There will not be enough rare earth metals to make the magnets industry needs in the next decade so the race is on to find alternatives.

Consumer electronics company Samsung and car parts manufacturers Allison Transmission and Magna have become the latest corporate investors to back Niron Magnetics, a US startup that has developed a new magnet technology that avoids the use of rare earth metals.

Industrial companies are under pressure to find new magnet technologies as supplies of the rare earth metals needed to make strong permanent magnets are in limited supply — and what little there is is mostly controlled by China.

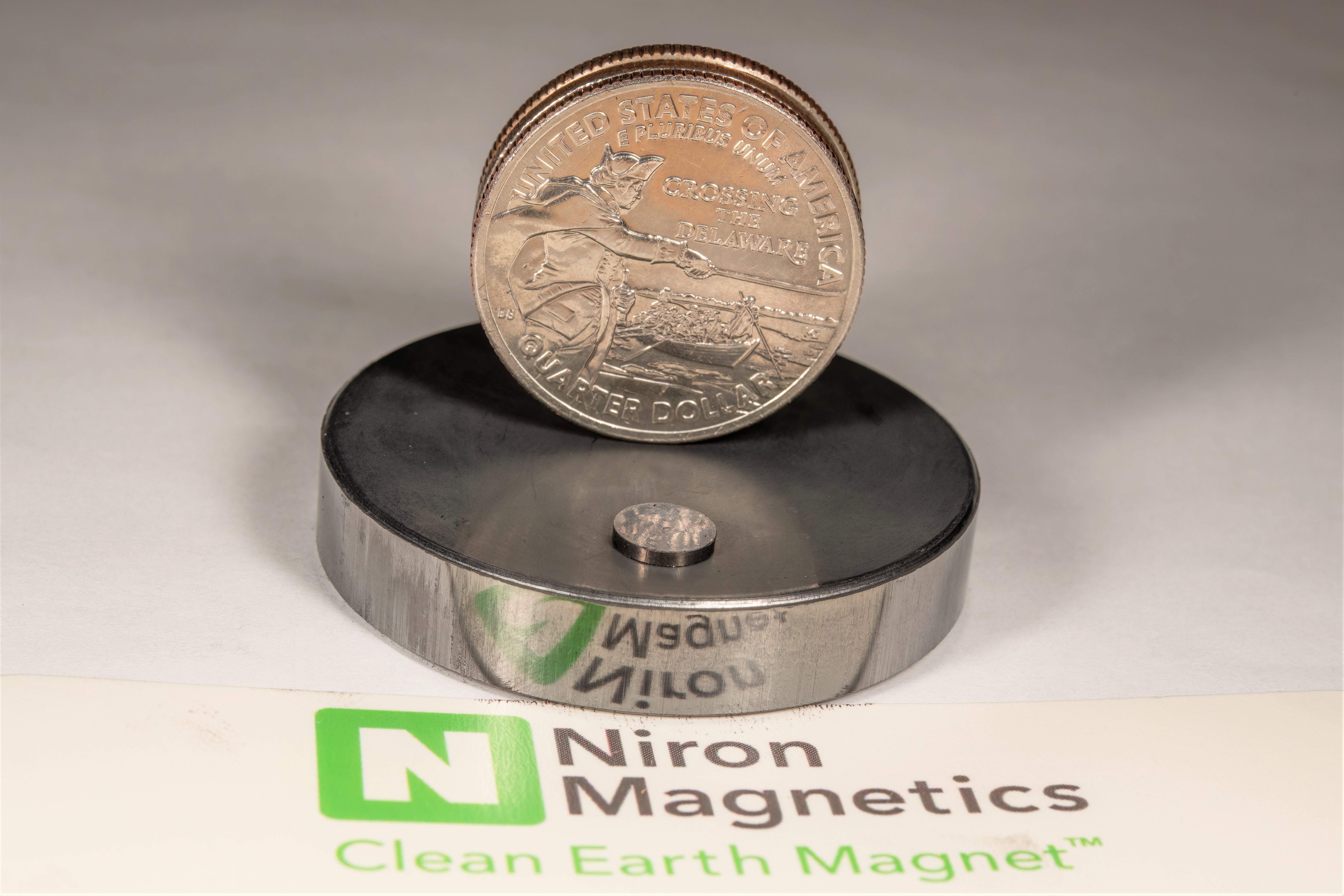

It is no wonder, then, that corporate investors, including General Motors, Stellantis and Volvo Cars, have been racing to back Minnesota-based Niron, which has developed a way of making magnets using iron nitride, a chemical compound made from iron and nitrogen, rather than rare earth metals like neodymium and cobalt.

“It’s the first new magnetic material in 40 years, and we’ve perfected how to make that material at scale,” Niron CEO Jonathan Rowntree tells Global Corporate Venturing. “We’re currently scaling the technology and what’s great is that it really solves major three problems with rare earth permanent magnets today.”

Permanent magnet demand is predicted to triple over the next decade but there is only enough rare earth metals to cover double.

Not only does the mining and processing rare earth metals have a big environmental impact — Rowntree claims 2,000 tons of hazardous and even radioactive waste can be produced for every ton of magnets — but magnets have become a geopolitical flash point, with China controlling some 90% of rare earth ore processing.

“They really control the pricing and supply of that, and they’ve started to use that as a way to combat some of the tariffs and trade restrictions the US has placed on exports of semiconductor technology equipment,” he explains, adding that this factor is currently the biggest concern for corporates, which need a steady supply of magnet materials for their products.

The third issue is that there is set to be a huge shortfall between supply and demand in the coming years as the world looks to move from fossil fuels to electrification. Permanent magnet demand is predicted to triple over the next decade but there is only enough rare earth metals to cover double. In fact, Rowntree says, by 2035 the shortage of rare earth metals will actually be bigger than the market is today.

“That’s where our iron nitride technology comes in,” he adds. “It’s an 80% to 90% cleaner process than with rare earths. We’re using readily available raw materials, iron and nitrogen, so we can manufacture them anywhere in the world. And we intend to build significant plants in the next several years, to provide a significant portion of the demand required to fill that gap.”

Niron Magnetics, a spinout from the University of Minnesota, has raised over $160m since it was launched in 2014. This $25m round was led by Samsung through its Samsung Ventures unit, investing together with automotive part manufacturers Allison Transmission (through its Allison Ventures subsidiary) and Magna in addition to Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community and University of Minnesota itself.

Why Niron’s corporate backers are set to be its first customers

Niron now has a wide range of corporate backers covering a lot of technological ground, Rowntree says.

“GM and Stellantis invested in November, and they’re top-five global automotive OEMs (original equipment manufacturers),” he says. “What’s great is that in this round, we have some of the largest tier-one suppliers to carmakers, Magna and Allison, investing. Again, that completely validates the potential for EVs.

“About 25% of the magnet market is in audio”

“With Samsung Electronics, there’s a lot of potential in the shorter term for us in consumer electronics, mainly around audio applications. About 25% of the magnet market is in audio. They go into speakers, and the material we’re launching later this year is very well suited to audio applications. So, we’re excited about the collaboration and partnership with Samsung to bring those products to market.”

The corporates are investing in Niron as strategic customers and working with it to test and develop its technology for a variety of uses. You could end up seeing the magnets in both the tiny accessory motors that make a car’s power windows go up and in its electric motor. Other potential areas include heating, ventilation and air conditioning units, industrial motors and brick-sized magnets for use in wind turbines – an area it is looking to enter in late 2024 or early 2025.

Expanding to larger magnets will however involve scaling up Niron’s manufacturing capabilities, and the company has ambitious plans on that front. It is set to complete its pilot plant this year, allowing it to conduct performance and reliability testing with its partners. Then, it intends to build out a low-volume production facility in 2025, most likely in Minnesota.

The next step will be to move to high-volume production, and Niron has already begun a nationwide search for a site. The company aims to expand the initial commercial plant in 2026 while it builds a high-volume plant it can bring online the following year. But it is targeting a more gradual approach than the gigafactories constructed by battery startups like Northvolt and Verkor.

READ MORE:

Allison seeks commercial and military vehicle innovations through CVC

The transition to electric mobility means fewer vehicles need transmissions, so Allison is looking for new business ideas from startups.

“We will probably do another round late this year or early next year that will really be targeted around funding the expansion to high-volume manufacturing scale,” Rowntree says. “We will be investing not just tens of millions but hundreds of millions of dollars to build that high-volume facility, but the plan is that we wouldn’t build that all in one go.

“We would build the infrastructure for that and put the first few manufacturing lines in place. Then, as we match demand and sign offtake agreements with customers, we can then raise the investment to build out that factory.

“I think a lot of these battery companies have gone for the big-bang approach and that’s not the one we’re taking. It will be a phased investment matched with our qualifications and offtake agreements with customers. The same strategic customers we’ve got investment from recently will most likely be the first customers.”