Space is a $1tn plus opportunity, even for companies outside the aerospace sector, and partnering early with new spacetech startups can give companies a head start. But consider these 5 things before you plunge in.

“Over the next 30 to 40 years, every industry will start operating in space. And in 100 years the economy of space will be bigger than the economy on Earth,” Daniel Faber, founder and CEO of space refuelling startup Orbit Fab, told the audience of GCV’s recent webinar on spacetech.

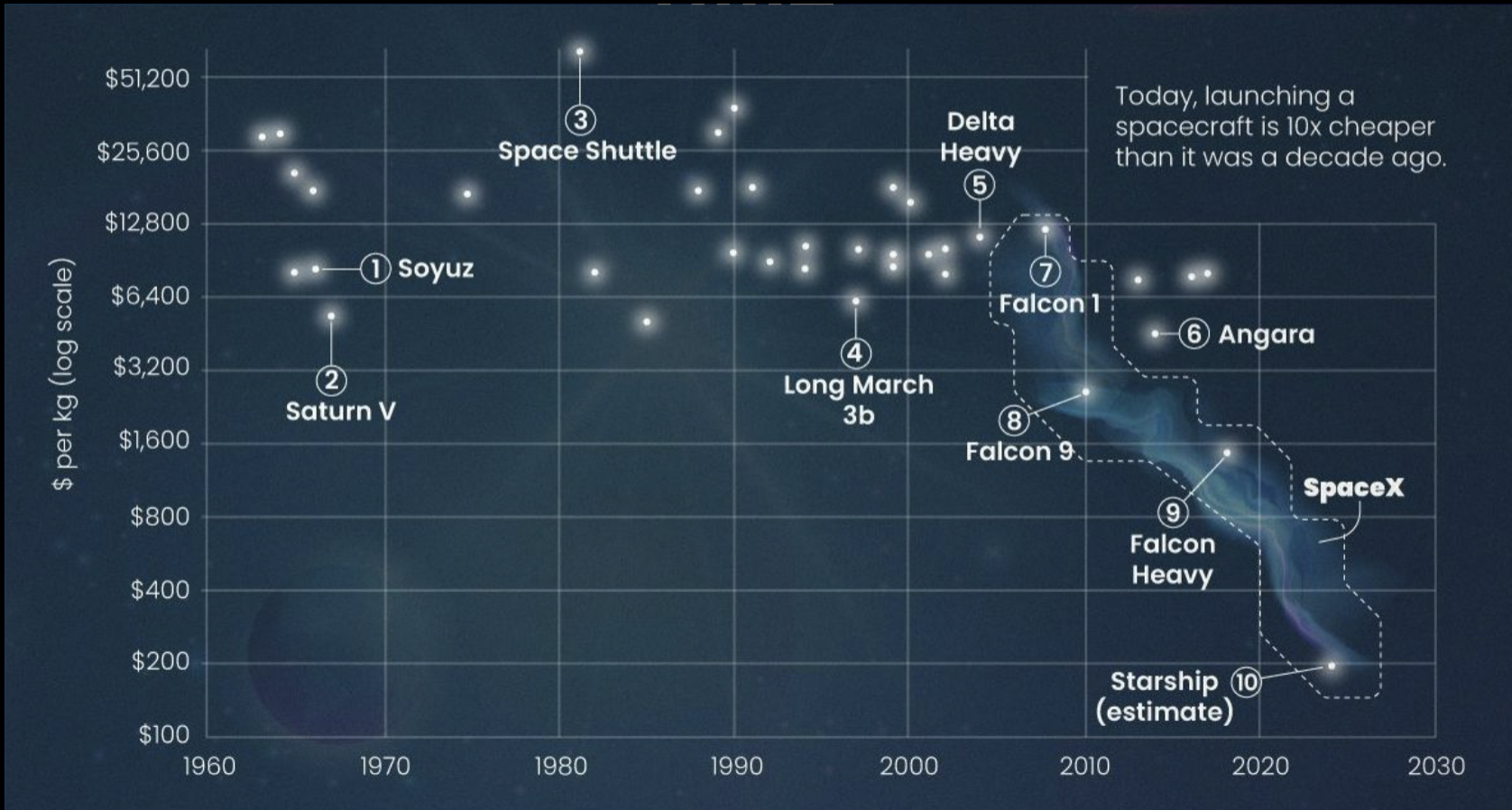

It has not escaped anyone’s notice that space has recently opened up in ways that seemed unimaginable 10 years ago. Not only has Elon Musk’s SpaceX demonstrated that private companies can handle rocket launches — and make them commercially viable — but overall, the cost of launching objects into space has fallen by a factor of 10 in the past decade.

The cost of spaceflight over time

Capitalist

This has meant a slew of new startups entering the “new space” business, including the two on our panel — Orbit Fab, a Colorado-based company that plans to build “gas stations in space” for in-space refuelling of satellites, and Helios, an Israeli company developing technologies to extract metals and oxygen from the martian and lunar soil.

Jonathan Geifman, founder and CEO of Helios, said it would have been impossible to start the business a decade ago, because the company would not have even been able to take the first steps in sending equipment to the moon to prove the technology could work.

“Ten years ago, the thinking of sending a small box to the moon was unconceivable. Today we have a price tag, it’s $1m per kilogram, it’s definitely doable,” he said.

The space industry could be worth $1tn by 2040, according to an analysis by Citigroup earlier this year.

How new space is changing old companies

But “new space” is not just for startups — it is also making space relevant for companies far outside the aerospace sector. Look at the roster of companies that have invested in Orbit Fab and Helios, and alongside expected names like Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman, you’ll find reinsurance company Munich Re, Japanese conglomerate Marubeni and mining company Anglo American.

Munich Re might not be as much of a surprise as you’d think — it was already the biggest insurer of both space launches and in-orbit space assets, Timur Davis, principal at Munich Re Ventures, told the webinar audience. But 10 years ago that meant writing one $100m insurance policy for a satellite or a rocket launch every year.

“Now you are writing one policy a week. Everyone is launching things and the prices are very different,” he said. “Before you were launching a $500 million satellite with a 20 year lifetime. From the insurance perspective that is a single huge policy that’s worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Now it could be several $100,000 for a small nanosatellite, with a lifetime of maybe three years.”

Investing in spacetech startups like Orbit Fab is helping Munich Re understand how space insurance is changing — and what new opportunities might be coming up.

“Through our venture investing we’re trying to bring in really new, innovative, exciting concepts and help our colleagues on the insurance and underwriting side think about what new space looks like from an insurance perspective, and maybe what are entirely new business models that can evolve out of this,” Davis said.

Orbit Fab’s Faber said that he is increasingly having conversations with companies that have previously had no connection with space.

“We’ve had many conversations with industrial gas supply companies and oil and gas companies,” he said.

Roee Furman, managing director of Doral Energy-Tech Ventures, meanwhile, is interested in spacetech companies like Helios, because their technologies also have immediate uses on Earth. Helios’s technology for extracting oxygen from moondust can also used to help the steel industry lower its carbon footprint.

“If it was just a space story it would have been more complex to sell this to our investment committee,” said Furman.

Here’s what companies should consider if they look at investing in space:

1. Space is the ultimate “moonshot” for your portfolio

Part of the reason Munich Re has gone big on space, says Davis, is because it has the potential to bring outsized returns.

“We realised there is a need to have investments with a long horizon, with huge payouts,” said Davis. Munich Re Ventures launched a deeptech practice a few years ago looking at a wide range of technologies, but space became a key theme and is now part of a transport strategy that goes beyond just space.

“As we’ve evolved, we’ve realised that there’s a need to have stuff in the portfolio that has a long time horizon, but a huge payout — high risk, high reward. We came to realise very early on that the potential of what is possible in space is tremendous, in large part thanks to the reduction in launch cost but other technological advancements as well. We’re opening up an industry that used to be the domain of governments and kind of very large defense companies, and nobody else.

2. Government-related industries are good bets in a downturn

Despite the arrival of private companies like SpaceX, the space business still involves a lot of government spending, and tapping into that is a good thing as other funding becomes more constrained in the downturn. VCs are already picking up on this, said Geifman.

“We’ve seen VCs now having more of an appetite for businesses that have a component of government business, whereas previously that was not so attractive. That may be a feature of the economic environment,” he said.

3. Bet on picks and shovels

The best bets in space, as in any new market, come from backing the “picks and shovels” companies, the ones making the tools that will enable other space businesses to operate.

For example, some 120 companies offer “tow-truck” services in space, small rockets that can help manoeuvre satellites into new orbits, or take them out of orbit when they are no longer functional. Faber estimates it is a $500m business just helping old satellites de-orbit. But all these tow-trucking companies are vulnerable to the same thing — running out of fuel.

“It’s like building a shiny new tow truck, going out, towing two cars and then throwing away the tow truck because you ran out of fuel. It does not make sense. By providing fuel in orbit, we are trying to help some of our customers that are these tow-truck companies realise this $500m market.”

Faber’s bet is that, whatever the space industry looks like 10 or 20 years’ time, it will have a pressing need for fuel.

4. Even non-space corporates can open doors for spacetech startups

Corporate investors — even ones outside the aerospace sector — can be very helpful in getting startups through the thicket of bureaucracy that surrounds a sector with international reach and a lot of national security sensitivities.

“Working together with big corporates that know how to operate within the realm of export controls and all the things that for a small startup seem very scary. This by itself is a huge benefit for us,” said Geifman.

Corporate partners can also teach startups a lot about their particular sectors, he said.

“Oil and gas, and industrial chemicals are almost parallel to us, we’re just taking those business models and applying them in space. And there are nuances, and we’re figuring out those nuances. That for us has been the real reason that we’ve been interested in getting CVCs on our cap table.”

5. Space is going to be a legal and regulatory wild west for some time.

“Even if there are laws, there is no one there to enforce them,” said Geifman. There has been a lot of work done by international committees and the UN to establish conventions for the moon. But not much is yet clear. If a company wants to mine the moon, who grants the permission?

Countries like the US, Japan, the United Arab Emirates and Luxembourg have laws that state that a company can sell any resource they have excavated, so if you are able to scoop up some moon regolith, you can, in theory sell it. But not all countries follow this principle.

“I expect what’ll happen is that people will just do things. And as long as nothing goes wrong, no one complains, and there’s no issues, that will become the standard practice,” says Faber.

These were just some of the insights from the webinar. You can watch the full session here:

This webinar is part of GCV’s monthly Next Wave webinar series in which we discuss both the art of CVC investing and emerging investment areas. The next webinar will be Wiring the Corporation – Creating new pathways for disruptive innovation, at 9am PT on Wednesday January 11th. Sign up here to secure your place.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).