Climate change is creating mounting insurance losses every year, creating a near-existential crisis for the industry. Can tech help?

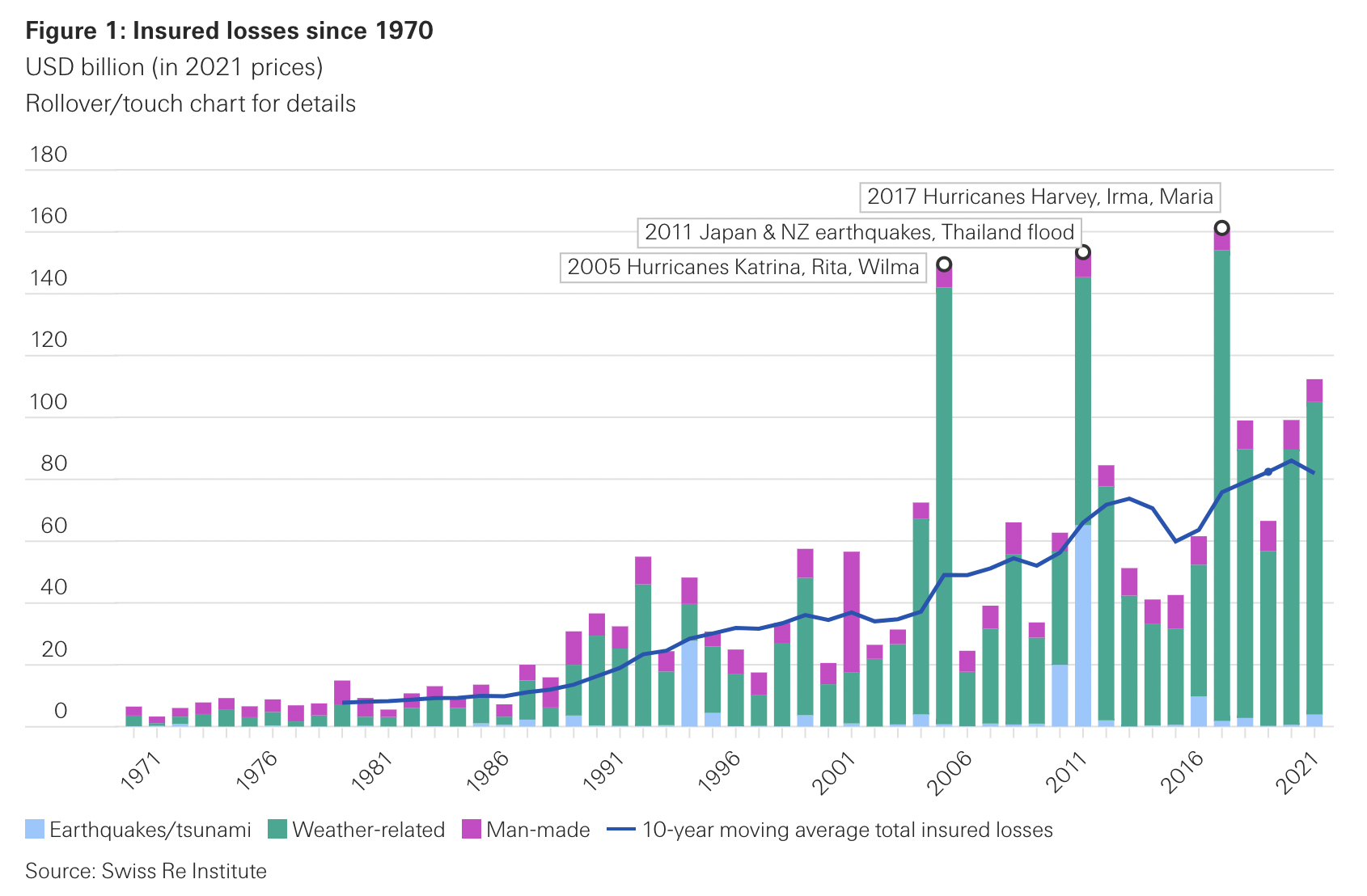

Last year, natural catastrophes resulted in a total global economic loss of $270 billion according to reinsurer Swiss Re. The general trend over the past few decades has been for insured losses to increase between 5% and 6% each year. Much of that increase has come from weather-related events such as storms, floods and droughts, as climate change makes weather more extreme.

“I’m not using the word existential, but this is a challenging market for insurers,” says Steve Bernardez, partners at Avanta Ventures, the investment arm of CSAA insurance, in what may be something of an understatement.

However, Bernardez and others in the insurance industry are investing in a new crop of insurtech startups with solutions that could allow them to better calculate and mitigate climate risks.

Bernardez joined Peter Ortez, senior associate at Munich Re Ventures, Kevin Stein, CEO and cofounder of Delos Insurance Solutions, and Matt Stein, cofounder and CEO of Salient Predictions, on our webinar on insurtech and climate change, to tell us about how these emerging companies are changing the industry.

Here’s what we learned:

1. Insurance companies are investing in both mitigating risk and calculating it better. The risk calculation part is more crucial in the short term.

Avanta Ventures’ parent company, CSAA, does a lot on the risk mitigation side, from partnering with private wildfire fighting units that will protect homeowners, to having homes sprayed with fire retardant — sometimes automatically.

But, for Avanta Ventures, the focus is on better ways to predict risk, so that it can get its underwriting right. The company is an investor not only in Delos and its new models for calculating fire risk, but it has also backed Cape Analytics, which uses drones and computer vision to estimate the risk of properties from the air.

Another portfolio company, Kin, provides insurance for high-risk areas where insurance is hard to get — such as Florida in the aftermath of Hurricane Ian

“It’s those types of companies that both either can partner with us directly, or we can kind of learn from, in turn as a corporate venture arm and with a parent that is a carrier, on how to do things in kind of a new way,” Bernardez says.

2. Reinsurers focus more on risk mitigation.

As Ortez puts it, reinsurance is, on a basic level, insurance for insurers, and, being one step removed from the front line, tends to take a broader view on investing.

Munich Re Ventures invests in new risk calculation models and in ways to mitigate climate change.

“On the climate side we want to go out and invest in those companies and technologies that are taking fossil fuels out of the equation, to try to reduce and potentially reverse the impact of climate change,” Ortez says.

Munich Re Ventures has invested in companies such as Zanskar which is creating an AI “treasure map” for geothermal resources. Another portfolio company, Twelve, is capturing CO2 and turning it into industrial chemicals.

3. The biggest problem isn’t insurers losing money — it is people not being able to get insured at all.

Unpredictable losses definitely hurt insurers. Bernardez points out that in 2018, when the deadliest and most destructive wildfire season in history hit California, it created $12bn in losses — but insurance companies had only been paid $9bn in premiums by homeowners. It doesn’t take a genius to see that multiple years of such losses would be unsustainable.

Ultimately, however, it has hurt customers the most. Many insurance companies have since left the state and homeowners have been left with few and more expensive insurance — or none at all.

Many insurance companies’ reaction to wildfire risk has been simply to walk away from the problem, says Kevin Stein of Delos Insurance.

“When we started the company in 2017, everybody said wildfire was a problem coming up in the next 60 years. And we said no, we’re pretty sure it is a problem right now.”

After the 2018 fires hit California, he says, “everybody said wildfires were too big and the problem was unpredictable. But we can’t live in a world where insurance companies look at a certain type of climate risks and say, Hey, I don’t understand that or that’s not predictable, and therefore we can’t do it.”

Many of the emerging insurtech startups are about trying to make what was previously considered “unpredictable” manageable again.

4. In the era of climate change, historical data becomes obsolete. New insurtech companies are moving away from a reliance on that.

Delos, for example, has developed a custom model of wildfire risk, using satellite imagery to pull together an understanding of how dry the vegetation in an area is, the topography, wind patterns and precipitation levels.

“We’ve been able to figure out where wind driven fires can and cannot happen,” says Stein. “There are a lot of areas that have not had a wind-driven fire that have those conditions very frequently, they just haven’t had an ignition on a bad day.” Meanwhile, there are other areas that may superficially look like areas ripe for wind-driven wildfires, but which would never have the right climatological conditions.

“They actually cannot have a wind-driven fire and therefore are significantly more insurable,” he says. The company now programs with six different insurance companies in California.

5. New insurtech models will look at data that might not have been considered relevant before.

Salient Predictions is a good example of a company that is looking at completely new sources of data — namely measuring the salt content of sea water and using that to predict where and how much it will rain.

“If you’re looking at the surface salinity level of the ocean at a specific location, and that salinity is increasing from week to week, that tells you that there’s more evaporation at that location. That evaporation turns into moisture in the atmosphere, and that will precipitate down as rainfall somewhere. Spotting that an increase somewhere in salinity increased precipitation somewhere allows you to draw the spatial and temporal connections,” explains Stein. Add some machine learning to be able to process industrial quantities of these connections and you have the basis for an interesting new way to predict rainfall — even as far as a year in advance.

The system was proven to be accurate in 2017 when it won a rainfall forecasting competition organised by the US government. It was up against a number of academic groups and private weather companies and beat these by a factor of two.

Since then, Salient Predictions branched out to more than just rainfall. “Our goal as a company, is to be the global standard in the two to 52-week timescale of weather forecasts,” Stein says. It could have a profound impact on being able to protect ourselves against previously “unpredictable” weather.

“Just think about the Texas freeze. If insurers and energy operators had had two, three, maybe even four weeks, to prepare — even if the signal was just a 60 or 70% chance — they could have done something. They could have simply insulated their pipes, and eliminated hundreds of millions of dollars of damages and losses.”

6. It’s not just about getting more data — it’s about developing better prediction models

The old way of calculating risk was to take 60 years of loss history data and use that as a prediction for the loss history of the next year.

“That doesn’t work in a climate-affected era. I strongly believe that the future of insuring properties in climate-affected areas will include climate predictions as at least a small part, if not a large part, of those models,” says Delos’ Kevin Stein.

And while Delos’ models will take in a lot of data, the team are wary of overfitting the model — creating a model that corresponds too exactly to the training data and therefore becomes poor at working with any new data. There is an emphasis, instead, on having a team of scientists who can make predictions and keep modifying the model.

Matt Stein of Salient Predictions has the same approach.

“You need that sort of integration into the scientific community. If it’s just training up machine learning models you’re going to overfit models. You need that scientific intuition to carefully construct these models.”

7. The future of insurance will be about consultancy

With these ways of predicting weather catastrophes, Stein believes that the future of the insurance industry will involve offering consulting services to customers to help them cut their risk.

“If you can provide the right kinds of consulting and data services…that’s really helpful. Being a little controversial, insurance firms that aren’t doing that are likely to get intermediated by reinsurance firms, other smart primary insurance firms, consulting firms, startups. I think that’s a really important service to be providing,” he says.

Bernardez says Avanta and CSAA are already doing some of this. In areas that are at a medium risk of wildfire, for example, they give homeowners lists of ways they can fireproof their homes and will give them discounts if they do these.

“In doing that we are going to be more affordable than a lot of other groups out there. We’re looking at the real risk, which allows people to actually get a policy,” he says

8. The insurance sector should hold up reasonably well during the downturn

Valuations in the insurance sector have tumbled, much as they have in every sector. The post-IPO performances of some much-feted insurance companies like Lemonade and Root have been lacklustre.

But Kevin Stein remains bullish about startup prospects. “If you’re investing in an early-stage company, they’re not going to exit during this downturn, unless the downturn lasts eight years. So why are the valuations affected?“

Ortez points out the insurtech market shouldn’t be seen as a monolith. “When you peel back the layers, there are a ton of different business models that have different risk profiles. Whether you’re taking on the risk directly, whether you’re being a managing general agent, whether you’re an enabler, or providing tools for insurtech companies, or whether you are going after the big guys. Those all have different headwinds and tailwinds,” he says.

Bernardez also believes there is room for insurtech to grow. “Insurtech has been a little bit behind fintech in terms of solving the problems for their industry. So, I firmly believe there’s a lot of opportunity and upside for startups in this space,” he says.

Watch the full discussion here:

The next webinar in our The Next Wave series will be: Who has the harder job — VC or CVC? at 9am PT on Wednesday November 9th, 2022. Register here to secure your place.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).