University of Warwick spinout has developed additive technology that improves plastic production cost, performance and recyclability.

Plastics have been an undisputed game-changer in the materials industry but at a significant cost. Plastic production’s well-known detrimental environmental and health impacts have generated an industry-wide search for safer and alternative forms of plastic manufacturing.

Environment International researchers found plastic in the blood of 17 of 22 human participants in 2022, and an estimated 15-51 trillion pieces of plastics in the world’s oceans wreak havoc on ecosystems. Corporations have turned to startups to find non-toxic and biodegradable plastic packaging breakthroughs.

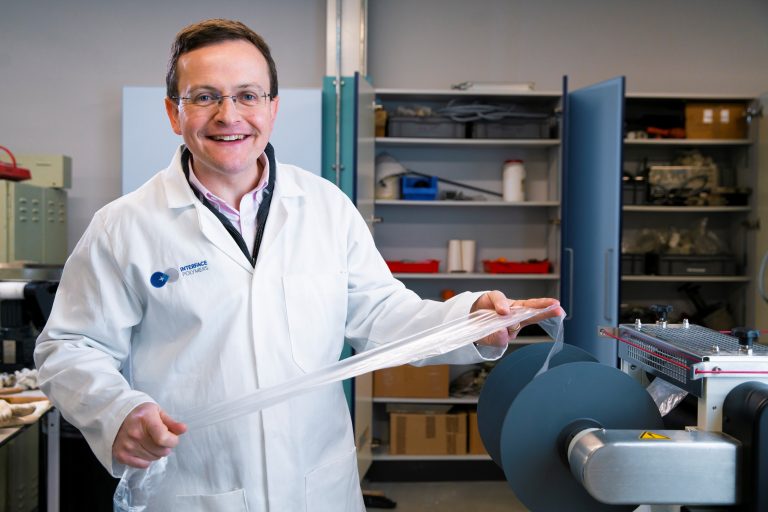

Interface Polymers (IPL), a UK-based startup, has manufactured a new additive dubbed polarfin, which has the potential to revolutionise the chemicals industry. Polarfin is intended to modify the surface properties of commodity plastics such as polyethylene and polypropene, creating a range of sustainable, customisable co-polymer materials that can be incorporated into existing manufacturing processes.

The technology is based on di-block co-polymers, which allow plastics to join onto other plastics materials, bridging two polymer molecules together. The startup’s technology ensures that processes can occur without changes to equipment whilst improving performance and cost savings.

Ross Baglin, chief executive of Interface Polymers, says that compatible isolation, which allows Interface Polymers to turn mixed streams of plastic into high value reusable plastics, will have a positive impact on the food industry.

“Melting of films is highly effective at keeping food fresh by keeping moisture and oxygen away from the food; but, when the film is unwrapped, the layered plastics can no longer be melted together and are therefore usually sent to landfill, incineration, or low value uses,” he says.

“Our technology can return a smooth high-quality film back to its original purpose, saving significant quantities of CO2 and general plastic waste, which all too often litters the environment.”

The company’s ability to reach industrial scale is what makes it stand out against its competitors, he says.

“Whilst researchers have long recognised that di-block co-polymers are an optimal solution for bonding and emulsifying mixed plastics, nobody has previously been able to develop a process at a modest cost, using commonly available materials, and with benign processing conditions.”

The multiple opportunities presented by surface functionality and compatibility for polymer additives was what drew Baglin to develop Interface Polymers.

Co-polymers can also tackle issues around surface functionality, as many common plastics generate low surface energy, meaning paints and glues do not take easily to these products, and the treatments available generate energy and a high defect rate.

Baglin believes that Interface Polymers addresses the industry’s long issue of surface functionality. “IPL’s Polarfin technology is able to change the surface energy of plastic substrates and make them permanently ready for glue, paint or ink adhesion. This will enable the adoption of polymers in place of higher energy intensity or heavier weight materials.”

Interface Polymers was founded in 2016 by Chris Kay, director and chief scientific officer, and Peter Scott, director. The management team consists of seven individuals who are well-established leaders in the polymer and technology startup industry.

Baglin, in particular, has more than 30 years experience in the oils and chemicals sector, serving eight as an executive vice president at Shell and ExxonMobil’s joint chemicals manufacturing subsidiary, Infineum International Limited. He also has held human resources positions at Shell from 2006 to 2010.

A difficult start to funding

The advanced materials sector is tough to break into. Many startups in the industrial sector have struggled to find their footing and have received little to no investment.

Examples of underfunded advanced materials startups include Nanoseen, a Poland-based developer of copper nanotubes and carbon nanotubes, which has raised only $450,000 since its launch in 2021. British startup RecyGen, which repurposes waste materials into raw materials through waste segregation, was founded in 2020 but has received no funding to date.

Baglin has also felt the effects of the difficult funding climate and says that investors who are not specialised in the chemicals and industrial sectors may find these startups less attractive.

“This sector is characterised by high barriers to entry especially in regulatory and knowledge and long lead times to revenue. Value can also be difficult to assess without significant strategic background and understanding of the relevant fields,” he says.

“We found it difficult in our early days to find financial investors. But we found a way once strategic industry investors were on board.”

Despite the industry hurdles, Interface Polymers has raised close to $10m, having recently secured $8m in a series A round led by GC Ventures, the corporate venture arm of the chemicals manufacturer GC.

Angel networks, such as London-based firm 24 Haymarket, also provided investment in 2018, which Baglin says was an integral relationship for Interface Polymers.

The funding will be used towards the construction of a 10T per anime pilot plant in Hyderabad and increase the company headcount from 12 to 17 in the R&D and sales departments, says Baglin.

The value of corporate investment

Aside from GC Ventures, Interface Polymers has received support from other established corporations such as Evonik’s corporate venture subsidiary, Evonik Venture Partners.

“The corporations mainly came to us because one of our board members had worked closely with our corporate investors,” says Baglin, “Other undisclosed corporate investors heard about our technology through the grapevine and showed interest, initially, as a customer, which then evolved into an interest in investment.”

Corporate investment has been vital in Interface Polymers’ efforts to scale up and further develop its technology.

“Our corporate financing has been used to develop and prove our technology and also create a small scale demonstration plant to show the success and benefits of our products,” says Baglin.

Baglin says that startups have to think smart when working with corporate backers. Large conglomerates have the potential to overshadow the potential success of startups, he says.

“Our challenge in working with big corporate backers is to leverage their industry contacts and market interest in order to help commercialise our products, without offering excessive exclusivity, which would drain much of the market opportunity away from IPL,” says Baglin.

Interface Polymers is a spinout from Warwick University, in the UK, and received financing from the institution back in 2016.

“The university was important in the early days, though less now. However, the initial discovery of Interface Polymers was due to a PhD course conducted at Warwick University, which later sold its shares of Interface Polymers in 2017 after giving us some seed capital and infrastructural support,” he says.