UK corporates invest in the domestic innovation ecosystem less than US, French and German peers. The government is trying to change that.

Photo by sagesolar on PxHere

The UK’s much-publicised plan to become a science and tech superpower has one big weak spot — UK corporations are failing to invest in the country’s startup ecosystem.

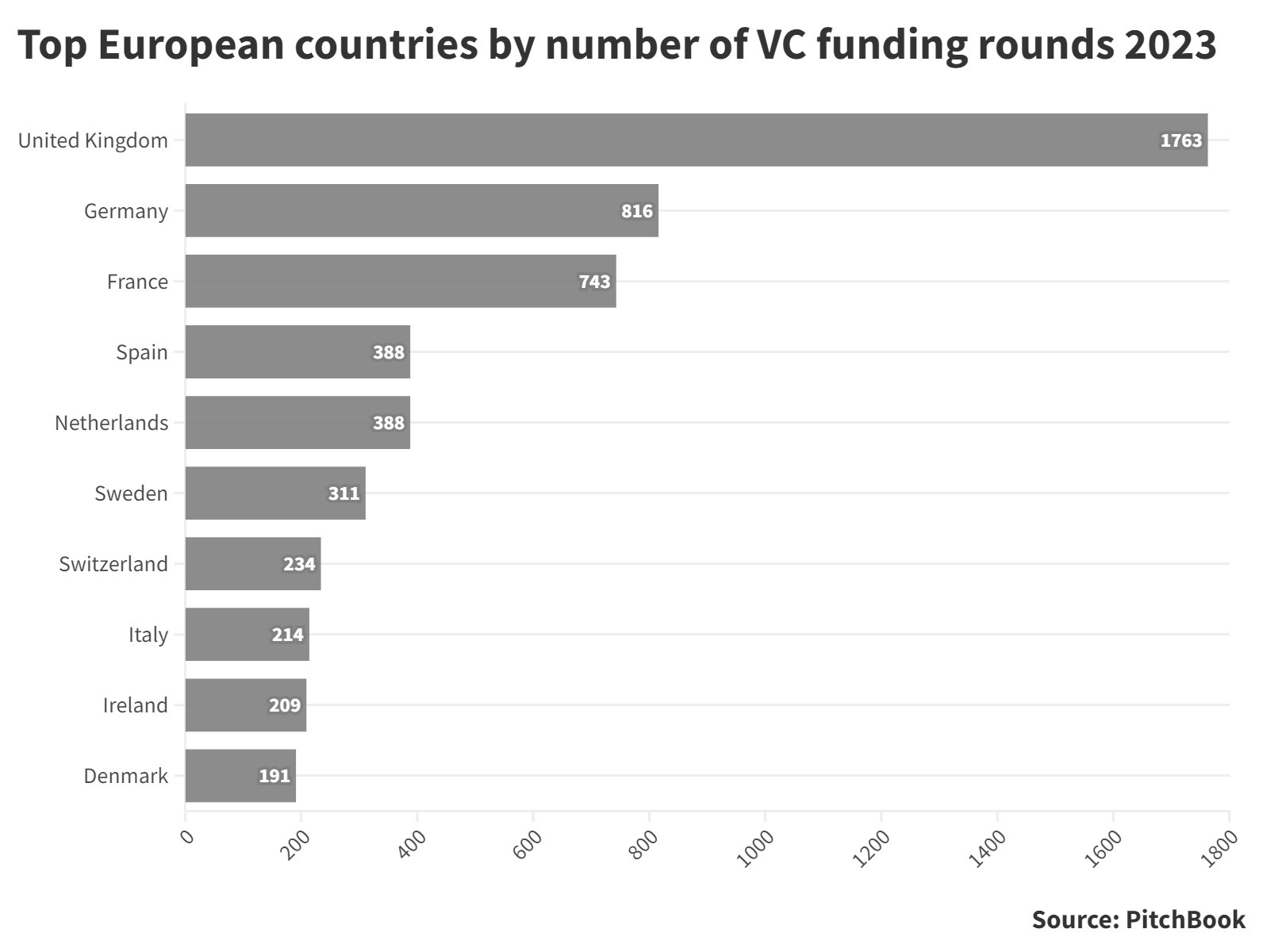

The UK has Europe’s most active venture capital market, with 1,763 startup funding rounds totalling $18.7bn according to PitchBook, more than France and Germany put together. But the country lags behind other western economies in the amount of capital that its corporates invest in startups in their own country.

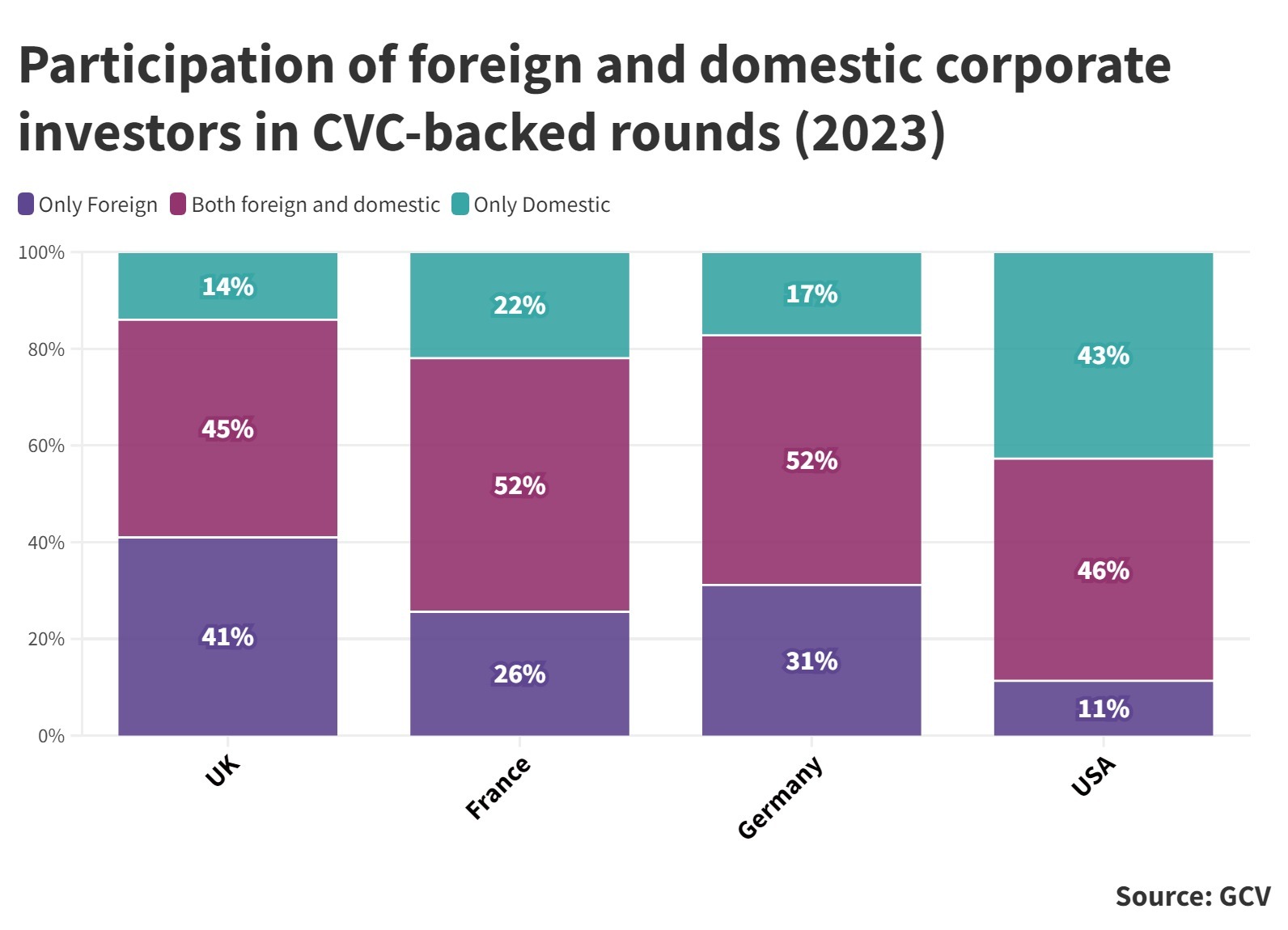

Forty-one percent of corporate-backed funding rounds in the UK have no UK corporates in them at all, a much higher percentage than in France and Germany. Only 14% of corporate-backed rounds in the UK come from only domestic corporates. This is a far cry from the US where 43% of corporate-backed rounds are US companies investing in US startups.

The government is now trying to change this, starting with a series of roundtables with members of the corporate venture capital community and UK companies that are open to venture investing.

George Freeman, who was until recently the UK’s minister of state for science, technology and innovation, told an audience attending GCV’s Summit in London in June last year that he wanted to draw corporate venturers into the UK’s startup tech sector. “I am trying to create some really tangible opportunities for deep, long corporate venture investing in our ecosystem,” he told delegates.

Paul Morris, lead on corporate venturing activities for the UK government’s Department for Business and Trade, is part of the efforts to encourage UK corporates to set up CVC units.

“The UK has a lot going for it, so it seems strange that the UK doesn’t have more homegrown corporate VCs,” says Morris. “The government has a strong desire to increase and support investment in science and technology. UK corporates having VC units is seen as one element that helps drive that openness to innovation.”

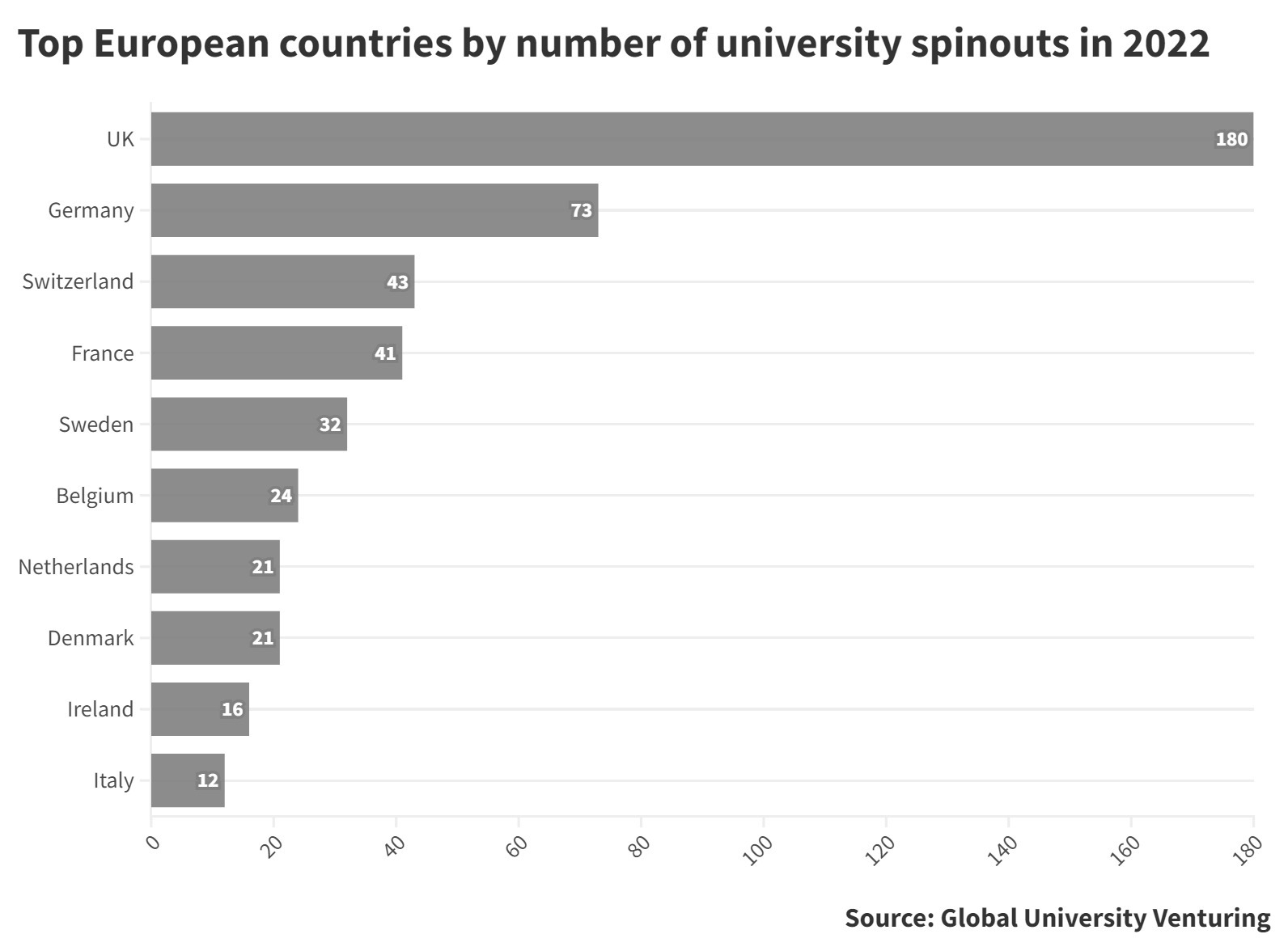

In two aspects of innovation the UK performs well: university spinouts, and research and development. The UK produces the most university spinouts of any European country, with 180 businesses formed out of university research in 2022, compared with 73 in Germany, the country with the second largest number of spinouts.

The UK ranks fourth of the G7 countries in 2022 in total spending on R&D as a percentage of GDP, according to OECD data.

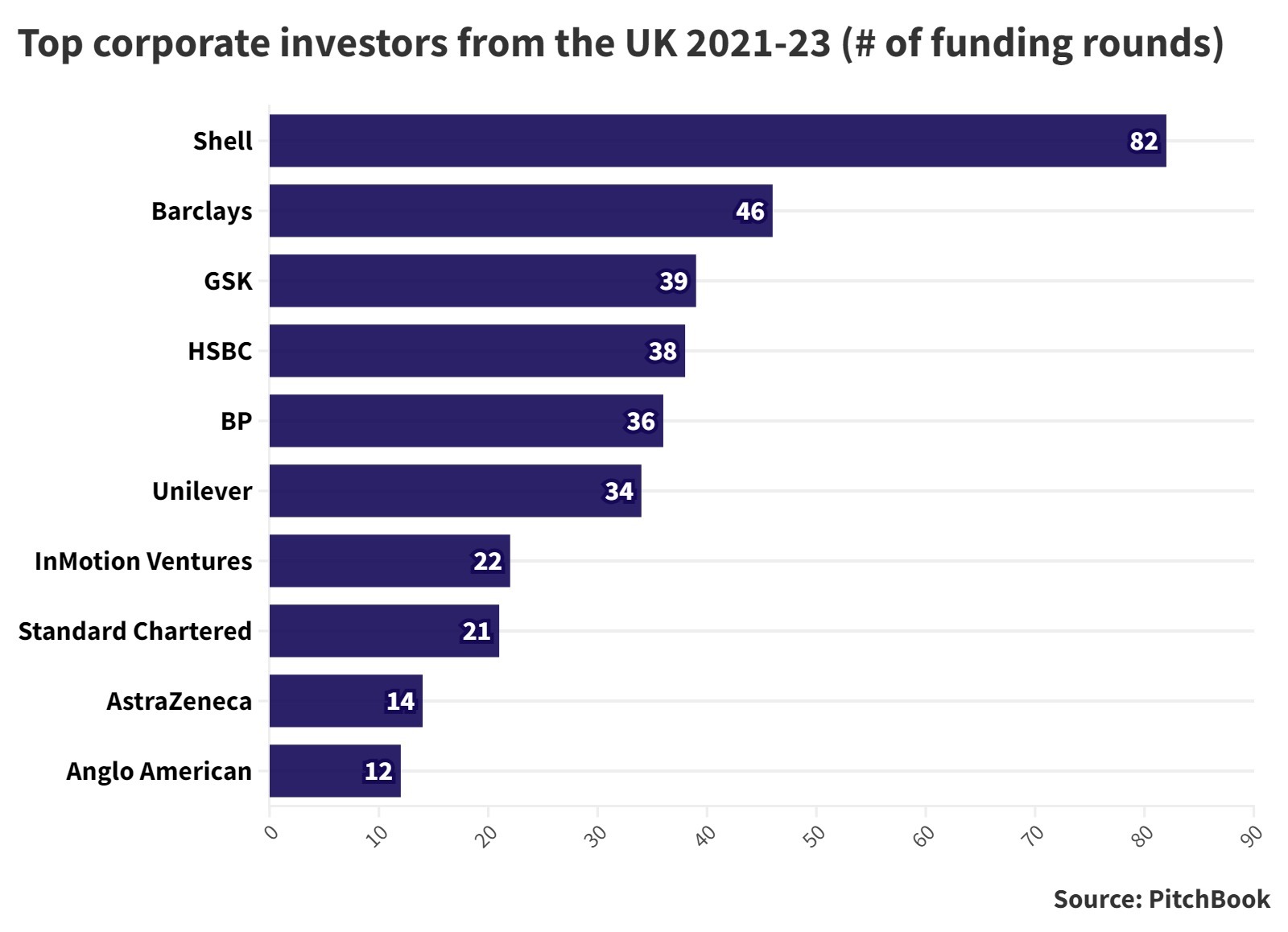

Some UK corporates are active investors in startups. Oil and gas majors Shell and BP are in the top five UK corporations for the number of funding rounds they participated in between 2021 and 2023. Banking groups Barclays and HSBC are also active. But, overall, GCV data show a lacklustre picture of venture investing in domestic startups among UK corporates when compared with other countries investing in their own tech ecosystems.

“There is a lot of international capital in the UK because we’re so strong at R&D, because we have a talented workforce. We’ve got great startups because we have got great universities. And we’ve got great scale-ups. The question is around domestic corporates investing in UK innovation,” says Saul Klein, partner at Phoenix Court and member of the Council for Science and Technology, which advises the UK prime minister on science and technology policy issues across government.

Klein, an investor and founder of several startups, draws a parallel between the lack of share price growth of the FTSE 100, the index of the 100 largest companies listed on the London Stock Exchange, and the UK’s lack of investment in innovation.

The stock value performance of the FTSE 100 has lagged behind that of the S&P 500, an index tracking the performance of 500 of the largest companies listed on stock exchanges in the US.

“The adoption of technology and innovation within the US economy would suggest that there is a correlation between the increase in share price value growth in companies and their adoption of technology and innovation,” says Klein.

The UK needs to find a way to create some momentum for CVC unit formation. One way to do this is to create public-private partnerships that encourage corporates to invest alongside government. In Germany, High-Tech Gründerfonds, a public-private venture capital investment firm, has encouraged German corporates to invest in seed-stage companies. Investors in its fourth fund include 45 companies from a range of industries, including medium-sized businesses and family offices.

In the UK, the government has encouraged institutional investors to invest in technology startups through the formation last year of its Long-term Investment For Technology and Science initiative. But this does not include corporates.

“The adoption of technology and innovation within the US economy would suggest that there is a correlation between the increase in share price value growth in companies and their adoption of technology and innovation,”

Saul Klein

Peer group pressure to invest in technologies could be what is lacking among the UK companies, says Morris. “There is sometimes a herd mentality to CVC formation. If you see other corporations in your sector or geography setting up CVCs, you follow as well. If your major competitors have set up corporate VC units and you are the only one that hasn’t, you may think you are missing a trick.”

There are a few signs that more UK companies could step corporate venture investments. The UK government-owned high speed rail company, HS2, for example, plans to launch a public-private investment fund with companies from HS2’s supply chain.

BAE Systems, a UK defence contractor, too is open to the idea, although Michelle Le Merre, finance director in corporate development and strategy at BAE Systems, stresses that the company has no immediate plans to launch a separate CVC arm. BAE invests in companies by taking minority stakes, acquiring them outright or entering commercial supplier agreements through its corporate development function.

“We’re happy with the current strategy of investing in venture as part of a broader strategy offering and doing it on an individual basis rather than having a separate fund that’s dedicated to it with a separate team,” says Le Merre. She adds that in the defence sector there have been “mixed experiences on the success of CVCs.”

“I feel we currently address the innovation and VC investment need without having to have a separate structure,” says Le Merre.

The UK’s Department of Business and Trade plans to run more roundtables to spread the word about CVC in an effort to create more momentum towards CVC creation.

But, in the end, it is up to corporates — and the pressure of their board members and shareholders — to take the leap into venturing. “One has to go back to educating boards and large shareholders that if you still want a company to be valuable 10 years from now, you should challenge leadership teams to have these capabilities and plans in place,” says Klein.