Quantum computing, alternative packaging and recycling technology are a few of the deeptech sectors that are emerging in Finland's startup scene.

Finland’s technology scene used to be best known for mobile phone maker Nokia, and then for gaming companies like Angry Birds maker Rovio and Clash of Clans creator Supercell.

But its next iteration is likely to be deeptech, as a strong academic base and a batch of new hard tech-focused funds push early- stage venture activity toward edge technologies.

The country has a relatively low level of startup funding activity: figures from the Finnish Venture Capital Association record under €900m in funding for Finnish startups from seed to growth stage in 2021, in comparison to over €7bn raised by their Swedish counterparts. But a higher percentage of its early-stage companies are leaning into harder technology areas.

“When it comes to deep tech, Sweden boasts a larger number of startups while Finland stands out with approximately 30- 40% of its startup landscape dedicated to the deeptech sector,” says Inka Mero, managing partner of hard tech-focused venture capital firm Voima Ventures.

“This is the result of a long-term startup or business background but also scientific and academic backgrounds in AI, nano-electronics, advanced materials, biotech solutions, and optics and photonics. If you start looking at these core technology domains, you’re looking at the core building blocks for future businesses such as quantum computing or next-generation generative AI, or recycled materials which are needed in electronics.”

Finland punches above its weight in several technology areas. Its roots are in software, starting with Assembly, a gaming and demo event that goes back to the 90s and which acted as a meeting place and proving ground for the country’s coders.

This activity led to the birth of a vibrant gaming ecosystem that brought forth a clutch of highly valued startups like Rovio and Supercell. The modern tech scene was also fuelled by the rise and fall of mobile handset producer Nokia.

“The growth and success of Nokia meant that we had a huge pool of engineers within the communications stack but also with consumer-focused hardware design capabilities,” says Juha Lehtola, director of venture capital for state-owned venture firm Tesi.

“And then when Nokia started laying off people in 2010 or so, a lot of that talent has been redirected elsewhere.”

Initially they went to consumer-facing sectors like mobile devices, digital health and mobile payment, but in recent years a clutch of specialist venture firms has sprung up to fund harder tech areas, such as Innovestor (life sciences), Vendep Capital (software-as-a-service) and Voima, which just closed its €90m third fund. This in turn is supporting developers of edge products.

Biomaterials and quantum computing head Finland’s specialist tech areas

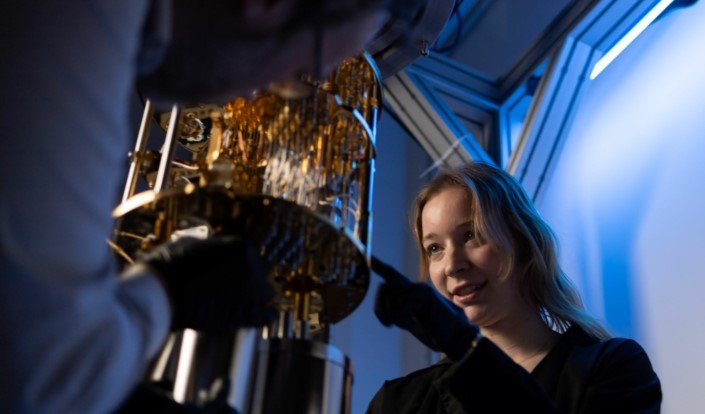

Quantum computing is still an emerging technology, but it is increasingly standing out as a key area for Finland, which established its first cold laboratory in the mid-1960s, and which is one of the only European countries to be collaborating with the US-based Quantum Economic Development Consortium.

Bluefors, which provides cryogenic cooling technology for quantum systems, spun out of Aalto University’s low temperature laboratory in 2008, paving the way for building supercooled quantum labs in the country. The largest quantum computing company in Finland is Tencent-backed unicorn IQM, and its ecosystem is even causing other quantum-based businesses, such as Oxford University spinout QuantrolOx, which develops machine learning software to manage qubits, to relocate.

“You could, of course, associate some of this development to these early flagship companies that raised a lot of funding and created a positive momentum,” Lehtola says. “That’s the fluffier thing, but in concrete terms, they also recruit and train a lot of talent on quantum technologies, and that may then spark new companies to be founded as well.

“At least that’s the historical timeline – I didn’t see anything before 2019 in terms of company activity in the quantum space in Finland. It’s really quite recent, and it’s continuously becoming bigger.”

An area where Finland’s traditional strengths are influencing its startup scene is forestry, unsurprising for a country where forests cover more than 70% of its land mass.

While the brunt of that business involves generating wood, paper and pulp, there are plenty of side streams that can feed into areas such as alternative packaging materials or recycling technology. Sulapac and Fiberwood are among the startups that have raised corporate funding for bio-based plastic alternatives in recent months.

“There are a lot of these companies, and the reason for that is you have a concentration of talent in the Nordics that knows how to regenerate valuable products from bio side streams,” Mero says. “And then if you look at the legislative environment in Europe, we’re now moving to a place where you have to invest a lot to circle our economy, to replace plastics and any fossil-based materials, any chemical industrial products.”

Will a strong education system overcome a funding gas and looming skills gap?

Although Finland’s edge technology startups are thriving at seed and series A stage, particularly with more specialist investors entering the arena, there is a question about whether they can make the next step in scaling. Funding often dried up from series C onwards.

“Your first €10m round, that’s the toughest one,” says Mero. “When you need to build your first satellite and get that to the sky, for instance, it gets narrow. That’s also why the Scandinavian and Baltic startups – and the Finnish ones of course – need to raise from global markets from the start.”

And Finland has not traditionally been a strong market for global investors, despite its technology prowess. That, however, could be changing, according to Panu Maulaheimo, venture advisor Helsinki Partners, a city-owned company providing investor services.

“Foreign venture capital flowing into Finland has more than doubled in two years,” Maulaheimo says. “I would say that it’s not a very well-kept secret anymore, so it’s definitely now something that is on the radar for some people at least.”

International corporates are investing in Finland – Samsung Next, Sumitomo’s Presidio Ventures and E.ON’s Future Energy Ventures are among the foreign CVC units to have backed Finnish startups of late – but the move to ‘harder’ tech is also being supported by local groups in infrastructure-heavy areas that are increasingly exploring early-stage investment.

The list includes forestry companies Stora Enso and Huhtamaki, which has set up a CVC arm under Tuikku Alaviitala, as well as oil supplier Neste and energy providers Fortum and Helen, which can not only invest but help as an early customer.

“There are several interesting large companies in the energy, chemicals – let’s say the harder tech space in general – that can partner with the startups and provide early venture client opportunities,” says Antti Ritala, who heads venturing and acquisitions for Neste. “So, companies like Neste or Fortum with ambitious climate targets are collaborating with startups. I think they play a role.”

Finland’s move towards more deep tech startups is supported by a strong academic grounding, boasting some 35 universities across a population of less than 6 million, while state-owned research institute VTT has in recent years spun out startups such as sustainable textile developer Spinnova and Solar Foods, which is working on technology that promises to create nutritional protein out of air.

The system has paid off so far, boosted by substantial government investment in education and free tuition fees for students from the European Union, though there are concerns it may not do so as much long term.

“For several decades, Finland consistently achieved top rankings in PISA assessments, particularly in mathematics and biosciences,” Mero says. “However, over the past five years, there has been a slight decline in these rankings, raising considerable concerns within the country about the current trajectory.”

Another issue the country may struggle with in future is that declining birth rates mean it is effectively losing thousands of people from the workforce each year, and it may have to begin importing qualified workers. There are warning signs emerging already.

“I think every Nordic country is fighting for global talent,” Mero adds. “We have the most challenging demographics in the whole of Europe here. We would roughly need something like 150,000 to 200,000 talent immigrants to the country by 2035. That’s a lot of people.

“We like to talk a lot about the Scandinavian and the Finnish miracle in terms of our startups, and I totally agree with that. I think we have massive opportunities. But if we don’t solve this one, big pressing problem, which is talent immigration, we’re not going to be the country where the money flows and the investments will happen, because in today’s global economy, if you think about where corporations establish their operations or where the money flows in terms of the startups, it’s where the talent is.”