Brazil's corporate venturing units are mostly less than 3 years old but have been set up in a way that maximises chances of success.

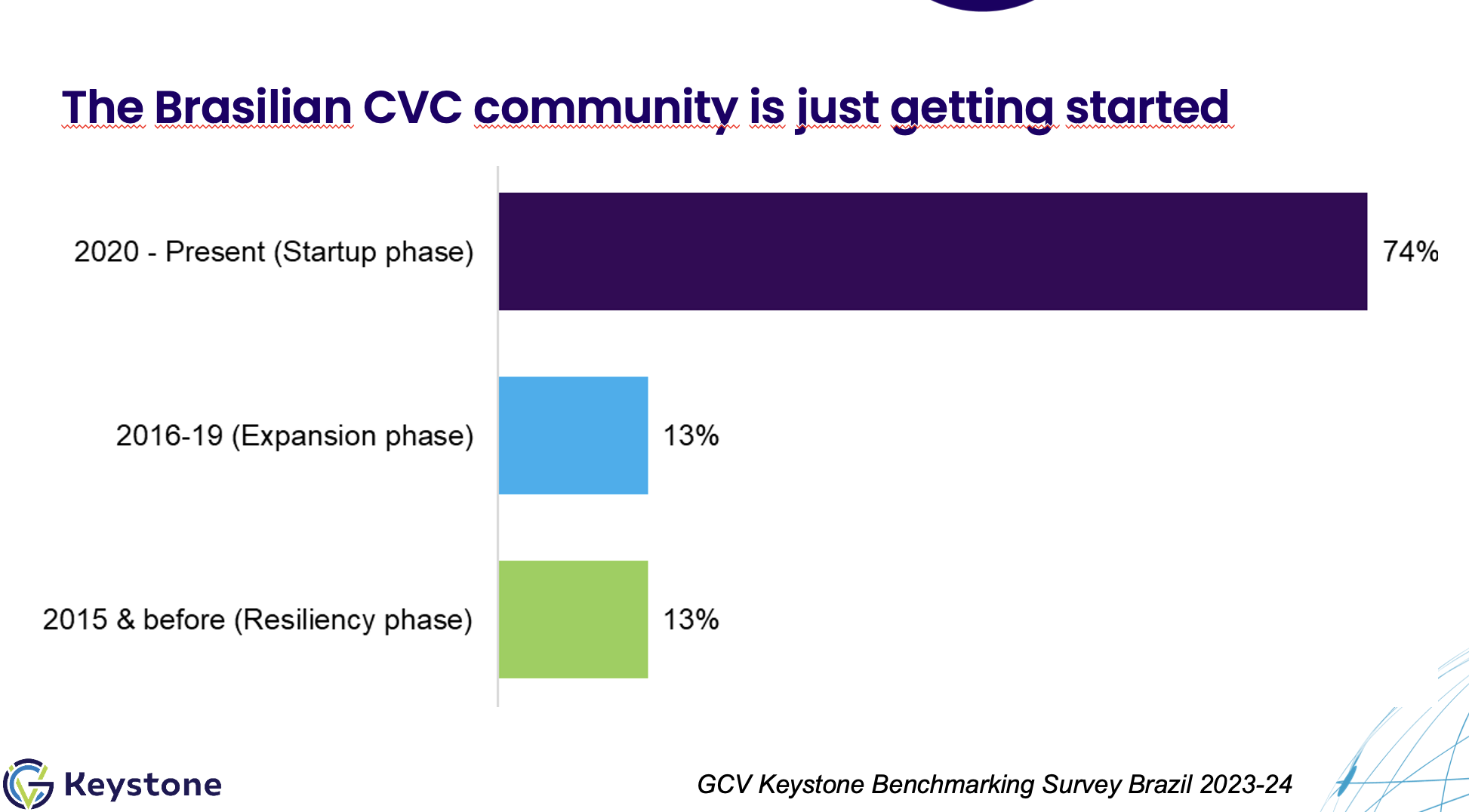

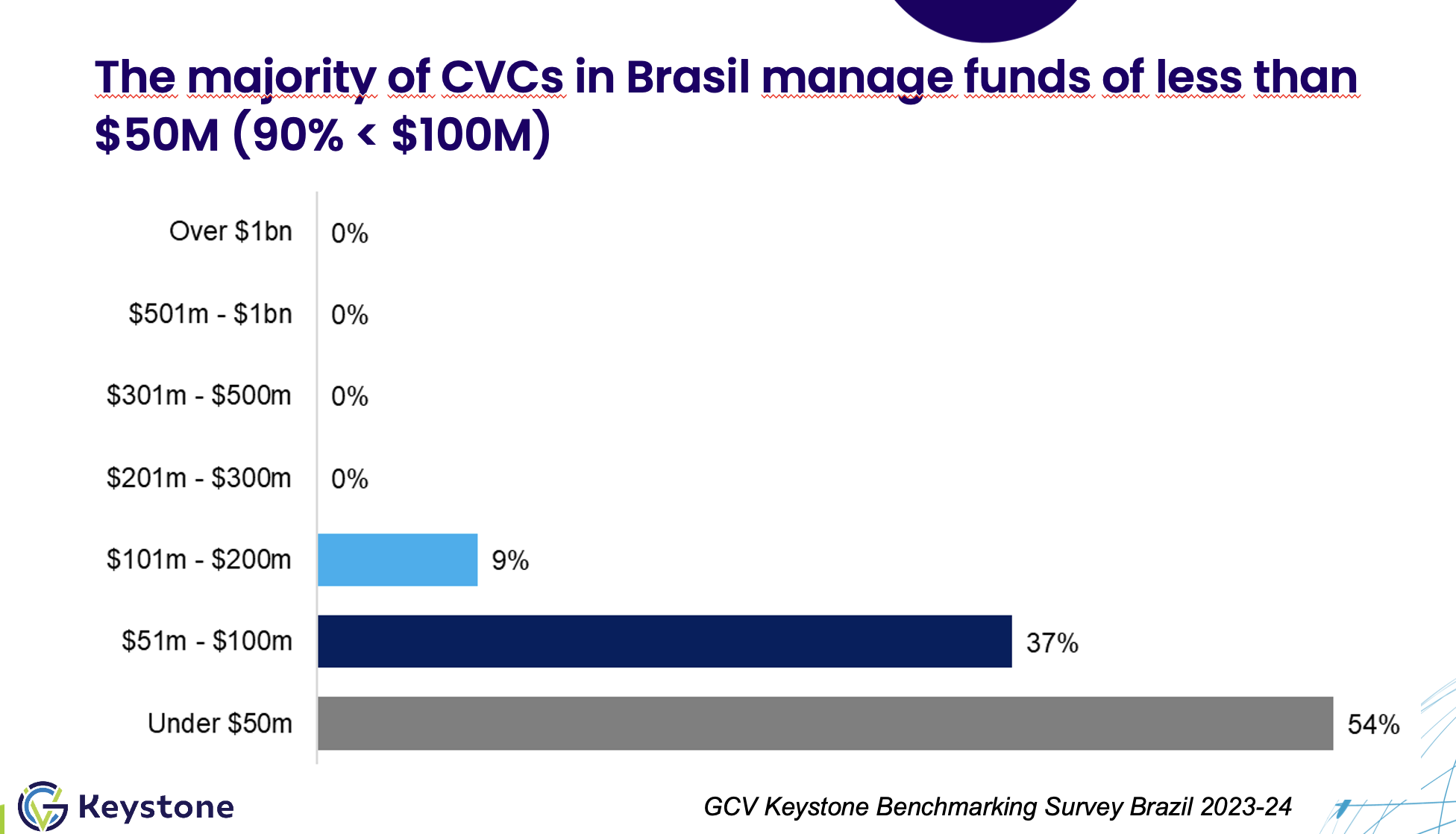

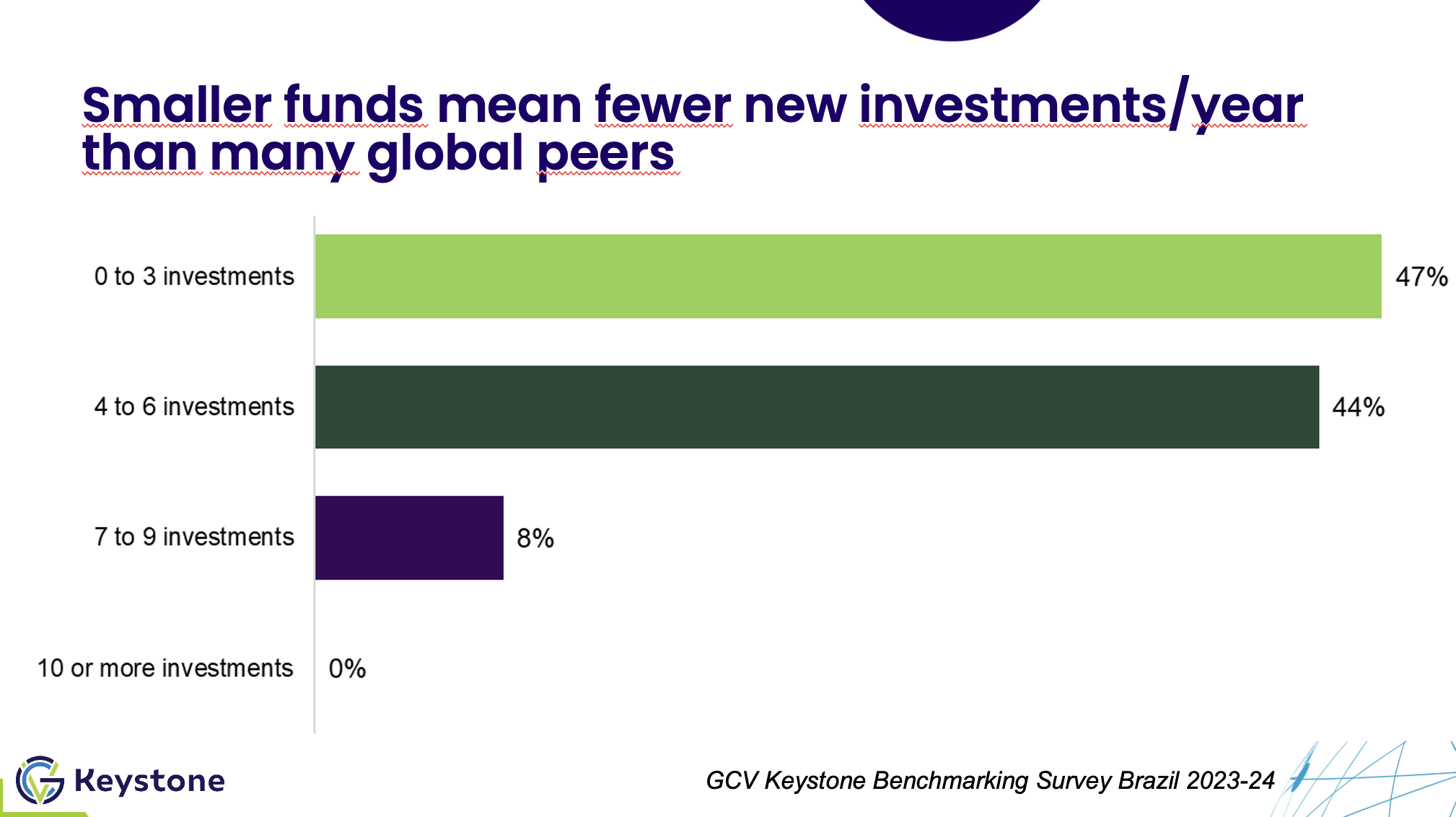

Brazilian companies have only very recently begun to set up corporate venturing units to invest in startups. Most CVC units have been set up in the past three years and the funds are still relatively small — a majority have less than $50m. Each fund makes just a handful of investments each year.

But corporate venture capital is already playing an outsized role in the Brazilian startup economy. Some 59% of all startup funding rounds in the country included money from corporate investors.

So what do Brazilian corporate venture funds look like? How do they operate?

As part of our annual GCV Keystone benchmarking survey of corporate venturing, we surveyed Brazilian CVC units specifically, and have so far had around 50 responses. Although the survey is still ongoing, we’re giving you a flavour of the findings so far. This is just nine out of more than 50 findings in the full report, but this already begins to build a picture.

Though young, Brazilian CVCs appear to have been set up for maximum chance of success, with independent structures, VC-like metrics and preparation for follow-on rounds. They appear to be avoiding some of the problems that have tripped up CVC teams in other regions.

The survey runs until 15 November. If you haven’t already added your data to this, you can take part here. All respondents will receive the full copy of the report.

1. Most Brazilian corporate venture funds are less than 3 years old.

2. As a result, the funds tend to be small, with almost all of them having less than $100m in capital. This is fairly typical for the first fund set up by a company. In a few years we would expect to see corporate venture units begin to raise their second funds, and these will typically be double or even triple the size of the initial capital allocation.

3. Small funds can only make a few investments a year, especially if they are reserving a portion of the capital for follow-on rounds.

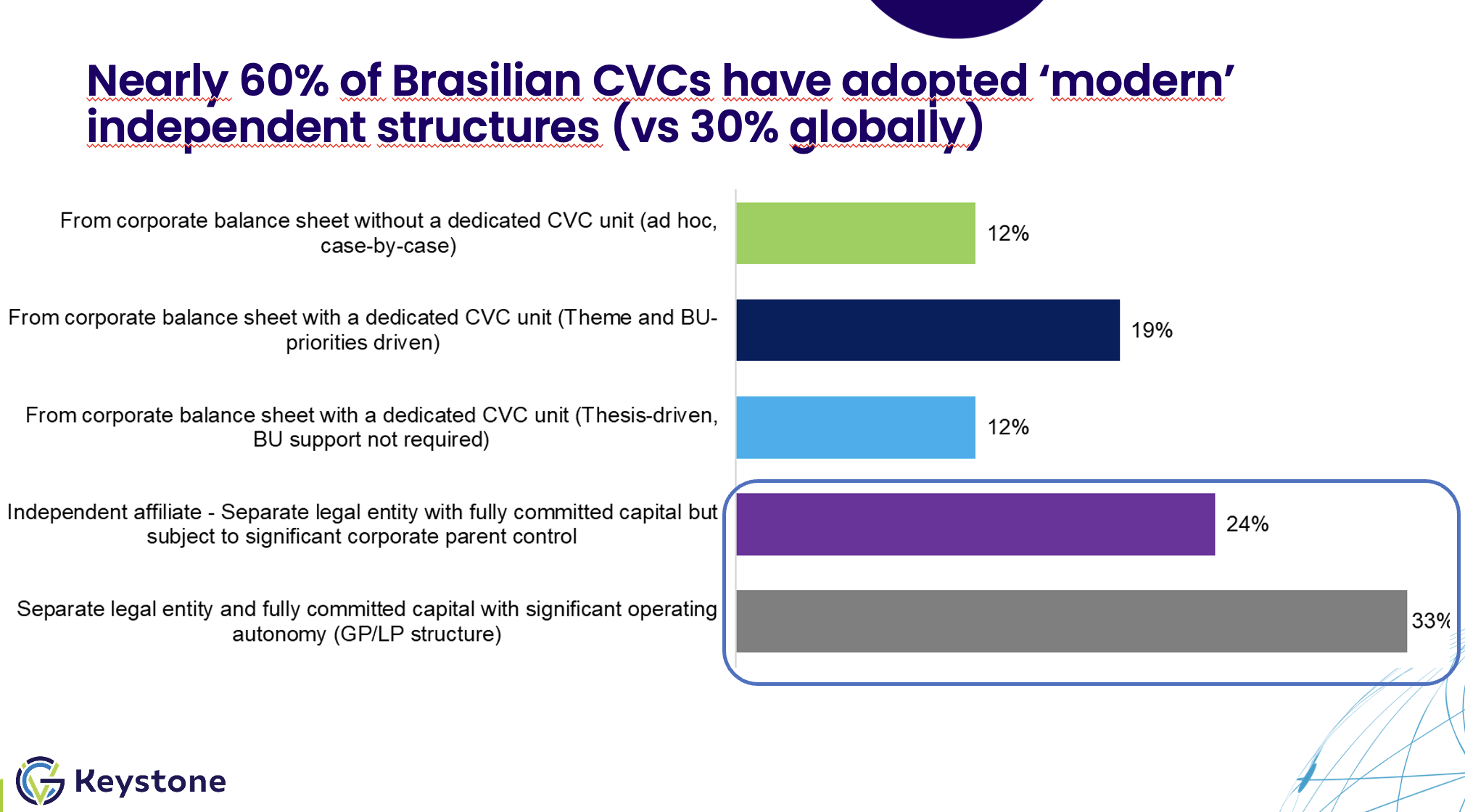

4. Most Brazilian funds are set up as independent legal entities. This is a change from the typical development of corporate venturing in the past, when companies would often start with more ad hoc investments from the balance sheet before moving on to set up a dedicate fund. It is interesting that many Brazilian companies seem to be skipping that ad hoc stage.

Independence can give corporate venture units some advantages. They can often act faster on investments and aren’t at risk of having their budget cut as the parent company’s strategic priorities change.

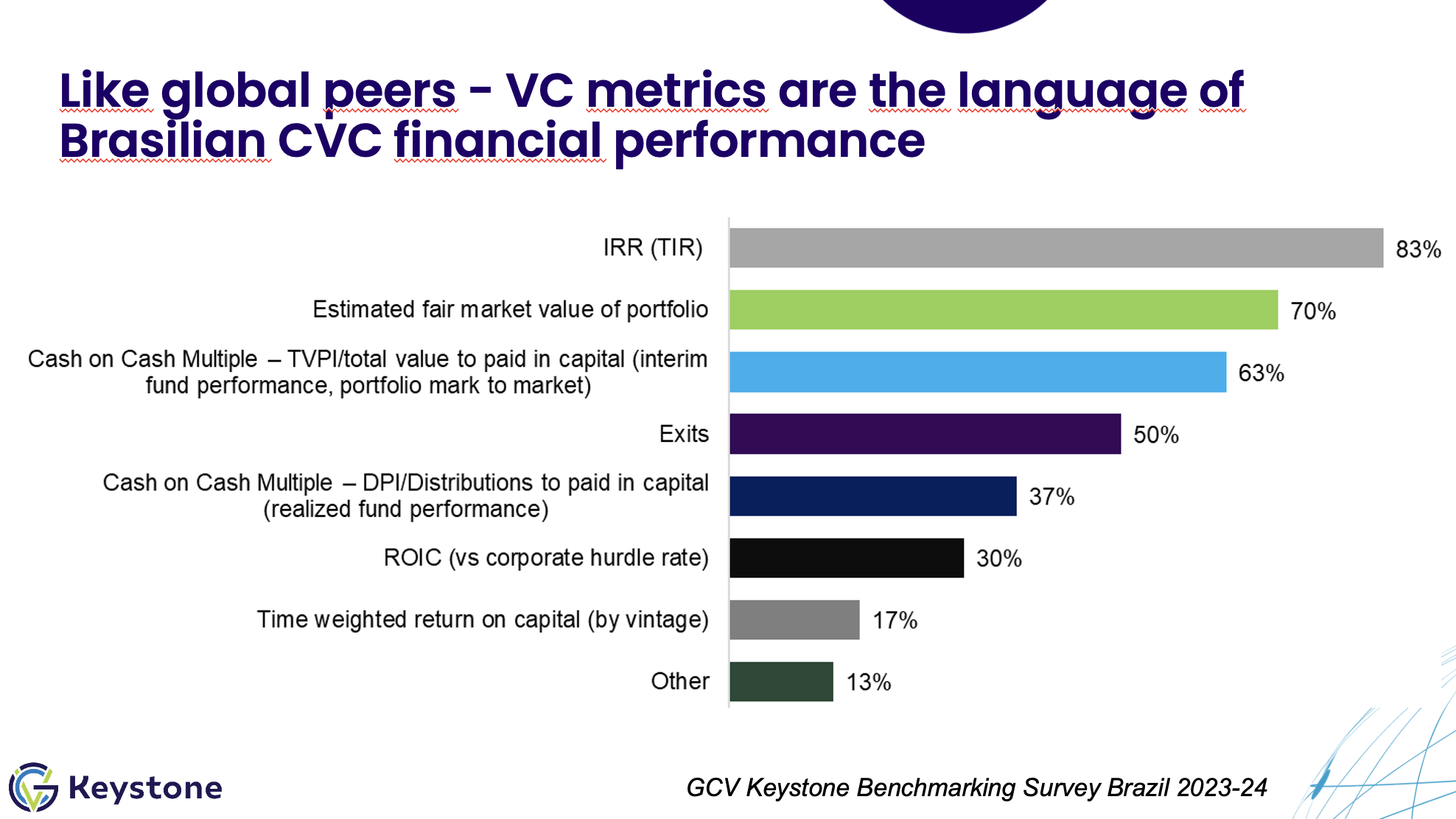

5. Brazilian CVC units use VC-like metrics to assess their financial performance. This is in line with what we see globally.

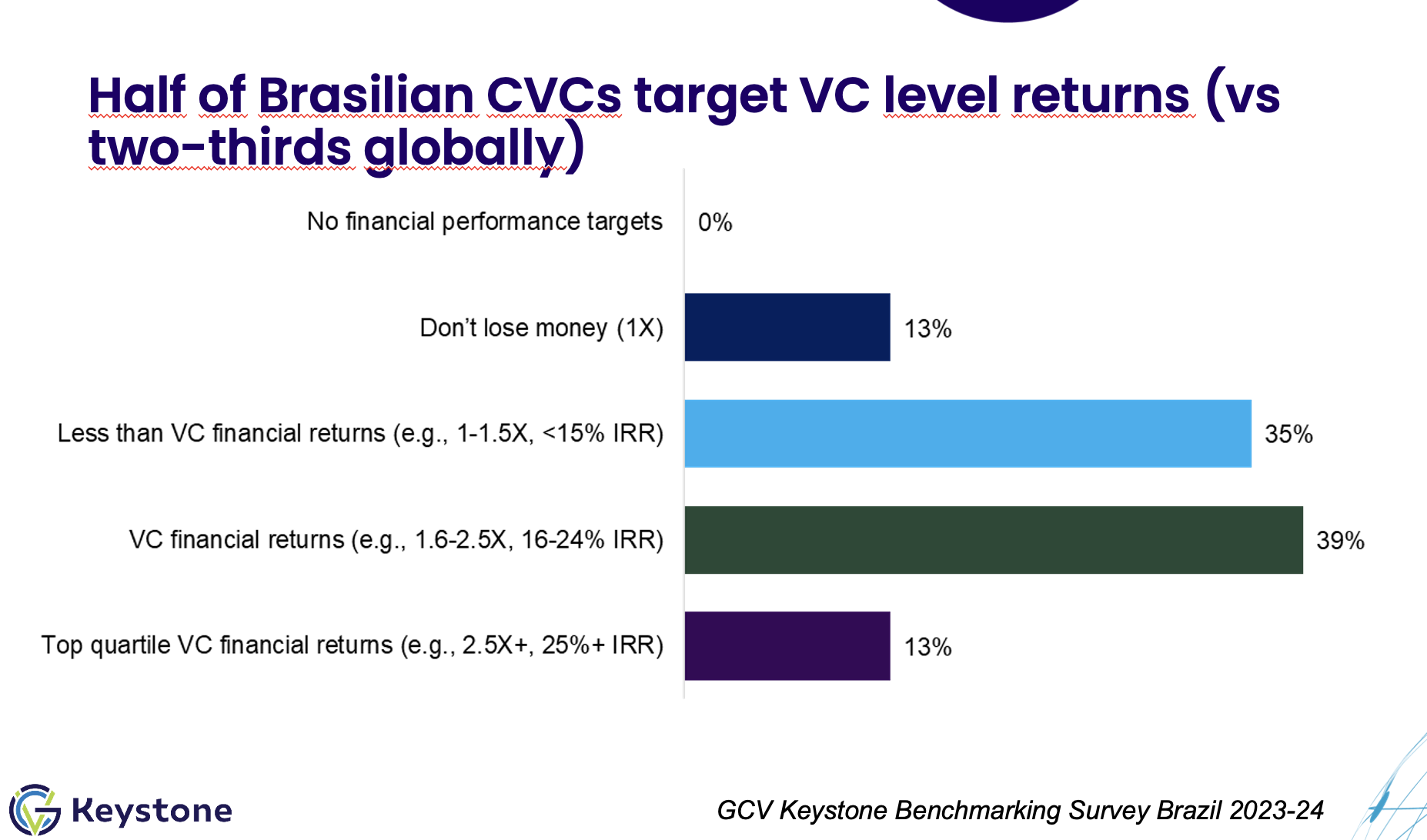

6. However, Brazilian CVCs are a little less likely than their global peers to be targeting returns at the same level as VCs. Nearly half are aiming just to not lose money or to make a small return. The strategic benefits of investments would be much more of an incentive than financial performance, which is to some extent natural for corporate investors. This is especially true in the early stages of funds, when the investment activity is more about learning and exploration.

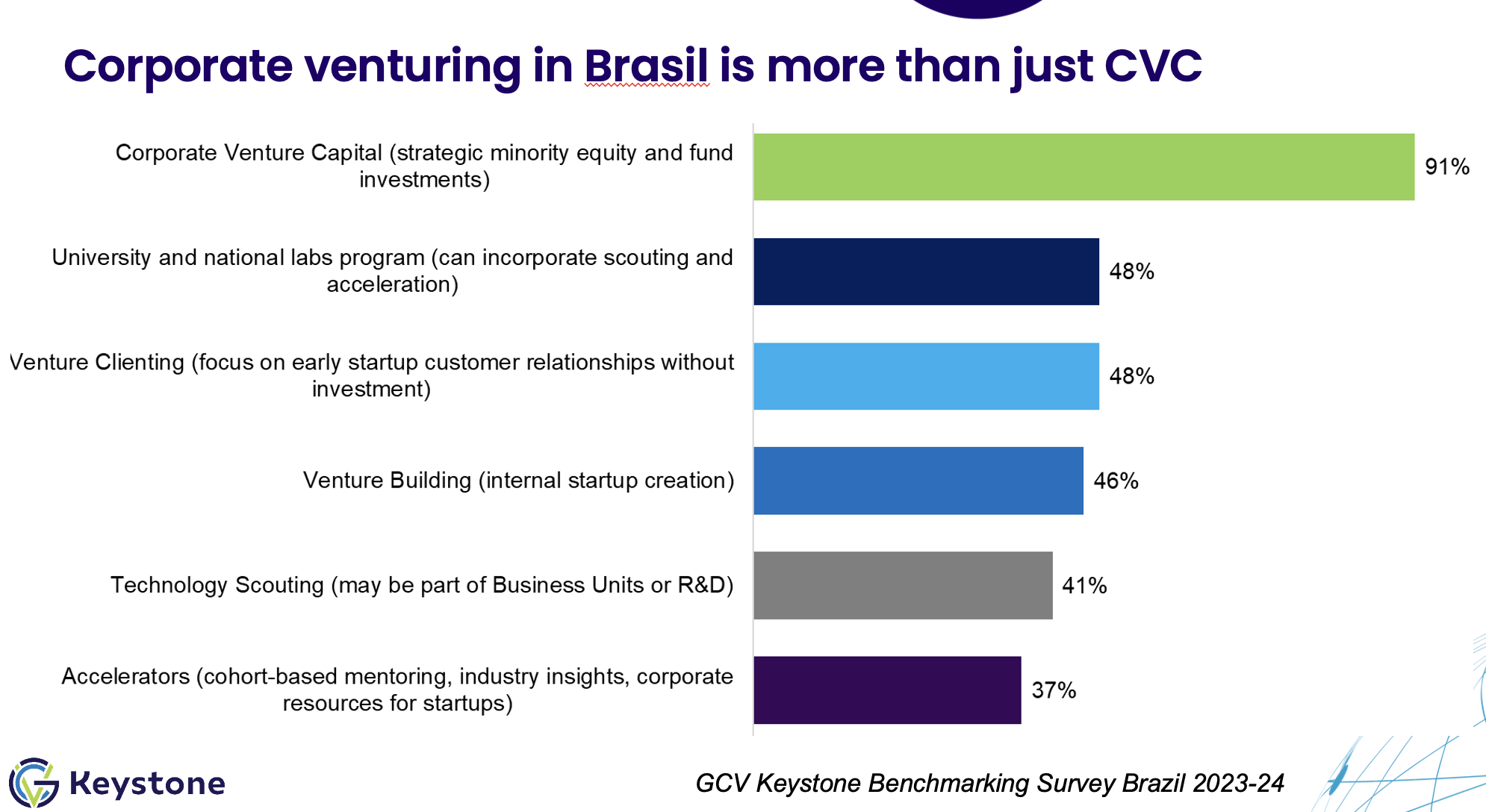

7. Brazilian corporate investors use a variety of tools — not just equity investment in startups but also building their own startups internally, working with universities and labs and venture client programmes where they take on young startups as suppliers.

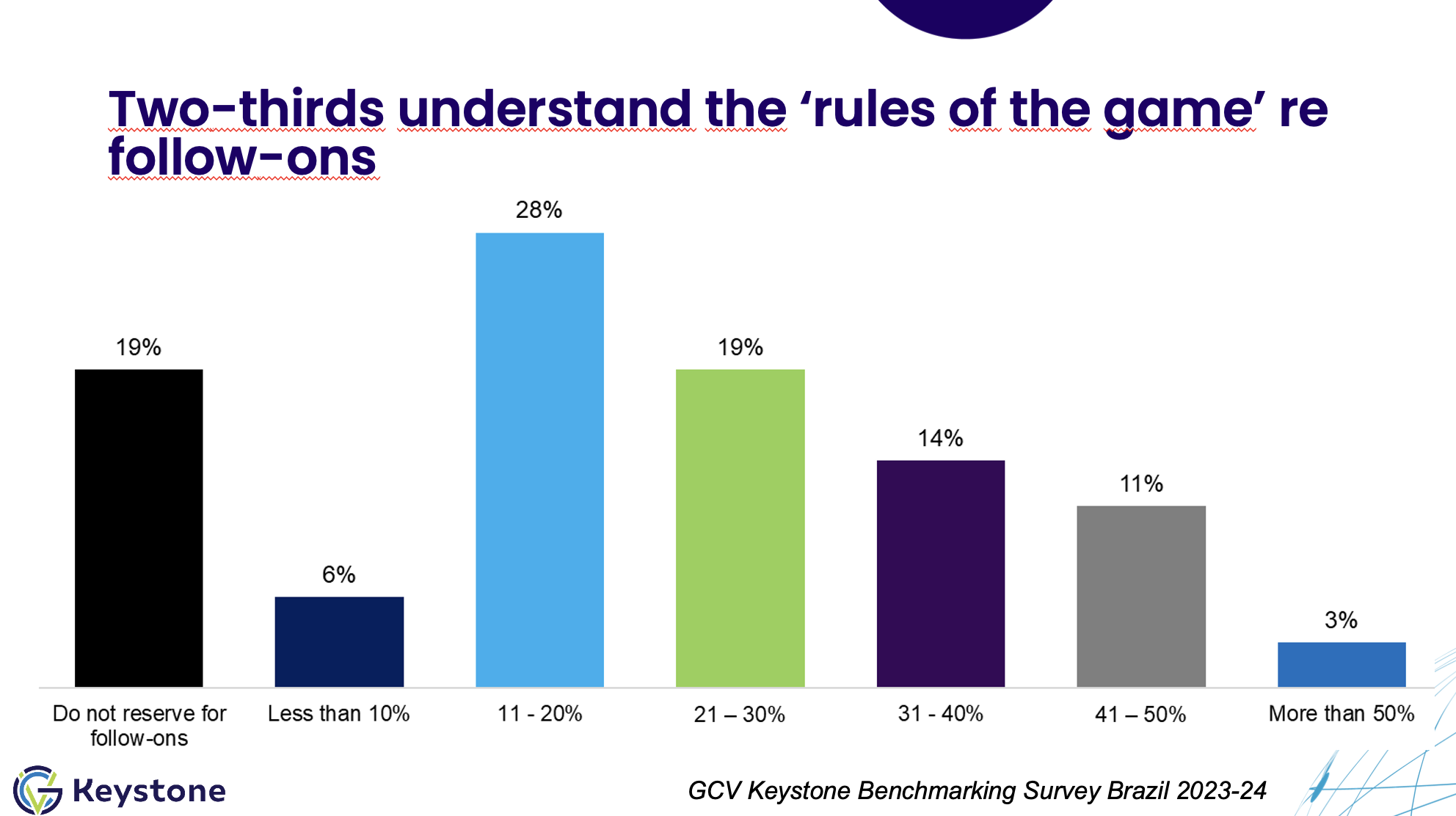

8. Corporate investors sometimes make the mistake of not reserving enough of their capital for follow-on rounds for their portfolio companies. This doesn’t seem to be the case in Brazil, where a majority of CVCs tell us they are reserving at least 20% of the fund for future support.

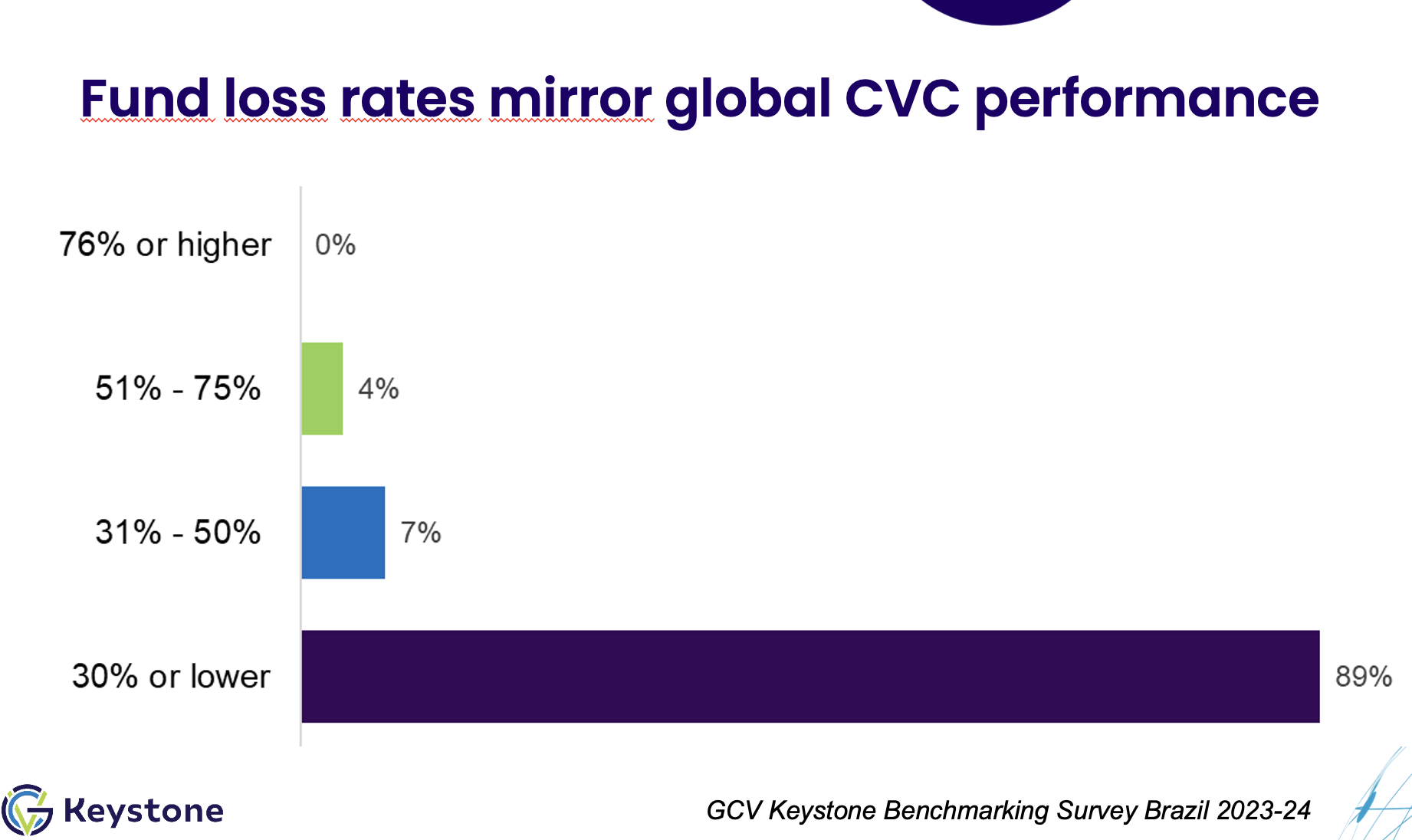

9. It is still too early to tell how well the new crop of Brazilian CVC units will perform, but so far their reported performance is in line with global trends.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).