Corporate investors are leaning into the ways they are different from VC investors and reaping the benefit in a tricky investment climate.

Venture capital may have seen a large decline in the past two years (down 35% in 2023 compared with 2022) but corporate venture funds have surprised everyone by remaining a constant in the market. In previous boom-and-bust cycles, such as the 2000 dotcom era, corporate investors rapidly retreated from the market. This time, it seems to be different.

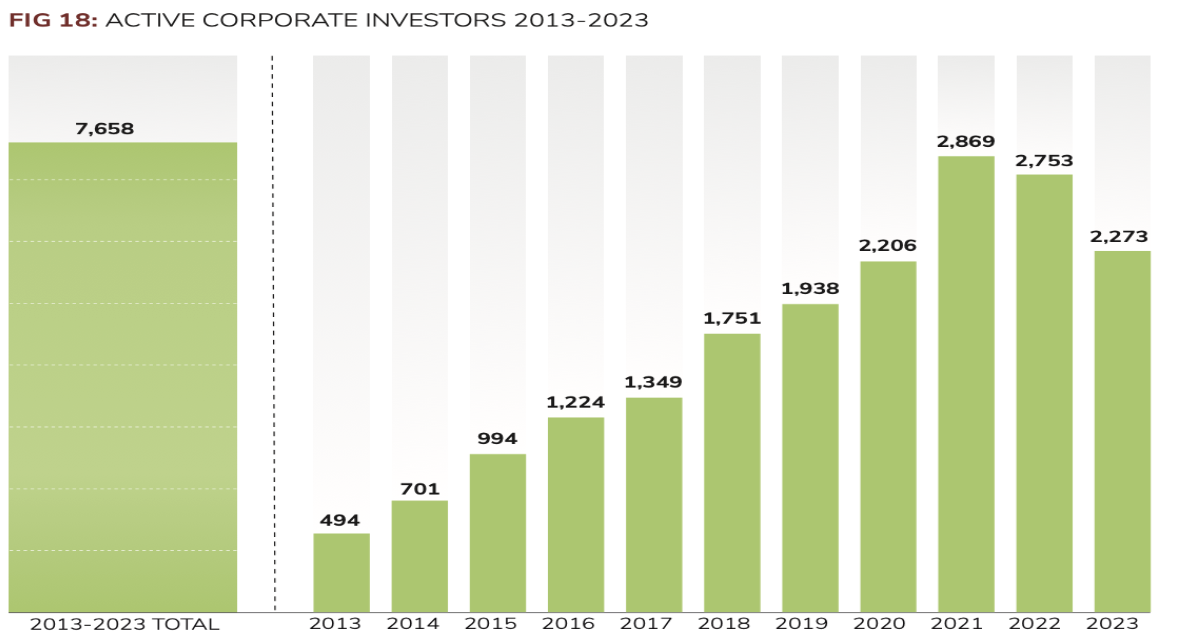

The number of active corporate venture units globally has declined from the peak of 2022, but there has not been a wholesale collapse.

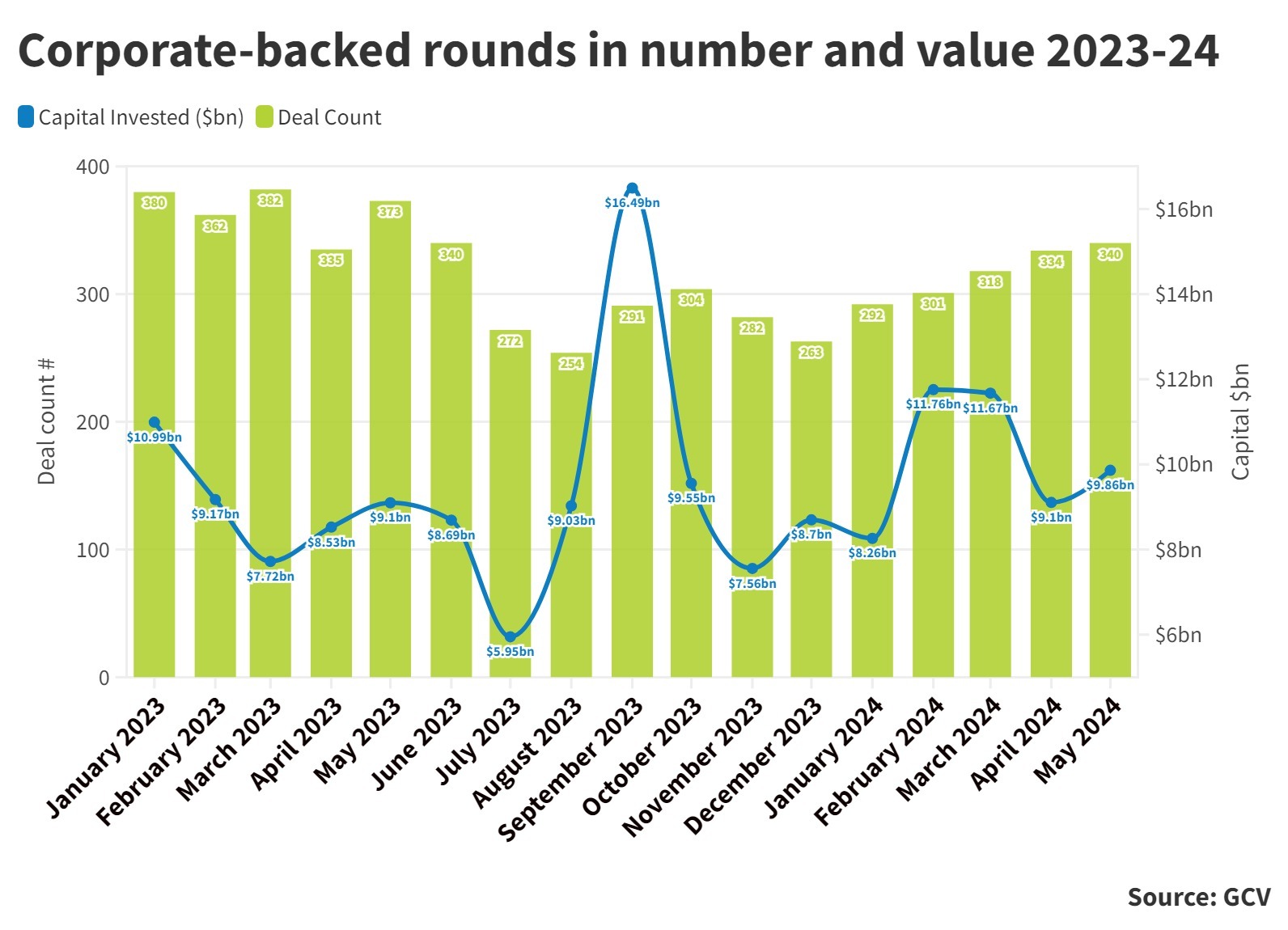

Though the number of corporate-backed funding rounds has dipped alongside the general decline in VC investment, since the start of the year we have seen the number of CVC-backed rounds creeping upward.

The difference has partly come because corporate investors are leaning into the difference between them and financial-only venture investors. Corporate investment arms can offer startups synergies with their parent corporations, can do more extensive due diligence on science-based propositions and are often willing to explore alternatives to standard equity investing.

All of this was sharply in focus this week as 340 attendees, a majority of them corporate investors, gathered for the annual Global Corporate Venturing Symposium in London. Here are five key themes that emerged from the conference.

1. Portfolio company partnerships are in sharp focus

One of the key themes of the Symposium was how corporate venturing units are increasingly focused on helping their portfolio companies work with business units at the parent company.

Ida Christine Brun from Maersk Growth told the audience how Maersk had shifted to a system where it could start working with a startup in three or four months, rather than the year it used to take to set up a collaboration. MassMutual Ventures aims for a commercial relationship between MassMutual and each of its startups within two years, and National Grid is streamlining the piloting process for startup technologies.

But you do need a push from the C-suite to make this happen, investors told us in more informal talks over drinks. Without business units being given specific perforrmace targets by the leadership to work with startups, it is hard to get the startups any meetings in the first place.

Many CVC investors were also candid in how much work was needed on their part in making the relationships with business units work. James Orchard of CEO of QBE Ventures at QBE Insurance, told the Symposium audience that interactions with startups and the company had been difficult because there had been too much emphasis on startup-style disruption. But when the team had learned to listen and fully understand the problems the business units wanted to solve, collaboration had improved.

“It is not just about finding a technology and shoving it down their throats,” he said.

Building and maintaining the relationship with the parent company is a non-trivial time commitment — we heard this again and again. Mitchell Yun, head of office at Hyundai Mobis Ventures, says he holds education sessions for the internal team at least 10 times a year and is always having to spend time “selling” the investment unit proposition to new managers who come in. “I have to pitch like a startup,” he said.

Watch the full session:

2. Injecting big-company ideas into startups

Another kind of help that corporates can give startups is advice on tools for how to operate as a larger company. Boris Hodakel, CEO of Feel, a digital health company backed by BTomorrow Ventures, noted the help on financial planning and modelling that he had received from the larger group. Although due diligence by corporate investors may sometimes be longer and more onerous than that done by their VC counterparts, a CVC investor may often leave a startup it backs more scalable and investment-ready.

That view was backed by Ilyas Khan, founding CEO of quantum computing company Cambridge Quantum, who said corporate due diligence is a “deeper and more relevant” process for deep tech startups than the VC equivalent, because the corporates have the experts and know more about the problem that needs to be solved.

Tokamak Energy, a UK-based fusion company, meanwhile, is bringing big-company tactics as it seeks to scale, with Rolls-Royce executive Warrick Matthews having recently taken the CEO role, and Warren East former CEO of Rolls-Royce and Arm, joining the board.

East is bringing ideas from the Arm playbook to Tokamak, with a vision for making it the “Arm of fusion”. This means embedding the technology into many partnerships and ecosystems, turning it into the technology that everyone in the sector builds on.

There is an added advantage to this, as the company can make some immediate revenue from selling its super-strength magnet technology to other sectors to generate immediate revenue while it works on developing the core fusion energy system. Nuclear fusion could be a viable proposition by the mid 2030s, but, in the meantime, the startup does not want to be dependent solely on large funding injections from investors.

See the full session:

3. Collaboration between CVCs and VCs

Corporate venturing appears to be increasingly tightly knit with the VC sector as more CVCs take limited partner (LP) positions in VC funds. This is not something that only new CVCs do to “learn the ropes” of investing. It is increasingly being used by experienced investors to broaden their reach.

Bogdan Gogu, head of UBS Next Investing, a CVC of the multinational bank UBS, said during a panel discussion that it is not practical for the investment unit to seek many small, early-stage companies through its CVC arm. His unit partners with VC funds to increase its exposure to the early-stage sector.

VC partnerships can also help CVC investors get access to deals in very competitive sectors such as artificial intelligence. For a corporate investor that wants to be part of a deal it can help if they are an LP in a well-known fund that is able to compete for the best deals, observed one corporate investor.

VC partners can also help manage relationships with startups when there is a lot of management churn at the parent company. Gabriela Ruggeri, managing partner at Kamay Ventures, a VC fund with corporate LPs, says one of its CVC partners has had five management changes in five years. “We are the constant,” said Ruggeri. “We take the burden of building a bridge between the startup and the corporate.”

There is, however, still some tension in the VC-CVC relationship, with corporates complaining that VCs can rush deal flow rather than taking time to understand the corporate’s needs. VCs, meanwhile, said that corporates often promise to provide strategic value for the startups they invest in but fail to deliver. One corporate investor said there was a need for more industry-specific VC funds that will take CVCs as limited partners.

Watch the full session:

4. Growing interest in corporate venture building

An increasing number of corporates are interested in running internal venture building operations alongside their investment activities as another way to tap into innovation.

Gurdeep Singh Kohli, partner on the SC Ventures venture building team, told a breakout session that Standard Chartered bank had seen this as a way to explore opportunities beyond its immediate core focus, and also to bring a more innovative mindset to the bank. Just investing in external startups would not have been enough to achieve this.

Venture building efforts have had mixed results, but Singh Kohli and Vuyo Mpako, who heads a similar operation at Old Mutual’s Next176 venture unit, offered some advice:

- Hire people from the outside to run the new venture, ideally a failed founder who has previous experience of working in a big corporation.

- Make sure the CTO is external.

- Incentivise the team with VC-style equity.

- Get the internal startup fundraising from the start so that it gets into the right mentality and never gets used to depending on corporate support.

- Have a wide funnel for new projects but be disciplined about culling the ones that don’t work. Have a majority of external people on the investment committee.

5. Investors need to devote more resources to analysing political risk

Geopolitical tensions are becoming a serious obstacle to funding. A roundtable held under Chatham House rules at the GCV Symposium acknowledged several deals that had become derailed because of connections to China, Russia or Iran.

Chinese startups that have already taken government money can be uneasy raising money from Western investors, as they may face uncomfortable questions from their government. There are some creative ways to get around this, with some Chinese startups setting up subsidiaries in Singapore to access Western private capital (is this why we have seen CVC deal activity growing so strongly in Singapore this year?)

Sometimes deals fail completely because of a geopolitical connection. A funding roud for one small gaming company recently failed because investors realised it had some negligible revenue from a few users from Iran (a country subject to sanctions). Another fund was being raised with a substantial Russian corporate commitment as the anchor, just before the war in Ukraine broke. The fund ultimately did not materialise.

There is concern that such tension will only increase with the rise of populist right-wing governments in recent times.

Investors are also withdrawing from investments involving military “dual use” technologies. Participants cited an example of a large fund of funds that had to withdraw commitments from several VC funds in this kind of technology, as its mandate explicitly forbids investing in military tech.

Another investor had to help a portfolio company developing such “dual use” technology with an emergency fundraising and save it, as many investors from the rest of the syndicate withdrew completely from it.

Despite these new challenges — many of which are heavily loaded with reputational risk, corporate investors admitted that they do not have a person specifically analysing political, compliance and reputation risk on the team. The task falls onto their legal counsels or comms departments.

All the videos from the GCV Symposium 2024 are available on the GCV YouTube channel.