As corporate venture capital units compete more with financial VC firms for talented investors, they are having to get creative on compensation packages.

When JetBlue Ventures was set up seven years ago as the corporate venture arm of the US airline, it took the unusual step of structuring itself as an independent limited liability company while remaining a subsidiary of the parent corporation.

The founders chose this structure specifically so that they could pay staff a form of VC-style compensation known as carried interest. Carry, as it is also called, is the percentage of a private fund’s investment profits that managers receive as compensation. It is the most common way to incentivise staff performance at private equity and financial venture capital funds.

For corporate investment arms, though, carry can be a tricky construct. CVC units have to be structured independently of their parent, often as a limited partnership, to offer carry. And even then, it can be a tough sell for the corporate parent because of the chance that a CVC employee will earn more compensation than the CEO of the company. This can look bad to the mothership’s management, board and shareholders.

To carry or not to carry

Nevertheless, more CVCs are offering carry, often in the form of a synthetic carried interest, to attract investment professionals from the banking and institutional venture capital sectors. And as more corporate investment arms take on external limited partners as part of their funds, the need to hire investment professionals who will drive financial performance has become greater.

Up to two-thirds of investment professionals are recruited from an external talent pool that includes VCs, other CVCs and private equity firms, according to GCV Keystone survey for 2022-2023. And, of the 30% of CVCs that are structured as independent legal entities, 65% have a synthetic form of carry.

“I have a lot of conversations with colleagues about carry because everyone wants it,” says Amy Burr, president at JetBlue Ventures. “It works for us because we do have more of a venture focus than a lot of CVCs. Our goals aren’t tied to the mothership at all. They are tied to goals we have around fund performance, investments, and a strategic initiative with our mothership.”

Global Corporate Venturing (GCV) knows of at least 40 CVCs that offer a form of carry as part of their compensation package.

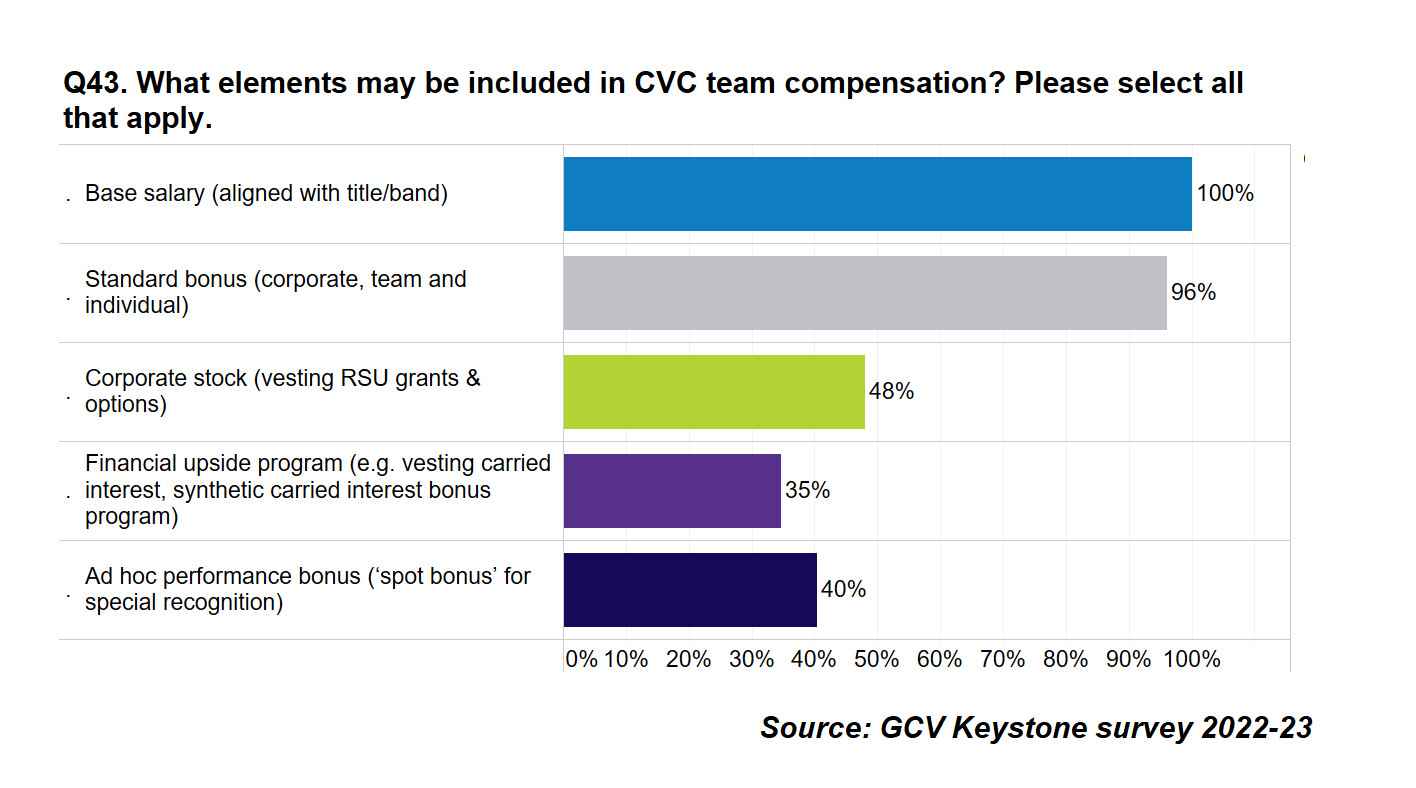

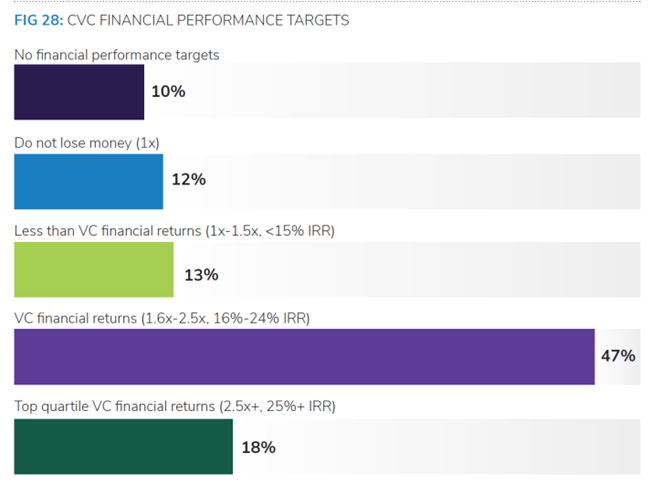

In a recent GCV Keystone survey, 35% of CVCs said they offer a form of carried interest. Two-thirds of CVCs now have at least VC-level performance measures, with 42% of these offering synthetic carry programmes.

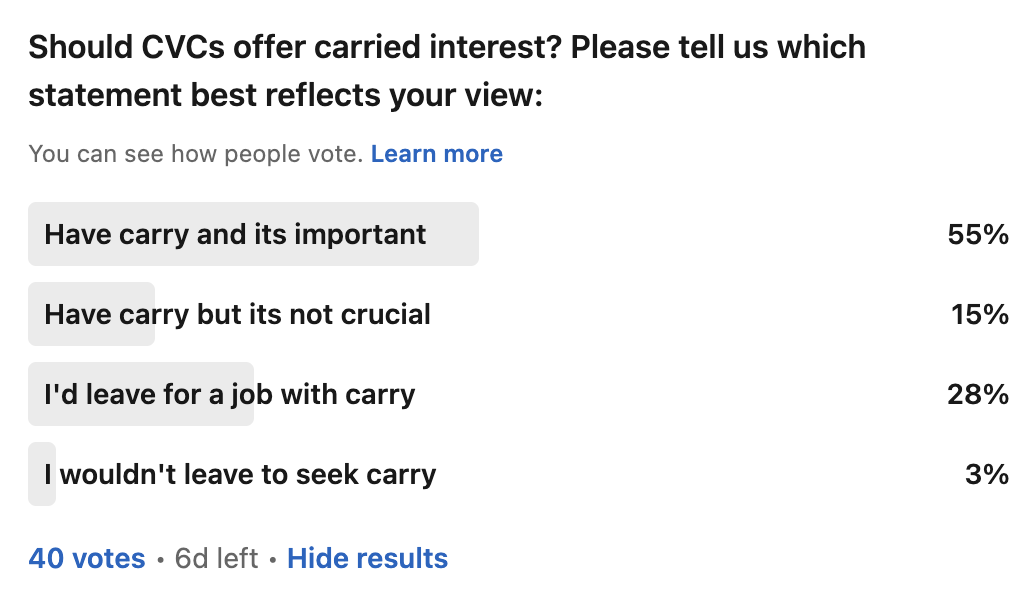

A poll carried out on LinkedIn by GCV in July found carried interest is highly valued by corporate venturing practitioners.

Most respondents to a separate CVC poll wish their CVC offered carried interest, although a lack of carry wouldn’t make them leave.

Offering carried interest to CVC staff is a no-brainer, says one head of a corporate venture capital unit who asked not to be named. “Carry is long-term in nature; it only becomes something when you monetise it. It is a retention programme, essentially,” he says.

In JetBlue’s case, its carried interest is triggered when an investment exits. But, before staff are paid out, the money generated from the exit has to pay back all its costs – the entire money invested in the company as well as the fund money of the first year it was invested in. Once that happens, 80% of the money goes to JetBlue and 20% goes to the venturing unit. All staff at the unit above a certain level are eligible to receive carry, including the business development team.

After seven years in business the unit just recently had its first carry-eligible exit that produced a staff pay-out, says Burr. “It can take a while to get there,” she says.

For those funds that are not set up as independent CVCs with a general partner/limited partner structure, synthetic carry can be offered to staff. This type of compensation mimics true carry but is usually paid out as a bonus that is treated as ordinary income and does not have the tax benefits of true carry.

Carry is not all that it is cracked up to be

Despite the hype around carried interest, it shouldn’t be seen as the be-all-and-end-all. “Offering carry at a CVC shouldn’t necessarily be the north star,” says Michael Yang, managing partner at Omers Ventures, the private equity investment arm of Canadian pension plan Omers. “Practitioners will tell you that compensation should be a combination of fixed and variable: fixed being salary and variable being any other component that is more performance oriented. That could be carry but it could be cash bonus, it could be equity,” he says.

Yang, who used to be managing director at Comcast Ventures, points out that senior members of a CVC can make enough in fixed and variable compensation that their overall paycheck will rival that of a VC professional. “Unless you are at a massive AUM venture fund where your fees are impressive, being a VC is a tough way to make a living unless you can consistently deliver the returns. There are many VCs who haven’t seen the personal wealth creation that they had hoped for because of the nature of the markets,” says Yang.

Carried interest often also has a long vesting period, meaning VC professionals will not receive full carry compensation unless they stay for a certain period of time. The vesting term for carried interest continues to grow and today is around 10 years, says Jody Thelander, founder and CEO of J. Thelander Consulting, a compensation consulting firm.

The long vesting period makes it even harder for CVCs to attract talented people from institutional VCs. “The good people are very much in demand. But, because of the length of time for the vesting of carried interest, those good people have no interest to leave a firm. The time to liquidity is taking even longer. They are even more tied to their venture firm,” says Thelander.

For many CVCs, the benefits of corporate ownership, including not having to deal with the pressures of raising money for a fund like at a VC – especially in today’s tough economic conditions – outweigh the higher compensation you can earn at institutional venture firms.

“You can do well financially in a corporate – you get salary, bonus, stock, equity. You don’t have to fundraise,” says Bill Taranto, president of MSD Global Health Innovation Fund. “When you go to a private fund, unless you are a general partner and own the fund, partners don’t earn that much money.”

Taranto is not a fan of offering carry at CVCs, mostly because of the issue of potentially earning more than the CEO of the parent company in the case of a big exit. In most cases, you can have a professionally run CVC and not worry about carry, he says.

For others, carry is not much of an issue when it comes to attracting talent. It is the lower base compensation that bothers people who come from a financial VC background. The CVC unit head who asked not to named says people who have a traditional VC compensation mindset don’t get past the first round of interviews at his unit because it can’t match those expectations.

Carry may not be the only competitive answer, particularly in a challenging VC environment.

Liz Arrington, managing director, GCV Institute

Offering stock in the parent is one good way of making up the financial gap in compensation. In Thelander Consulting’s most recent year-end CVC compensation survey, 63% of 129 CVC respondents said corporate stock is part of their compensation incentive package.

“Carry may not be the only competitive answer, particularly in a challenging VC environment,” says Liz Arrington, managing director of the GCV Institute. “Some industries like financial services and life sciences may be able to offer extremely competitive base salary, bonus and benefits packages, and fast-growth technology sector compensation has long included generous parent equity programmes,” she says.

At JetBlue Ventures, the unit’s choice to offer carry instead of stock in the parent company has proven to be a mixed bag when recruiting, says Burr. “It can be a negative for people who are more corporate focused when they realise that they are not going to get stock in the mothership,” she says.

For those that can’t offer a base compensation that competes with VC firms, company perks like being able to work remotely, opportunity to travel, company discounts and better work-life balance can also attract VC investment professionals.

But, with more convergence around expectations for CVC investment professionalism, “the adoption of programmes that recognise financial performance will continue to rise,” says Arrington.