SoftBank's $120m sale of Paytm stock at a loss came in the same week as valuation cuts for Swiggy, Ola and Zomato as India's once promising startup scene hits turbulence.

Telecommunications and internet group SoftBank’s sale of a 2% stake in India-based payment technology provider Paytm at a steep decline from its earlier price headed up a bad week for large Indian tech companies in an area that has been stalling.

SoftBank sold $120m of shares in Paytm’s publicly listed parent company, One97 Communications, at a valuation less than half what it was in late 2021. It would be easy to point to this as more evidence of SoftBank’s woes, particularly in light of the $32bn annual loss announced by its Vision Fund on Wednesday.

But it is likely more indicative of what’s going on in India. Paytm’s shares had already dropped in January when another large corporate investor, ecommerce group Alibaba, divested a 3% stake at a big discount to its trading price. And this was a week when several of the country’s most prominent tech companies experienced similar troubles.

Asset management firm Invesco cut the valuation of its investment in Indian food delivery service Swiggy by almost 50% on Monday to about $5.5bn. Shares of Swiggy rival Zomato subsequently fell 6% while another asset manager, Vanguard, revealed in its latest financial report on Wednesday that it had slashed the valuation of portfolio company Ola, a ride hailing platform valued at $7.3bn in 2021, by 35% in February.

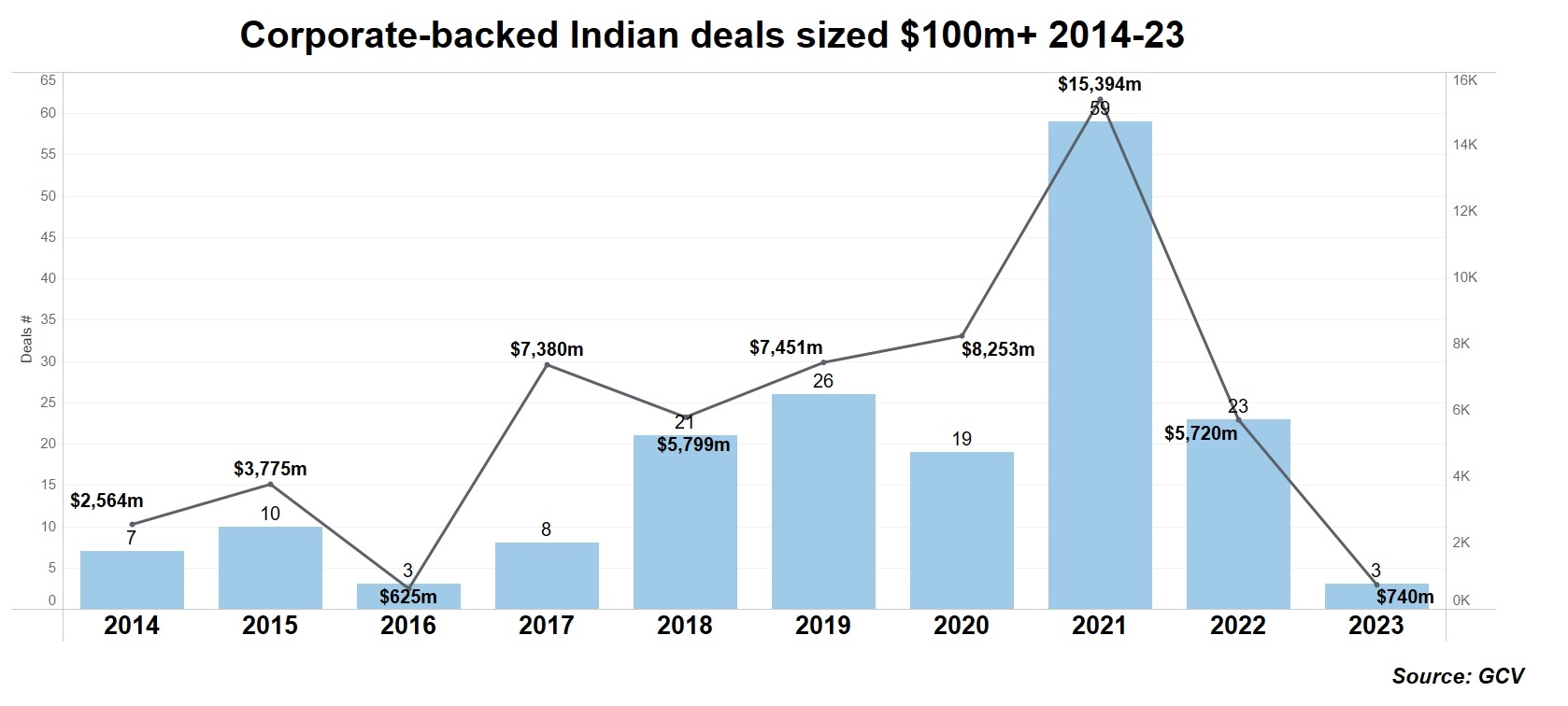

Growth-stage Indian companies have witnessed a big fall in corporate venture capital backing over the past year, as reflected in the chart below, which shows how CVC investors are slowing their investments in late-stage Indian startups. If these figures stay steady to the end of the year, they won’t get near 2014 or 2015, let alone the coronavirus boom period.

India’s startup space has long been touted as a potential goldmine, with Swiggy, Zomato, Paytm and Ola being joined by the likes of branded hotel chain Oyo, online education provider Byju’s, mobile money transfer service PhonePe, and online marketplaces Flipkart and Snapdeal among the fastest growing unicorns of the past decade.

In isolation, that makes sense. India’s population is expected to overtake China’s this year, giving it a potentially vast market. If you ignore the lockdown year of 2020, its GDP has been growing at an average of nearly 7% a year since 2018.

That is echoed in the revenues of some of the country’s largest firms. Tata said in February it expects revenues to increase by 20% this financial year while fellow conglomerate Reliance Industries and IT services firm Infosys recorded similar revenue growth in 2022.

India’s newer tech companies, the ones that have floated or raised huge VC money in the past decade, are finding the going trickier.

The country’s startup scene has always been heavily reliant on consumer offerings as opposed to hard tech. And while the figures above look promising on the surface, smartphone penetration in India is under 47%, markedly lower than in the other BRIC countries (Brazil, Indonesia and China) where it is above 68%.

India’s GDP per capita is also at the bottom of the group, and both factors provide a barrier when your product is app-based and aimed at middle-income users.

These issues affect growth. If you look at share price alone, China’s publicly traded tech companies appear to be doing worse than India’s, but they remain wildly profitable despite regulatory issues domestically and abroad. The likes of Paytm and Zomato, meanwhile, are still in the growth stage, yet to reach net profitability, let alone the kinds of mega profits achieved by their Chinese counterparts.

Then you get to territory. Corporates like Infosys or Tata are successful because they have managed to expand internationally, but the growth of newer Indian tech companies has been restricted because they remain chiefly domestic.

Without diversifying into new areas, there is no obvious market to grow into the way an Indonesian startup can expand elsewhere in Southeast Asia or a Brazilian company in Latin America. Bigger new markets tend to have already been nailed down by a local incumbent or a multinational giant.

The valuation decline is to some extent contextual – no one is pulling up trees in the tech space right now and many late-stage companies have cut their valuations, even if western tech companies with more diverse offerings like Amazon, Microsoft and Alphabet have all seen their stock rise at least 25% since the start of the year, as have more specialist consumer offerings with global reach like Uber and Airbnb.

It’s also important to stress that this looks like a trend rather than a sentence, and it’s by no means universal. PhonePe, for example, raised $200m from Walmart in March at a $12bn valuation, more than double that of 2021, on the back of an expansion into insurance and mutual funds.

But the situation also makes things difficult for the biggest corporate investors in Indian startups, with SoftBank at the top. The downgrades this week came eight months after the corporate cut its internal valuation of Oyo (of which it owns 45%) to about 27% of what it was in 2019, and six weeks after it reportedly slashed the size of the startup’s planned IPO by two thirds.

In short, the bleeding is unlikely to be over for corporates that invested at these companies’ peak, and many are stepping back.

Zomato halted its corporate venture activities last year while international corporates with local funds have notably been less active. Amazon’s Smbhav Venture Fund and Bertelsmann’s India Investment unit have disclosed one deal between them this year despite the latter’s $500m funding pledge last June.

TDK Ventures, on the other hand, launched an India hub in February. While it is yet to reveal an investment there since, the presence of a tech rather than consumer-focused CVC unit has to be a good sign. As for India’s late-stage, consumer-facing tech companies, they need to find a route to profit and to sustainable growth if they’re going to net decent returns for their CVC backers.

Lead photo courtesy of Shubham Rath via Unsplash