Andrew Chang, MD of United Airlines' venture unit, tells us sustainable jet fuels like that of portfolio company Viridos are a strategic priority, but how viable will they be long term?

Airline carrier United’s sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) fund provided $5m in a $25m round for algae-based jet fuel developer Viridos this week in the wake of the latter’s largest corporate partner stepping back.

The series A round also featured oil and gas provider Chevron and the cash will fund further research and development for the startup’s technology, which Andrew Chang, managing director of corporate venture unit United Airlines Ventures, says is a big part of the airline’s decarbonisation strategy.

“As with all aviation, 98% of our emissions are derived from the consumption of jet fuel, so the single most impactful way we can decarbonise is to look for alternative sourcing non-fossil-based liquid hydrocarbonates for jet fuel,” he tells Global Venturing.

Air travel is responsible for around 2.5% of global carbon emissions and by late 2022 the number of travellers was nearing the levels it was prior to the coronavirus pandemic. United is also looking at hydrogen fuels and electric batteries but Chang says neither has the levels of density required for jet fuel and so most of its work in the area involves seeking out more sustainable fuel sources.

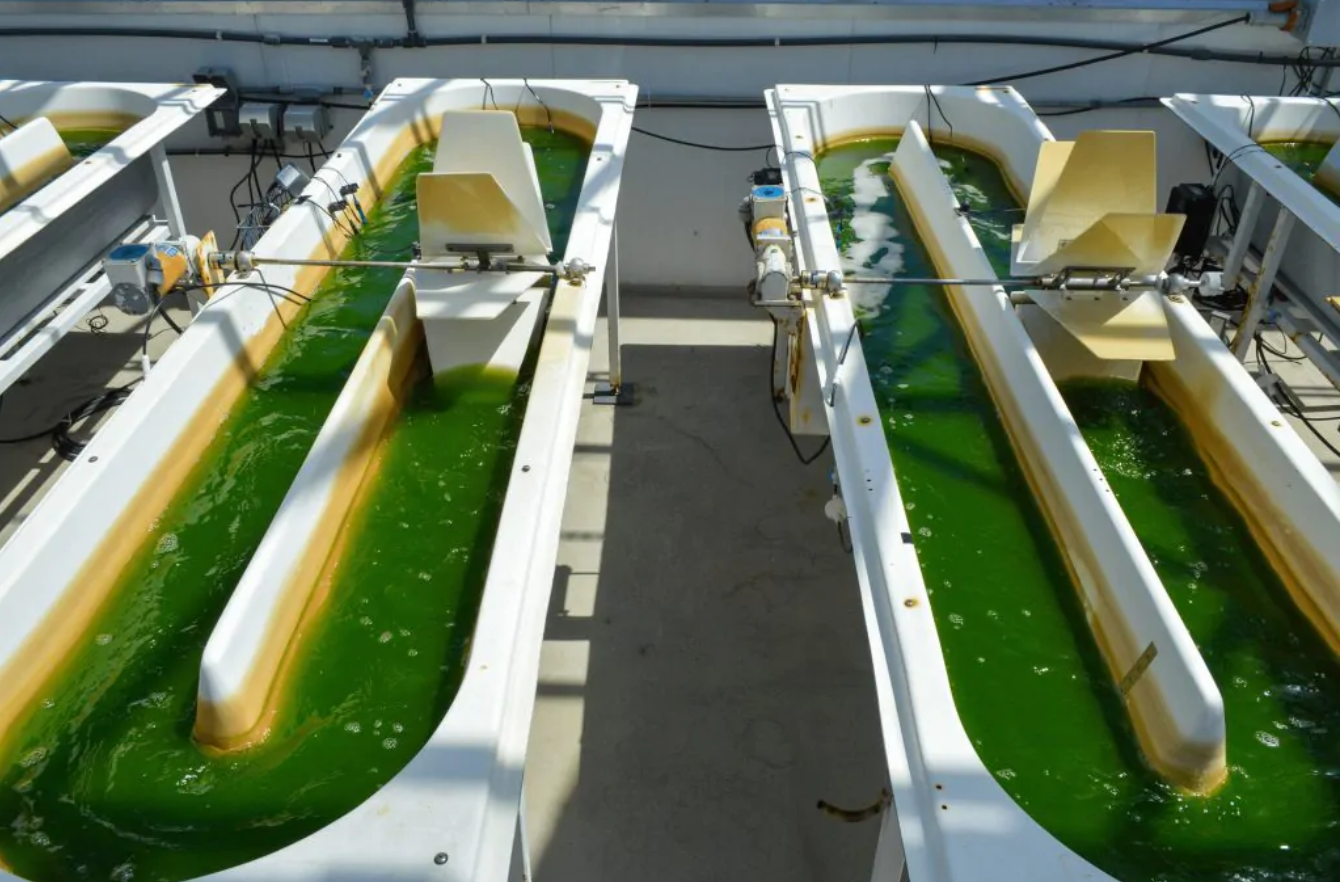

Viridos has created technology that can genetically engineer microalgae so that it produces lipids – a type of fatty acid – that generate oil in far greater volumes for use in both jet fuel and commercial diesel. The process utilises sunlight and CO2, and Viridos claims it cuts greenhouse gas emissions by almost 70% over the entire lifecycle of its use, while avoiding biomass grown on farmland or environmentally damaging alternatives like palm oil.

“This is a way to develop through a biological pathway that doesn’t compete with food,” Chang says. “It is in highly-controlled environments with CO2 and high salinity, in arid climates with access to those components to grow the algae, and so it’s a way to really leverage the biological pathway through mother nature to develop oils and feedstocks.”

The series A funding will come in handy for Viridos as the round comes after its biggest corporate partner, oil producer ExxonMobil, terminated a joint development agreement it struck with the startup in late 2021 following a decade of research conducted by the two. It’s a sign of the level of investment needed to make the technology commercially viable – several billions of dollars, several researchers in the field recently told The Guardian.

A company like ExxonMobil may have an interest in fossil fuel alternatives but ultimately will how much can it commit to costly long-time research when its core business is making so much money (it posted a $56bn profit for 2022) without regulatory insistence? Chevron did invest in this round but gave up its own work on algae fuels years ago and an earlier portfolio company in the sector, Solayzme, ended up filing for bankruptcy in 2017.

Airline carriers are on the user rather than the supply chain end, and it could be argued they have a greater need. United’s Viridos investment was the first out of the $100m Sustainable Flight Fund it launched last month with backing from the likes of Boeing and GE Aerospace, and Chang says it is seeking more investors.

“We expect to make three to six investments a year within the sustainable aviation fuel space,” he says. “That’s the target.

Algae are not the only route to sustainable biofuel. Fulcrum Bioenergy has created technology that derives jet fuel from household garbage and counts United and petroleum provider BP as investors, while LanzaJet has raised over $160m for a system combining bacteria with waste gas.

The challenge of algae-based biofuel is to make production efficient enough so that lower levels of water and energy are needed for the process, and while Viridos already uses seawater vessels instead of growing the algae in the wild, it plans to put the series A cash into making its technology more efficient before scaling it up to the point where it can be commercially feasible.

“It is already at seven times the productivity of traditional algae in the wild and they’re continuing to engineer it so it becomes even more productive,” Chang says.

“Then, once it hits a certain level, it will be able to achieve commercial scale and then we can begin looking at demo plans, ponds that can grow the algae at larger volumes for what we need.”

Lead photo courtesy of Viridos, Inc.