GV helped head up a 35-strong investor network backing Curie, which has raised $520m to bring CVC-like strategic help to its seed-stage drug developer portfolio.

Curie.Bio launched this week with $520m from investors including internet and technology group Alphabet’s GV unit, which looks to be leveraging its life science experience to participate in a new approach to healthcare startups.

A first-time venture firm raising above $500m is extremely rare but it is a measure of both the expertise of its founders and a vision which combines early-stage investment with close coaching, to some extent amplifying what traditional corporate VCs offer.

The US-based company invests $5m to $7m at seed stage but it also promises to act as the ‘drug discovery co-pilot’ for startups, working closely on selecting drug targets, hiring and data evaluation before helping them with the nitty-gritty of raising series A funds.

Two of the firm’s three co-founders come from healthcare venture firm Third Rock Ventures while the third, CEO Zach Weinberg, has two years at Alphabet on his CV from back when it was still known as Google.

All three are also serial co-founders of pharmaceutical developers, with Flatiron Health, Celsius Therapeutics, Relay Therapeutics and Foundation Medicine on their CVs, all four of which were exits for GV, and Curie claims its overall team has helped take more than 60 drug candidates into clinical trials.

In some ways, the approach mirrors the expertise early-stage drug developers can get from corporate venturers who have access to experts from within their own companies. But Curie ramps up that element by offering a network of contract research organisations (CROs) and back-office partners along with contracting, alliance and project management services.

In theory, that means founders, especially those without company-building experience, can afford to spend less time on organising the corporate side and more on lab work.

The firm has named Forward Therapeutics, a developer of small molecule immunology drugs, as a portfolio company together with multiple sclerosis therapy developer Astoria Biologica and Decrypt Biomedicine, a protein-focused startup still in stealth.

In contrast to the Curie team, the startups seem to have been launched by founders coming from university research positions or roles at corporate pharmaceutical firms, with none having experience working at this level.

What Curie can do is fill in the gaps a strategic investor would without taking the big stake of a full-time co-founder or bringing the crossover interest of a large corporate.

GV is one of the most prominent Curie backers but it’s part of an investor network which also features drug discovery and development company Evotec and Leaps by Bayer, the investment arm of drug and chemicals producer Bayer, in addition to more than 30 VC firms – some healthcare specialists, others not.

The VC firms are understandably attracted to the Curie concept because of its potential to reduce risk in an industry where 90% of therapeutic candidates fail even if they reach clinical trials.

The corporates on the other hand get to boost their networks by getting early insights into some of the most promising life sciences startups, in GV’s case through an investor staffed by people with whom it has already worked.

None of GV, Leaps or Evotec are active life sciences investors at seed stage, though GV in particular has made some huge commitments at series A. Having a backer that can transfer high-level strategic assistance before they invest may turn out to be a difference maker by the time they come on board with their own expertise.

As Astoria co-founder Tim Vartanian says on Curie’s website, his team could already take charge of choosing therapeutic targets, preclinical experiments and clinical proof-of-concept studies, but it did not have experience creating a strategic business plan, choosing CROs, preparing a drug candidate for regulatory approval or their company for series A fundraising.

“The things we didn’t know how to do, the Curie team had done a hundred times over effectively,” he says. “The things we did know how to do, the Curie team helped us do better.”

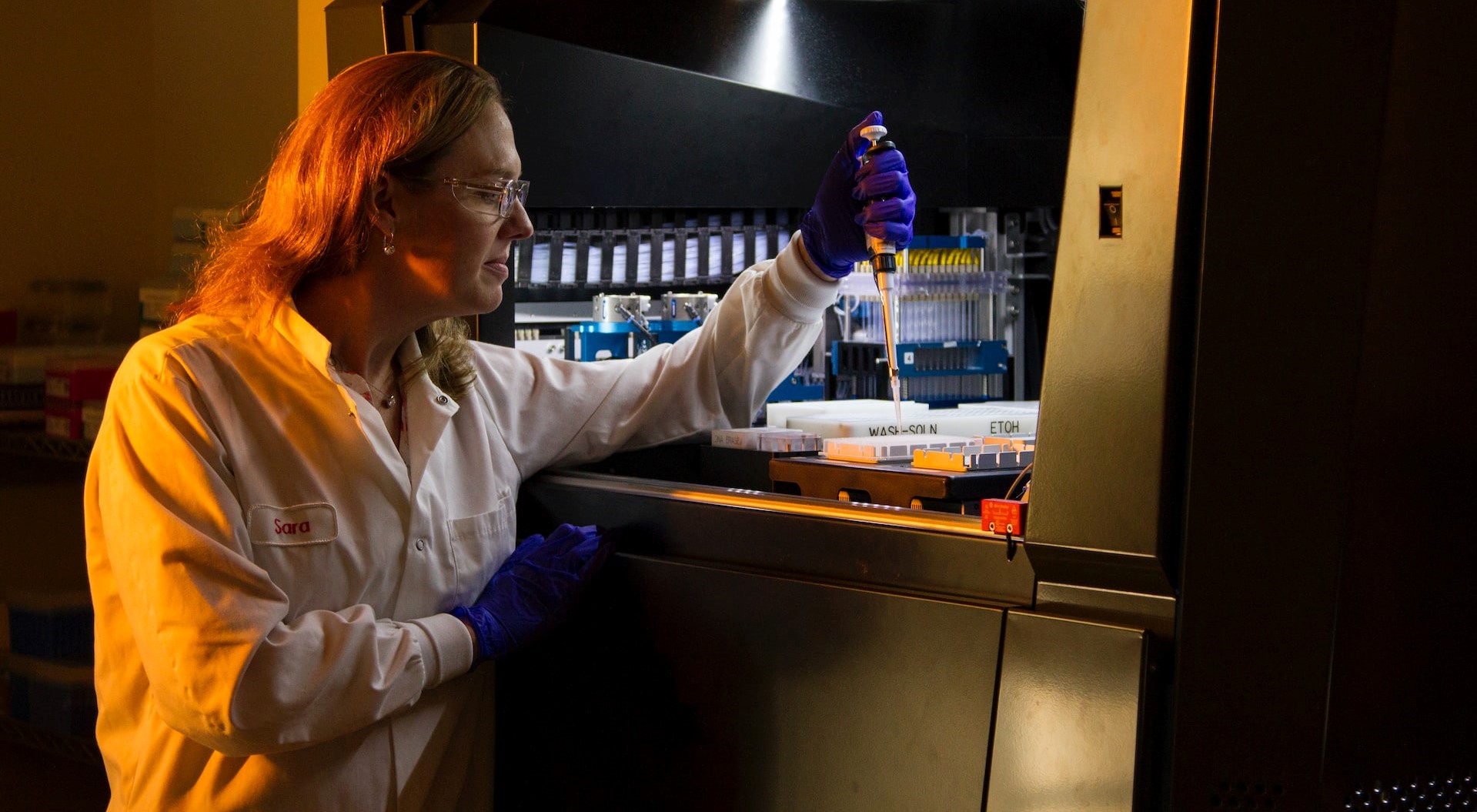

Photos courtesy of National Cancer Institute via Unsplash