As India’s startup sector matures, foreign CVCs are increasingly choosing to set up teams in the country to invest in high growth sectors such as climate tech, fintech and software.

An important milestone was reached this year when India overtook China as the world’s most populous country. With a population of more than 1.4bn, India knocked China from the top spot, a position it has held since the 1950s.

In the venturing world, the Asian country also broke a record. In the first quarter of 2023, India had the second highest amount of venture capital funding of any country after the US, according to data provider Traxn.

India’s tech ecosystem is now the third largest in the world, notably overtaking China in 2022 for the total amount of venture funding. Last year was a bumper year for startup formation: 30% of all startups in India were created in 2022.

Corporate investors are swooping in to take advantage of India’s growth potential and its maturing startup sector. Several multinationals have opened offices in the country over the past couple of years and others have plans to form teams on the ground.

International corporate investors in India:

- Shell Ventures

- BP Ventures

- Intel Capital

- Amazon Corporate Development

- Nova by Saint-Gobain

- Goodyear Investments

- Salesforce Ventures

- Unilever Ventures

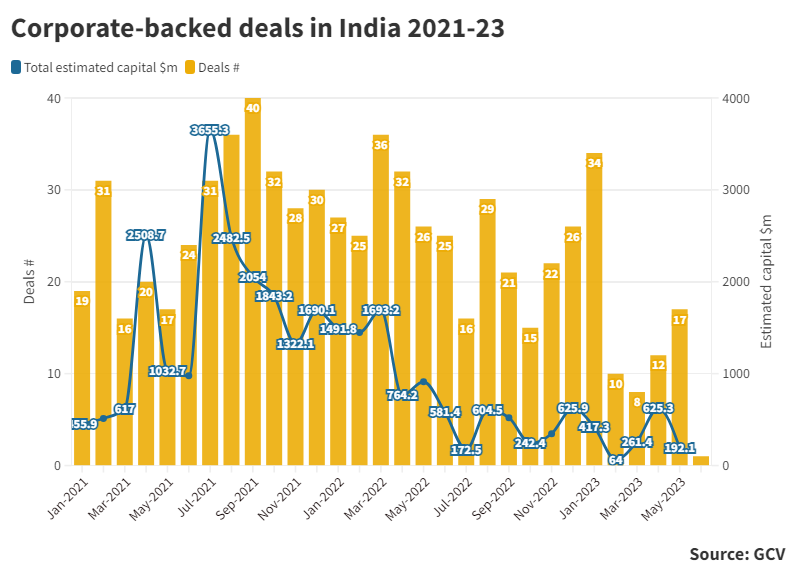

India’s startup sector is dominated by financial venture capital firms. But corporate investment is becoming a large part of venture capital financing. CVCs and family offices have participated in between 20% and 25% of all venture funding deals over the past five years, according to report by Bain & Co.

India is known for its e-commerce unicorn successes, such as online retailer Flipkart, founded in 2007 and majority owned by US retailer Walmart. Ola Cabs, a ride-hailing company, founded in 2010, is expanding globally.

But deep tech sectors are also attracting investment. India’s early-stage startup sector is maturing as universities such as The Madras Institute of Technology, IIT Delhi and the Institute of Science Bangalore churn out spinouts. The country’s network of accelerators and incubators, including CIE IIITH, Y Combinator and Venture Catalysts, has helped build up a startup ecosystem.

Bengaluru, Delhi and Mumbai dominate India’s startup sector, But so-called tier 2 cities such as Chennai and Jaipur are starting to create startup clusters, too.

We talked to three corporate investors in India to see what sectors they see opportunities in.

TDK Ventures

The investment arm of the Japanese electronics manufacturer opened an office in India in 2022. It is headed by Siddharth Mehta, investment director. Mehta previously ran Shell Ventures’ Indian office. TDK Ventures’ Indian team is still small with just two members and hasn’t yet announced investments.

The next generation of innovations in India is coming in mobility, says Mehta. Growth in this sector is partly driven by the country’s large e-commerce industry. A massive 350m people transact online, but this growth can’t be maintained without an effective way of delivering products, especially in last-mile delivery.

Mehta sees innovation in electric two-wheelers and three-wheelers, as well as electric motor and electric vehicle design.

Another area where he sees large demand is in battery chemical alternatives to lithium, such as zinc. Lithium is expensive as it is not domestically produced and is in high demand. Zinc is a much cheaper alternative.

But Mehta adds battery storage technology is still too expensive in India as the country does not have electricity grid off-peak tariffs when charging can be done more cheaply than during peak. “Unless you can monetise storage, the economics is challenging. Storage is important but it has to be cheap storage. Regulations have to change to make it economical,” he says.

Another area the investment team is considering is agtech. India has a shortage of agricultural labour as increasing numbers of people move from the countryside to the cities for better paying jobs. Technology solutions are emerging to enable higher crop yields and higher quality food production.

The unit is also exploring spacetech. “There are very countries in the world that can launch a satellite. India is one of them,” says Mehta. Launching a satellite in India costs between 20% and 30% of what it does in the US. “If you can make commercially viable satellite launches, you can do a lot of innovations in fuel for satellite launches and rockets. There are startups in India that are 3D printing rocket engines. You can have micro launches with smaller rockets.”

Sony Innovation Fund

The investment unit of the Japanese conglomerate launched operations in India in 2020 and started investing in 2021. It has done eight investments so far in fintech, healthcare and social commerce.

Social commerce refers to influencer-led online platforms which people use to market products and services. Platforms are usually connected to specific cities in India. The fund recently invested in a platform which influencers use to showcase beauty products.

Namita Raichura, an investor with the fund, says the unit invests in startups that have a strategic focus but also invests for financial return. “We invest from a strategic point of view but then realised we wanted to focus on the financial piece as well. That is when we looked at sectors that may have or not have synergies with Sony.”

Fintech lending is a large area of focus for the fund. Most Indians are underbanked and do not own credit cards. Startups have emerged that help to build up a credit-based sector, such as companies that derive credit scores. The fund also looks at health insurance technology as most Indians do not have health coverage.

Certain areas of fintech it stays away from because of regulations that make certain investments challenging. These include crypto, which is undergoing regulatory review.

Like elsewhere the economic downturn has impacted investments. Investors are less willing to pay the revenue multiples they have for the past few years and the fear of missing out isn’t there anymore, says Raichura. It is taking longer to close deals because of a mismatch between what founders expect valuations to be and what investors expect companies to be valued at.

Venture funding in India declined by 21% in the first quarter of 2023 compared with the fourth quarter of 2022, according to Tracxn. The number of funding rounds dropped 10% compared with the fourth quarter of 2022.

“We do have dry powder. But we have been cautious in what we invest in,” says Raichura. “We are not looking aggressively at the late-stage companies because we still believe there will be more correction in valuations.”

Times Bridge

Times Bridge is the strategic, global investment arm of media company The Times Group of India. Abhinav Bansal, who heads strategy for the CVC, says India’s rapid digitalisation at the consumer and business level offers massive opportunity.

“American CVCs were doing deals from global offices. But now they are opening Indian offices.”

“We have 850m active internet users, which makes us the largest open internet market in the world. The journey of converting passive internet users into paying and transactional-based users is becoming shorter and shorter,” says Bansal.

Enterprise technology is a particularly large opportunity, he says. Only 10% of India’s 65 million small and medium-sized enterprises do business online.

The investment unit welcomes partnerships with other corporate investors and has seen an uptick in international CVCs investing in the country.

Having a team based in India is critical to investing in the country, says Abhinav. Social customs mean it is essential to have a physical presence to build relationships with people. “American CVCs were doing deals from global offices. But now they are opening Indian offices,” he says.

He has noticed more Indian venture capital money now being directed to early-stage startups. Previously this money was mostly coming from international investors, he says. “The biggest change we are seeing is that even for really early-stage startups and small cheques, the capital was largely foreign; but now at these early stages there is enough capital in the country and investors. That is a big change.”

The Times Bridge fund traditionally invests in growth- to late-stage companies. But it is focusing more on early-stage startups in frontier technologies. “In emerging sectors – AI, climate tech, cyber security – most companies that will become big tomorrow are small today because the sectors themselves are very new. There we have started interacting with even series A companies,” says Bansal.

Prosus Ventures

The Netherlands-headquartered investment arm of the global consumer internet group is the most active corporate investor in India, according Tracxn data. Large Indian investments in its portfolio include Meesho, an online marketplace; DeHaat and Vegrow, both agtech services businesses; and Detect Technologies, a data processing company.

The unit started out primarily in business-to-consumer investments but has expanded in the past few years in business-to-business and software-as-a-service. It plans to expand investments across e-commerce, AI, fintech, mobility and logistics, agtech and sustainability, and blockchain, says Ashutosh Sharma, head of India investments.

“Given the early stages of the VC ecosystem in India, CVCs, in specific, and anyone in general who can bring strong domain knowledge to bare to the portfolio companies will be very appreciated,” says Sharma.