- News & Analysis

- Home

- Global Corporate Venturing

- Global University Venturing

- Latest News

- Publications

- Podcast

- The CVC Funding Round Database

- The CVC Directory

- Video

- Subscribe

- Newsletters

- Events

By Maija Palmer and Edison Fu

FEATURECorporate venture helps build Japan’s moonshot capacityJapan’s attempt to join the roster of nations that have landed on the moon ended in disaster in April. Tokyo-based startup Ispace came close to getting its Hakuto-R lander on the lunar surface, but the craft crashed on descent. An unflattering report by the Financial Times later raised questions about financial, technical and corporate turmoil at the company.

But while the failure may have bruised Japan’s space ambitions, looked at another way, Ispace is an encouraging story about the development of corporate venture capital in Japan.

The fact that an obscure startup founded in 2010 was in a position to attempt a moon landing at all is due to backing

from some of Japan’s biggest companies, from Sumitomo Insurance, telecoms provider KDDI, Japan Airlines, advertising company Dentsu and others. They were all investors in Ispace’s multiple funding rounds before the company listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange earlier this year.

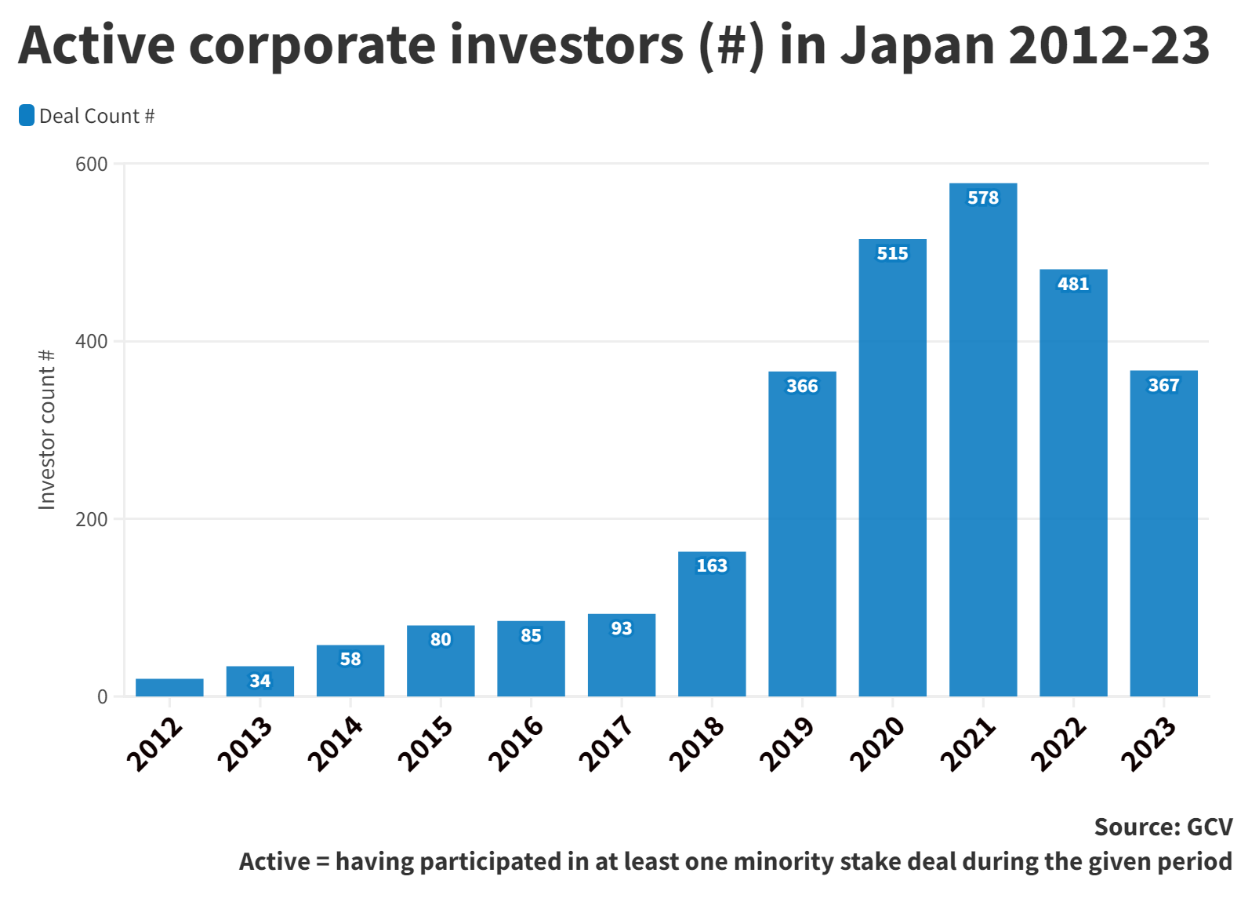

A decade ago, this would have been impossible, as Japan simply did not have the depth of corporate investor support. Back in 2013, only 34 companies — Japanese or foreign — invested in Japanese startups. In 2023 there have so far been 367 corporate investors backing the funding rounds of Japanese startups. Although the levels are down from the peak of the 2021 Covid-era boom, they are still more than 10 times higher than a decade ago.

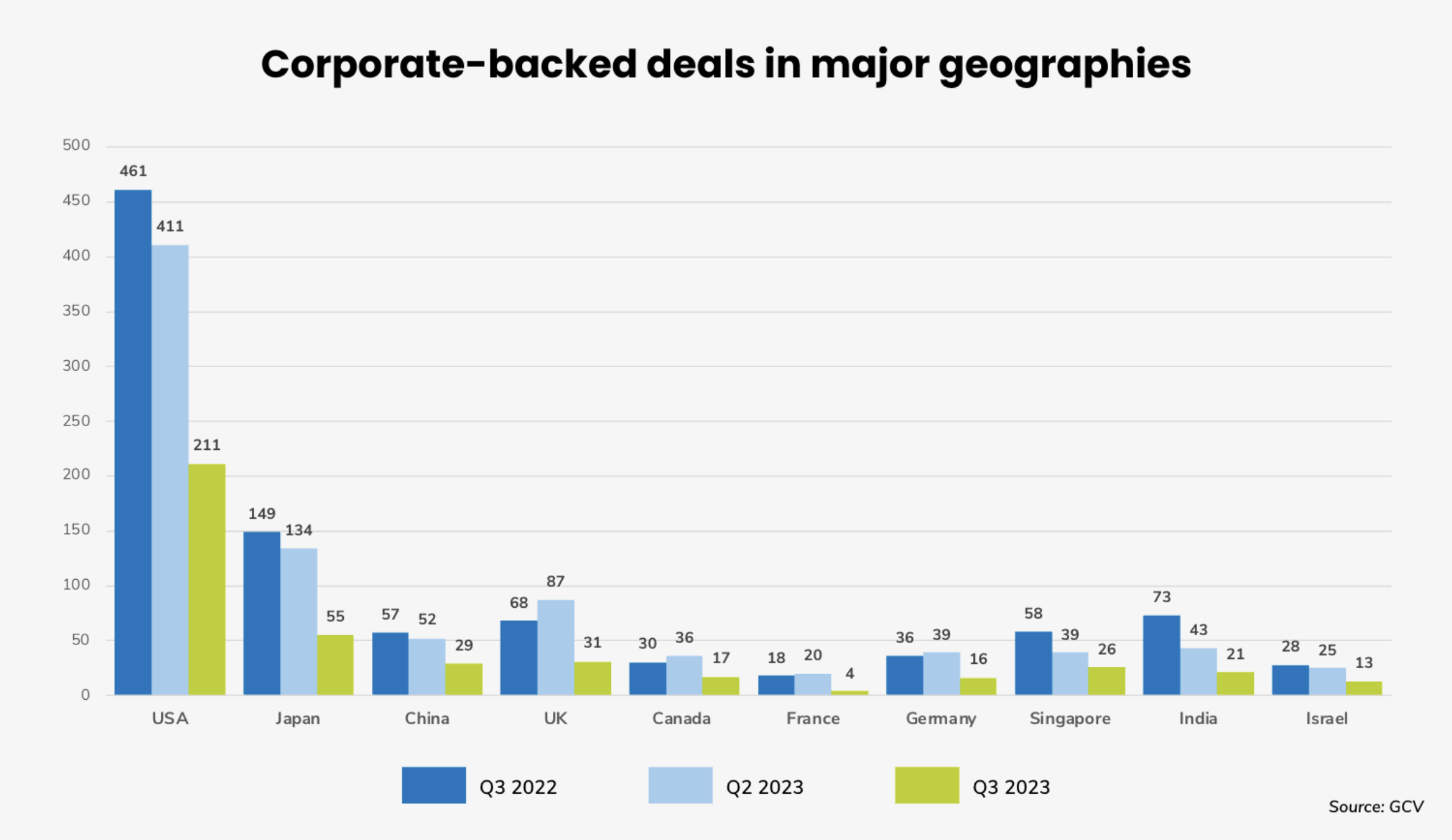

In fact, Japan has become the second most active country for corporate-backed startup funding rounds after the US.

Using venturing to access external innovation

Some of the bigger Japanese corporations, such as Panasonic and Sony, have had corporate investment operations going back to the 1990s, mainly based in the US. A number of Japanese companies, including Nissan, Hakuhodo, Itochu, NTT Docomo, have exposure to Silicon Valley innovation organisations such as World Innovation Lab, which invests in growth and late-stage US startups on behalf of Japanese partners.

The emergence of the Apple iPhone and Tesla as dominant forces in the mobile phone and automotive ecosystems was a wake-up call for many companies.

“Japanese corporates started realising they could not innovate enough by themselves. The also realised that to retain talent internally they needed to connect with startups. That’s why they started doing open innovation and CVC. I think that is a positive thing,” says Naoki Kamimaeda, head of European and Israel investment operations for Global Brain, a VC firm that runs corporate venture funds for more than 14 Japanese corporations, including names like KDDI, Kirin, Mitsubishi Electric and Tokyu Construction.

In addition to working through these partnerships Japanese companies are increasingly setting up their own corporate venturing units. Sony’s Innovation Fund, set up in 2016, has subsequently raised two further funds, bringing capital under management to more than $500m. The unit, which has more than 150 investments under its belt, has become so successful that it raised money for its third fund from external corporations in addition to Sony.

But even medium-sized companies, such as functional materials company JNC, are investing in startups. It is one of a number of Japanese chemicals companies that have set up venturing arms, including Asahi Kasei, Mitsubishi Chemical, Mitsui Chemicals and DIC. JNC does not yet have a dedicated CVC fund, but it has made some direct investments in startups from the balance sheet, a $4.5m investment in NanoGraf, the Chicago-based battery technology developer formerly known as SiNode Systems. JNC has collaborated with NanoGraf using some of JNC’s technology, and JNC has helped the startup commercialise its products.

JNC also has a long-standing LP investment in Draper Nexus Ventures, a US investor in early-stage startups, which helps it get exposure to ideas emerging in Silicon Valley.

“Our company made an LP investment in Draper Nexus Ventures when it was founded in 2011, and its strength lies in its over 10 years of experience,” says Kazutoshi Miyazawa, director and managing executive officer of JNC. “Although we have not yet formed a CVC unit, we leverage this strength when we invest directly in startup companies.”

A dedicated CVC unit may be something JNC considers in the future, Miyazawa says.

Kamimaeda says that many Japanese corporations conserved a lot of a cash as a security measure after the financial crisis of 2008 but are coming under increased pressure to spend these reserves. This has been another factor fuelling the founding of corporate venture funds.

The success of funds like Sony’s or even SoftBank’s $100bn Vision Fund, have also shown what is possible and persuaded many companies that they too need an investment vehicle.

“Always in Japan, so there is our peer pressure or kind of FOMO (fear of missing out), so that’s one of the levers,” says Kamimaeda.

Focus on domestic startups

While many Japanese corporate venture units still look to Silicon Valley, more recently there have been venture operations set up to focus on investments in emerging markets such as India or Africa. Mobile entertainment company MIXI created a $50m fund to invest in India and Sony just created a $10m fund to invest in Africa.

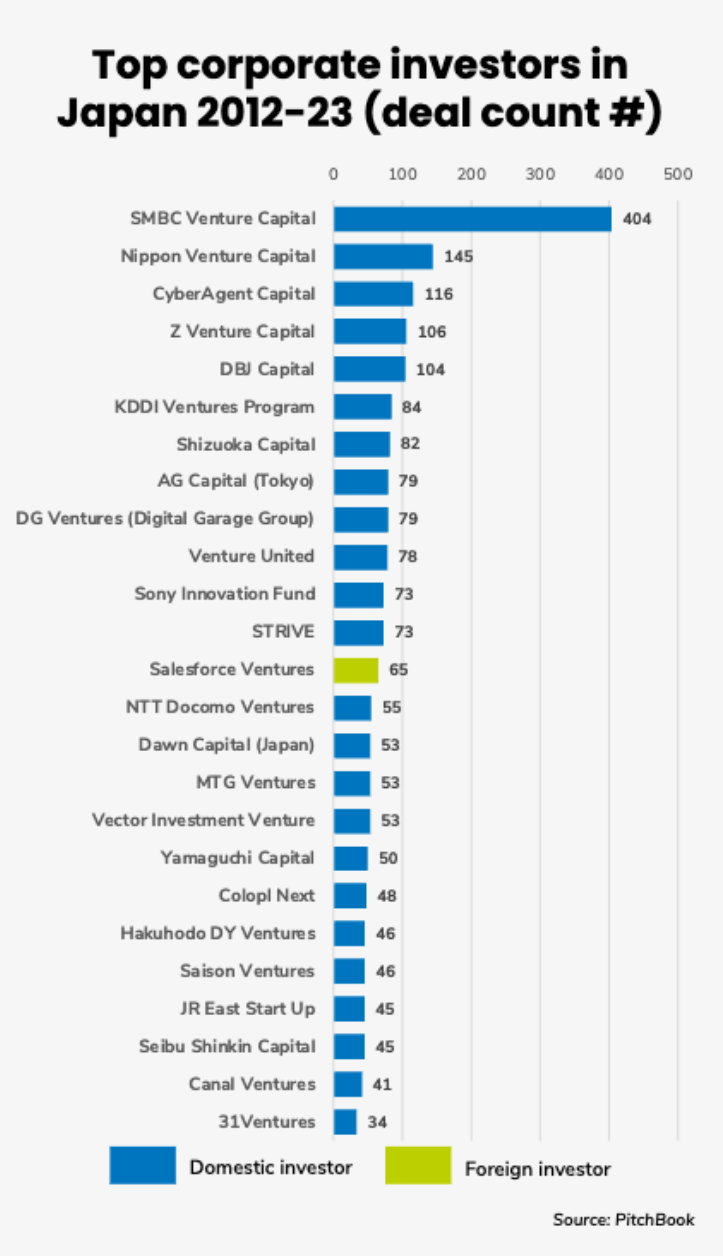

Most Japanese corporate venture investments, however, go to Japanese startups. The top corporate investors in Japanese startups in the past decade have all been Japanese companies, with the exception of Salesforce Ventures.

We recently surveyed some 50 Japanese corporate venture units as part of the Keystone Global Venturing survey and found that investment priorities among this group was heavily weighted towards domestic investment in Japan.

Young units and small funds

Most Japanese CVC funds are still relatively young and the fund sizes are small. A majority are still less than four years old, and are in what we call the “startup phase” in terms of maturity.

Gen Tsuchikawa, chief executive and chief investment officer of Sony Ventures Corporation, says getting over this initial phase is still the biggest challenge for Japanese corporate venture units.

“Same as global CVCs, many need to get over the first three or four years to continue to survive,” he says.

A majority of corporate venture teams have less than $100m in their current fund — with the largest number of funds operating under the $50m mark.

One Japanese corporate investor who preferred not to be named said Japanese funds were starting small because they are still finding their feet. “The startup industry in Japan is relatively young. The reality is that we have few professional talents. More US venture capitalists are experienced in famous startups, like GAFAM, or entrepreneurs than in Japan. This is the reason why they launch the funds conservatively,” he said.

Nevertheless, Japanese funds are set up with a relatively independent structure — more than half are set up as a separate legal entity with fully committed capital.

This independence may not be all it appears, says Global Brain’s Kamimaeda. While the structure may be independent, most funds will have very close ties to the parent company, with much of the key personnel coming from there. This keeps the funds closely aligned to the business priorities of the large corporate, says Kamimaeda.

“There is always a parent company representative on the board and they will be the ultimate decision-makers. They may have a separate organisation but they are still staffed by internal individuals, so they are not really independent,” he says.

This close alignment with the parent corporation was apparent also when we looked at the financial goals of Japanese CVC units. Most units are not aiming at VC-level financial returns. Nearly half have no financial target at all, or are simply aiming not to lose money.

“Aiming only for financial return wouldn’t actually make sense,” says Kamimaeda, especially in the case of these small, still somewhat experimental funds. “$50m or $100m from a large global Japanese corporation is not that meaningful compared to its balance sheet,” he says. Therefore, the investment rational tends to be predominantly about strategy.

However, another investor, who prefers to remain anonymous, says this kind of thinking may be overly cautious and could end up holding companies back.

“This is typical Japanese thinking: invest to avoid failure,” he says. “In the venture capital investment world, it is a 1-win, 99-loss approach, and a fund is successful if it can generate even one moonshot return. We need to learn more about these industry practices from the U.S. market and change how we think about risk money. When businesspeople who are not founders think about new businesses, they tend to think in terms of avoiding failure instead of thinking of creating a large business. I believe this needs to be significantly improved in the industry,” he says.

There is an expectation that Japan’s corporate venture culture will become less cautious as time goes on. Some of the earliest

corporate funds, created in the period between 2012 and 2015 are now coming to the end of their 10 years of operation.

“Then we will have experienced fund managers and capitalists with track records in the market. Therefore, we will see sizable funds debut soon,” he says.

Setting up for new moonshots?

Japan also has a lack of angel investors for early-stage projects, says Miyazwa of JNC. Having more experienced investors and serial investors in the ecosystem as early corporate venture funds finish their first cycle could help address that.

Attitudes towards startups are changing too, says Kamimaeda. Post-war Japan may have been characterised by a jobs-for-life at large corporations, but every year more people working at startups, says Kamimaeda. “Every year that number more than doubles,” he says “It is from a small base but I think gradually it’s getting there.” Ten years from now, Kamimaeda predicts, it will feel much more natural for people to pursue careers in startups.

Tsuchikawa at Sony says there is no reason Japan’s corporate venture sector couldn’t double over the next decade.

Although Japan’s moon ambitions — and the Ispace moon lander — may be in pieces over the Atlas crater, the company did manage to land $52m on Tokyo exchange’s growth market in April. It unveiled a new lunar lander in September , which will make a new attempt at a moon landing in 2026.

Every space programme is littered with failures. SpaceX’s Falcon rockets went through three launch failures in a row before managing a first successful take-off. The US space programme’s Atlas rockets in the 1960s had an alarming 50% rate of failure in test flights before they managed to get astronaut John Glenn into space.

Even outside of space flight, the failure rate of startups is somewhere close to 90%. The trick is to have enough attempts to get that one moonshot success, and a robust corporate venture capital base is part of what is needed to build that.

Healthcare | Human microbiome

Publications | Reports | GCV

Read the full report on your tablet or device.Download PDFAbout us

GCV provides the global corporate venturing community and their ecosystem partners with the information, insights and access needed to drive impactful open innovation. Across our three services - News & Analysis, Community & Events, and the GCV Institute - we create a network-rich environment for global innovation and capital to meet and thrive. At the heart of our community sits the GCV Leadership Society, providing privileged access to all our services and resources.

Navigation

test reg

test regLogin

Not yet subscribed?

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish.Accept Read MorePrivacy & Cookies PolicyPrivacy Overview

This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. But opting out of some of these cookies may affect your browsing experience.Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.