Corporate investors are backing chip startups with solutions for the generative AI's memory wall, interconnect and edge problems.

At times, the development of generative AI has seemed unstoppable. Products like ChatGPT have become a fixture of everyday life while the world’s largest tech companies scramble to build ever larger data centres for more powerful models. Corporate venture capital funds have dived in too. Over the last few years they have invested billions in startups innovating on the chip technology that allows AI to function.

But AI, like any developing technology, has its stumbling blocks. Chips with vast computing power are running below capacity because of memory restrictions, inefficiencies in design mean burning through unthinkable amounts of energy, and the technology is held remotely in large data centres rather than directly accessible on our devices.

These are all problems a wave of corporate-backed startups are hoping to solve.

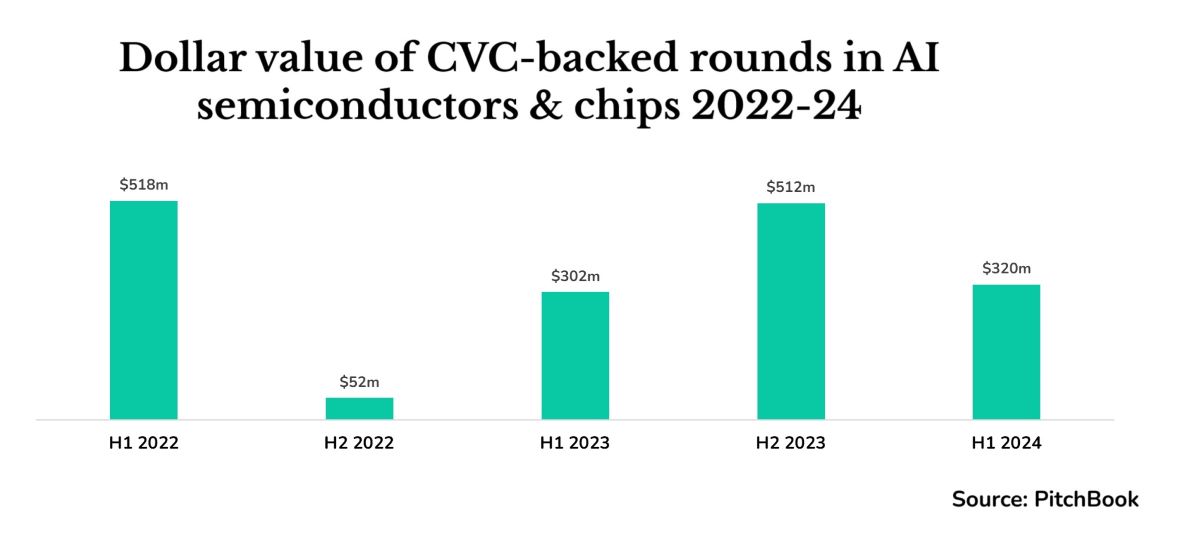

CVC-backed investment rounds in startups developing AI chips increased by 43% in 2023 from the previous year, according to data from PitchBook. Behind the headline figure is a range of different market niches being targeted, from new methods of information transfer on the wafer itself, to designs that could find their way into your smartphone, up to the architecture for the large chips that go into the most power-hungry data centres.

Today, the AI chip market is dominated by Nvidia, the US fabless semiconductor company which produces the graphics processing units (GPUs) which underpin AI model training.

Gradually, however, AI applications are going to move into widespread use by businesses and consumers, and the emphasis will shift from training AI models to using them to draw conclusions from live data, a process known as inference.

“There is growing importance to the memory wall and power consumption. This is an opportunity for new startups to disrupt.”

Dede Goldschmidt, Samsung Catalyst Fund.

Inference will be used in the running of everything from smartphone virtual assistants to self-driving cars. And as its use expands, it could open up opportunities for other chip companies specialising in specific device applications, or that make quicker, cheaper or more energy efficient chips.

“We think generative AI is really pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. While the focus has been on improving compute performance, there is growing importance to the memory wall and power consumption,” says Dede Goldschmidt, vice president, managing director and head of the Samsung Catalyst Fund. “Although you have incumbent players doing a wonderful job, this is an opportunity for new startups to disrupt.”

With the landscape shifting, here are some of the startups drawing attention from corporate venture capital units.

Nvidia’s challengers

Startups hoping to compete directly with Nvidia have a difficult path ahead. Not only does the chip design company dominate in the sale of hardware, accounting for a market share estimated to be between 70% and 95%, but it also supplies the software, Cuda, which users of the chips have become accustomed to.

“Nvidia continues to innovate,” said Amelia Armour, a partner at Amadeus Capital Partners, a VC company which closely monitors and invests in the sector. “It’s not as if you’re competing against a dominant player who hasn’t received investment in 20 years and the market is ripe for disruption.”

Despite this, big tech companies, semiconductor designers and businesses that plan to use the technology in their products are pouring investment into the sector.

Groq, a US chip design startup, is competing against Nvidia in the AI inference space, and claims its designs offer an advantage in speed performance. It raised $640m in its series D funding round in August, with investments from the CVC units of Cisco, a US technology supplier, and KDDI, a Japanese telecoms company, as well as Samsung Catalyst Fund.

Rivos is a US startup that is manufacturing a server-based AI chip with related software. The business news outlet Bloomberg reported that this chip would be positioned as a cheaper alternative to Nvidia’s GPUs. Intel Capital, the CVC arm of Intel, a US semiconductor company that competes with Nvidia, and Dell Technologies Capital, the CVC arm of US technology multinational Dell, both took part in the $250m series A-3 funding round for Rivos in April.

D-Matrix is a US chipmaker which is positioning itself for the generative AI inference market. It claims it will be able to achieve a lower total cost of ownership than GPUs with its digital-in memory compute chiplet-based inference platform, which will make inference by businesses affordable to deploy. Microsoft’s CVC, M12, took part in its $110m series B funding round in September 2023.

Microsoft’s support is significant. It is one of the tech companies that is investing heavily to build AI systems and is looking to reduce its reliance on Nvidia’s expensive GPUs.

But there is more to the AI semiconductor sector than the large chips designed for use in data centres.

Startups are also developing chips to be deployed on networked devices – what is known as the edge – such as smartphones, wearables, or autonomous vehicles. These can perform AI inference in the device itself, without communicating with a central server. Because of this, they are smaller and more specialised.

Other companies are working to tackle limitations within the chip design architecture, for example by improving data transfer speeds to reduce the downtime in computing caused by memory usage.

Samsung Catalyst Fund’s Goldschmidt says that the market is full of possibilities. “Each one of our portfolio companies has a unique and differentiated capability that allows them to be special for certain things. Yes, there can be overlap, but the market is huge.”

As AI starts to move over into applications we use in everyday life, corporate investors are surveying the landscape to find the potential winners in this technological shift.

The memory wall

A limitation in AI chip design comes from a problem known as the memory wall, and any innovative startups tackling it could gain a foothold in the market.

It was once thought that the key challenge in chip technology was increasing computing power.

“Today, we know that’s almost a useless metric,” says Christian Patze, an investment director at M Ventures, the CVC arm of the German materials company Merck, which supplies materials used in semiconductor manufacturing. The memory wall means that chips with a high amount of compute cannot make full use of it because the time spent transferring data from memory is time not spent doing computations.

“These models get so big that you run into memory issues where chips only reach 20% or 30% utilisation. They’re sitting there idle and that costs the data centre a lot of money. If you have faster interconnect, you could improve the utilisation of the GPUs.”

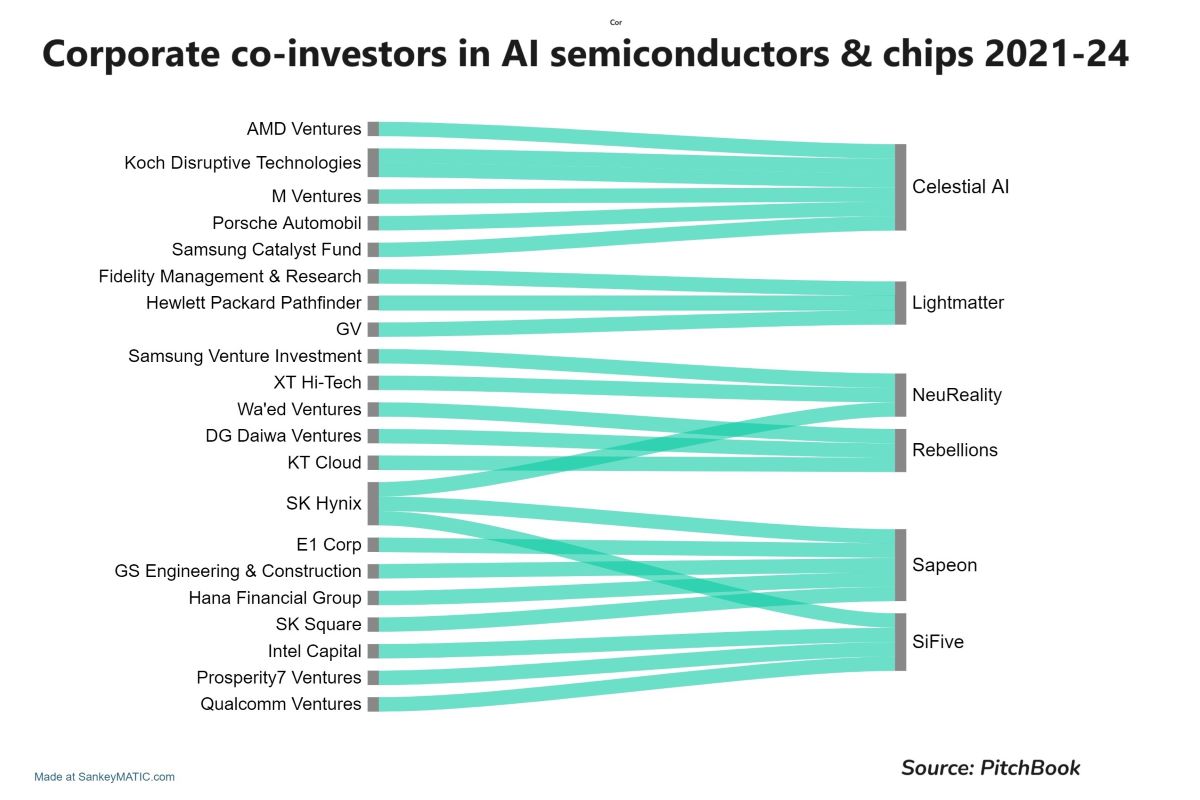

This is why M Ventures invested in Celestial AI, which is trying to speed up data transfer with optical interconnect technology, using photons for swifter communication on the chip between memory and compute.

“The hyperscalers do their own thing,” says Patze, referring to the large tech companies driving AI innovation such as Microsoft, Alphabet and Amazon, which are all trying to develop their own chips to reduce their dependency on Nvidia.

“This significantly tightens the market for selling datacenter AI accelerators but also opens an opportunity for companies with a solution to the interconnect problem to collaborate with the hyperscalers. That is what Celestial AI is doing.”

Tackling the memory wall is one area where corporates are hoping to see innovative startups flourish. In March, Celestial AI raised $175m in series C funding. Apart from M Ventures, other CVC funds involved in the deal include Samsung Catalyst Fund and AMD Ventures, the CVC arm of the US chip company AMD.

The new gold rush

Eliyan is a US startup that makes interconnect technology. Patrick Soheili, its cofounder, claims that its technology can reduce the proportion of power an AI server pod would ordinarily use on connectors from a 30-35% industry standard to 7-10%.

One level of connection Eliyan’s technology works on is between the components on the chip itself.

“The faster the link between the memory chiplet and the CPU chiplet, the faster that transaction is and the more memory transactions you can do,” Soheili says.

Because it makes technology that is generally applicable to chip design and manufacturing, Eliyan has received corporate backing from across the semiconductor industry. In March, its $60m series B funding round was co-led by Samsung Catalyst Fund with participation from the CVC arm of SK Hynix, a South Korean company that makes memory interfaces for chips. In August, it received an undisclosed amount from VentureTech Alliance, a VC fund partnered with TSMC, a Taiwanese semiconductor manufacturer that builds an estimated 90% of the world’s AI semiconductors, according to CNN.

This focus on interconnect and other AI-enabling technologies is a smart bet, believes Soheili. “In the Californian Gold Rush the miners didn’t make that much money overall,” he says. “But the guys that made axes, jeans and the little buckets that the gold miners used made a ton of money.”

Another AI chipmaker attracting corporate backing is Israeli startup NeuReality, which raised a $35m series A funding round led by Samsung Ventures with participation from SK Hynix. NeuReality is coming at the problem of utilisation from a different angle. When data is brought into an AI accelerator such as a GPU it is first processed by a CPU, which can host multiple GPUs at once. This funnelling and processing of data acts as a bottleneck, limiting GPU utilisation.

NeuReality seeks to update that CPU architecture. Through a device it calls the Network Addressable Processing Unit, it puts one chip in the front end for each GPU, which then uses its hardware for as much of the data processing as possible as soon as it is brought into the server.

As Moshe Tanach, NeuReality’s CEO, puts it, while the startups improving memory to compute connection are “building a stronger car engine” what NeuReality is doing is “adapting the car to be able to exploit that engine.”

AI on the edge

Not all the action is in data centres where the large AI models sit. Edge computing is another area where the AI chip market is still open.

Because this is AI inference performed at the device level, key considerations for edge AI chips are around efficiency and sophistication. They will have to power complex inference tasks without burning through battery life. But deployed correctly, they will allow everyday devices like smartphones to run AI-powered services.

Amelia Armour of Amadeus Capital Partners uses the example of an autonomous car.

“You need very fast processing of real-time data,” she says. “There’s no time for sending it back to a data centre, processing it there and then receiving a decision back. All that processing needs to take place within the autonomous vehicle on models that have already been trained.”

And unlike the market for data centre GPUs, which is dominated by Nvidia, the edge AI chip market is still open. Getting AI onto devices is still in the early phase. Samsung and Apple have both recently launched new phones with some AI features, but for now they are rudimentary, far below the capabilities of data centre LLMs.

“I don’t think it’s necessarily this generation of phone, but perhaps the generation after that when we’ll start seeing some real deployment [of edge-based LLM functionality],” says Paul Karazuba, marketing VP at Expedera, a Silicon Valley startup that makes semiconductor design intellectual property (IP) for chips to be used in edge AI inference.

“Every application processor, every microcontroller, every chip design of every performance level is going to have an AI engine if it doesn’t already. The market is potentially giant.”

Paul Karazuba, Expedera

In May, Expedera received $20m in series B funding led by Indie Semiconductor, a US fabless semiconductor company.

Karazuba says his company’s IP improves performance, power and latency in the neural processing units (NPUs) used for edge AI inference. As with Celestial AI and Eliyan, the value to customers is in speeding up processing, improving utilisation and therefore saving energy.

“There are so many potential use cases [of edge AI inference technology],” says Karazuba. “Every application processor, every microcontroller, every chip design of every performance level is going to have an AI engine if it doesn’t already. The market is potentially giant.”

Competitors in this space include Synopsys and Cadence, which are both large public US technology companies that license IP for system-on-chip architecture.

Scepticism about edge AI

Christian Patze from M Ventures is more sceptical about the growth potential of edge AI chips.

“With the rise of generative AI our investment focus has shifted away from edge AI to datacenter AI infrastructure and optical interconnect,” he says.

“The edge is very application dependent. It can be an attractive space if you have found your niche but from what we see in the market a lot of companies are struggling with that and eventually fail. It’s not enough anymore to offer yet another piece of semiconductor IP to do wake word recognition in Airpods.”

But M Ventures does have one edge AI chip design company in its portfolio: SynSense, a Chinese startup which is trying to make ultra-low energy chips which can perform live computations on sensory data with a relatively low power demand. Its chips are designed for applications including smart toys, home security devices and autonomous vehicles.

“AI is like a game of soccer with moving goalposts.”

Dede Goldschmidt, Samsung Catalyst Fund

Other CVC funds are more committed to backing edge AI.

Dell Technologies Capital took part in the $70m funding round for Sima.ai in April. Sima.ai makes chips designed for generative AI on the edge and is developing its second-generation chip with a target rollout in 2025.

In July, Axelera AI, a US edge AI chip designer raised $68m in series B funding, with participation from Samsung Catalyst Fund.

“While it’s important to optimise AI chip architecture to deliver high performance, this can come at the expense of flexibility and other general-purpose capabilities. It’s also important not to be completely limited to one application,” says Goldschmidt of what Samsung Catalyst Fund looks for in edge AI startups.

“It’s a huge market representing tremendous opportunity. But it is more fragmented by industries and customers. There’s a long tail of customers, but how do you reach them? The go-to-market motion is the challenge.”

Above all, says Goldschmidt, AI chip startups will have to be adaptable in order to make it

“AI is like a game of soccer with moving goalposts,” he says. “When you’re a semiconductor startup coming with disruptive new architecture, you need to be flexible enough to deal with the dynamics of AI models.”