech companies should keep in mind when selling to the government.

The recent rise of large geopolitical conflicts such as the wars in Ukraine and in Gaza, Israel, has led to a resurgence in defence tech investment.

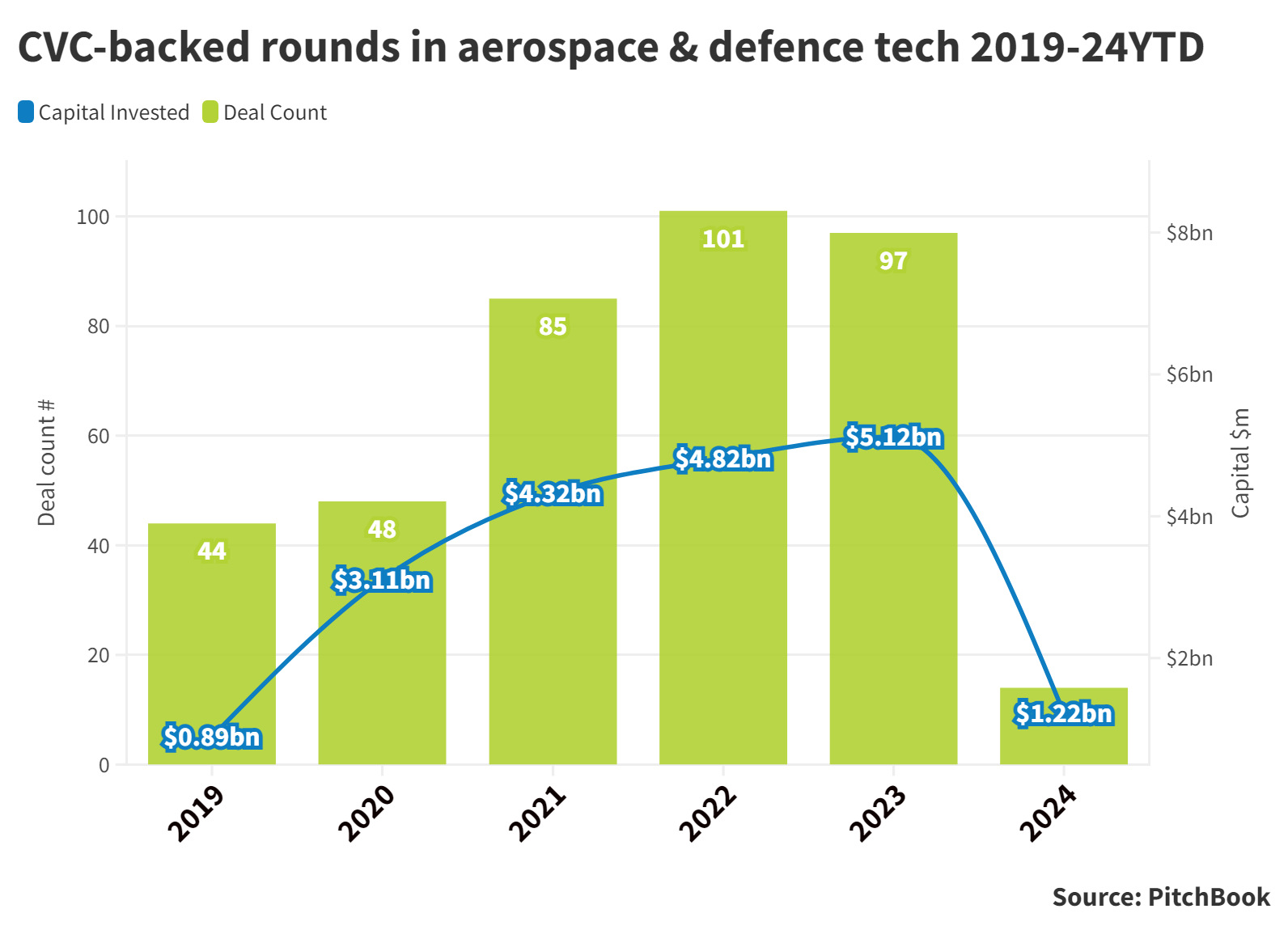

The dollar value of corporate venture capital-backed financing of defence startups increased by nearly fivefold between 2019 and 2023 to $5.12bn, according to Pitchbook data.

The increased demand for defence technology has coincided with a decline in government budgets for spending on national security. Governments have increasingly sought more external sources of defence tech as their own research and development budgets have declined.

“Many of the leading technologies such as AI are being developed outside of the government market and brought into the sector by large technology companies or VC-backed startups,” says Ryan Lewis, partner at SRI Ventures, the investment arm of research organisation SRI International. “As a result, the US government has become increasingly open to nontraditional suppliers to service those types of emerging technology needs.”

But procuring government contracts is not an easy feat for startups. There are many hoops to jump through and it can take a long time to enter agreements to supply branches of the military with a new technology.

Interested in more on defence investing?

Global Corporate Venturing runs a Global Defence Council to provide a platform for CVCs in the defense sector to connect and explore innovation and investment opportunities. Find out more about the Global Defence Council here.

Here is a list of pitfalls that startups should avoid when trying to gain government contracts.

1. Don’t develop technology that only has a military use

Many investors will only commit capital to startups that have defence technologies that are also developed for the commercial market. Defence tech CVCs such as Booz Allen Ventures, the CVC of the US military contractor, primarily invest in these so-called dual-use technologies because the long time it can take to sell to the government does not chime well with the commercial milestones set by investors.

It can take government departments between 24 and 36 months to enter commercial agreements. Startups often don’t have the capital to last through the entirety of that sales cycle.

But once startups land a government contract, it can be a big market opportunity. The contracts tend to last a long time and can be a consistent source of revenue while startups build their commercial businesses.

The government also benefits from having dual use technology because it means it will be updated. This is the less the case when a technology is developed specially for the government. “It becomes a piece of shelfware – it may initially be useful for the specific mission that it was envisioned for, but it doesn’t get better over time,” says A.J. Bertone, managing partner at IQT, the not-for-profit strategic investor for US national security. “With commercial-first technology, the government is able to benefit from all the innovation that continues to flow into the commercial product.”

2. Don’t expect your regular sales team to also sell to the government

Selling to the government requires different skills compared to selling in the commercial market. Teams trying to procure government contracts may need to become adept at specific skills such as lobbying. “It is fairly tricky for a company to be able to play both sides effectively. You need different teams or different skills sets,” says Kiichiro DeLuca, partner at Weru Investment, a Japanese asset management company with a VC arm.

Procuring government contracts can also require dual-use startups to set up firewalls between their commercial corporate entity so that they can do more sensitive work with government. US listed company Planet, formerly Planet Labs, for example, set up a subsidiary called Planet Federal to create a firewall with its commercial side of the business, which provides satellite imagery and geospatial technology. This is to maintain confidentiality required for government projects and customers.

3. Don’t ignore small business loans as a way to get to a foot in the door with a government department

Applying for government funding programmes is a good way to get to know a department or agency and to find out if they could be a potential customer. The US’s Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) programme, for example, allows small businesses in the US to collaborate with a government research body with the potential to commercialise their product.

“SBIR or other non-dilutive financing can be a good way to get your beta product or service to market initially,” says Lewis. “The award can also serve as a way for startups to learn more about potential customer needs, emerging contracts and programmes.”

4. Don’t be afraid to get help figuring your way around government agencies

The plethora of government agencies and military services that offer contracts to startups can be confusing to new companies that have not worked with government before. That is the reason that it is a good idea to get an adviser or investment firm specialising in helping startups access government. “You need somebody to shepherd you through this,” says Bertone. “This is a market that is extremely unforgiving. To first timers it is full of landmines. It’s labyrinthian. It’s extremely opaque and very hard to navigate.”

Companies such as IQT and SRI Ventures are examples of investors that have close ties to government and specialise in helping startups gain government contracts.

5. Don’t forget to hire a local advisor when you are selling to a new country

An increasing number of dual-use startups choose to do business internationally with allied nations. This brings up its own challenges of needing to navigate different government approaches to contracting with startups. “The defence world is very different in every geography. It’s a very localised challenge,” says DeLuca, of Weru Investment.

He advises startups to work with local advisers that have contacts in government and that can speak the local language. “It’s almost like staffing an embassy of sorts. You have an attache specifically for that purpose.”

RELATED STORY

Investors set sights on defence tech

Defence is turning into an alternative revenue stream for software technology, following the cooling of recent bull markets for tech.