Influential university groups like TenU and the policy agenda of the new UK Labour government are leading to a rethink on the appropriate ownership that universities should take in spinouts.

After consulting entrepreneurs, spinout founders and investors, the University of Southampton’s technology transfer office recently lowered the equity it takes in IP-heavy spinout companies to 10%.

The decision, implemented in May 2024, changed a decade-long policy at the UK university of taking a third of the shares in companies that it helps to commercialise.

David Woolley, head of technology transfer and IP at the University of Southampton, says the decision was taken not just to appease investors, who tend to balk at university shares in spinouts that are more than 20%, but also to incentivise founders and increase the pipeline of spinouts from the university.

“When we really crunched the numbers, looking at the university’s annual returns and comparable organisations, what came out clearly is that Southampton does well for spinouts, but for its size and research base it does too few spinouts. Its run rate is low.

“We had a deliberate objective of increasing the number of spinouts. So, we said, what can we do to make it founder friendly and investor attractive,” says Woolley.

The move to lower equity comes amid a sea change among UK universities towards the ownership shares they have in the companies they seek to commercialise. Much of this has been driven by TenU, an influential group of 10 leading research universities mostly from the UK and the US, that last year released recommendations that equity in life sciences spinouts should be no higher than 25%. This year, it recommended universities take shares in software companies that do not exceed 10%.

The guidelines are part of efforts to attract more venture capital investment to UK spinouts, which often struggle to raise funding. The UK has world-renowned research universities such as Cambridge and Oxford and leads Europe in the number of university spinouts it creates, but it lags countries like the US on scaling spinouts beyond pre-seed funding rounds.

TenU’s recommendations have been bolstered by the UK’s new Labour government, which wants to increase spinout numbers as part of its focus on boosting economic growth. The party supports university equity shares at or below 10%. And, in a sign that it wants more transparency in the ownership that universities take in companies, it plans to publish annually a dashboard summarising the average equity each university has taken in spinouts over the past five years and the number of spinouts each has created.

Policymakers’ push for lower equity is having an impact. The average equity share for UK university spinouts has decreased to 18% from 25% in the past 10 years, with many of the top 10 UK universities doing deals of between 5% and 15% equity, according to a report by the Russell Group, an association of 24 UK universities.

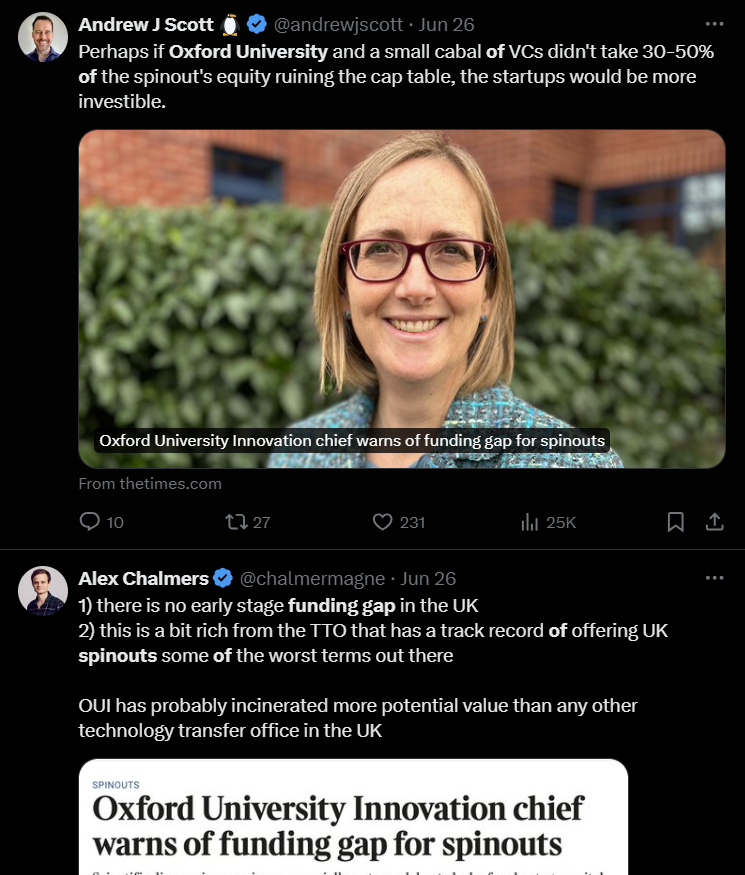

But despite the move to lower equity stakes, VCs continue to complain about what they see as restrictive investing terms. The University of Oxford’s tech transfer office was recently subject to criticism after CEO Mairi Gibbs was quoted by the Times warning of a funding gap for spinouts. VCs complained on social media platform X that the university’s commercialisation terms are to blame for the lack of funding.

A spokesman for the technology transfer office, Oxford University Innovation, says the Times article addresses the challenges associated with securing very early phase funding, which is essential for testing and validating new research concepts before they can be licensed or developed into companies. This proof-of-concept funding typically comes from government sources or early phase translational funds, rather than from venture capital investors. “It is important to note that the focus [of the article] is not on a lack of VC investment,” says the spokesman.

Some argue that equity stakes have no bearing on spinouts’ ability to attract VC investment. An oft-cited report by the Policy Evidence Unit for University Commercialisation and Innovation, part of the University of Cambridge, finds only a weak relationship between university founding equity and the initial investment success of spinouts.

Certain investors share this view. Moray Wright, CEO of UK Parkwalk Advisors, one of the largest investors in UK spinouts, says the stakes universities take in spinouts are rarely a barrier to the growth of early-stage companies. “What I consider most important is ensuring spinouts partner with investors that offer the right strategic support and follow-on funding to take companies into later rounds,” says Wright.

He adds that option pools, blocks of equity reserved for early employees of a company, can be a good way to reward founders. “It is also the role of investors and management to work together to effectively incentivise founders and management teams by providing reward through option pools,” he says.

As UK universities lower equity, they are being more creative with deal terms to offset lower shares. The University of Southampton balanced a smaller share in spinouts with higher royalty fees, similar to the US approach. Investors who were consulted on the decision to lower equity advised the university to look to the US as a good model to follow, says Woolley.

Universities should also not overblow the importance of revenue from equity stakes. The income that the University of Southampton earns from other sources such as sponsored research and facility fees dwarfs the amount it receives from selling shares and licence revenue, says Woolley.

Anne Lane, CEO of UCLB, the commerialisation arm of University College London, says the royalty-bearing licences it takes in spinouts are much more valuable than equity stakes. “Those licences can carry on generating income, even if they get licenced to another company. If a company goes bust and you’ve just got an equity stake in it, that’s it,” says Lane.

Investors, however, sometimes push back on royalty-bearing licences, especially for deep tech companies. This leaves technology transfer offices having to negotiate terms that work for everyone, says Steven Schooling, managing director of UCLB.

Efforts to bring university equity down across the UK are also hampered by stark regional differences in venture capital ecosystems. Spinouts from universities in London, the south east and east of England receive 74.5% of all spinout investment, according to a Russell Group briefing. Scotland receives 17%, while all other regions combined receive less than 10%. Universities in the so-called Golden Triangle of London, Cambridge and Oxford are particularly privileged when it comes to venture capital investment.

The University of Cambridge offer’s some of the UK’s most founder-friendly equity terms, taking between 5% and 20% depending on the technology and whether it is patented or not. The average equity it has taken over the past 10 years is 10%, says Paul Seabright, deputy director at the university’s commercialisation arm, Cambridge Enterprise.

But Seabright acknowledges that Cambridge is in a privileged position sitting in the centre of a well-developed VC ecosystem compared with other regions of the UK where university tech transfer offices have to do much more work to commercialise spinouts.

Creating spinouts in more deprived regions means “you’re going to have to do everything,” says Seabright. “You’ve got to coach and mentor the academics. You’ve probably got to buy out some of their teaching time. You’ve got to find investors, invest yourself, do all the patent work to make sure they have intellectual property assets. And if you are doing that, you don’t want to take cash out of company, so you are going to take a bigger equity percentage. I think that is perfectly reasonable,” he says.

Nevertheless, in the north of England, the pressure to reduce university ownership is filtering through to academic institutions. The University of Leeds is in line with the TenU recommendations for taking up to 25% for IP-based technologies, says Arshad Mairaj, head of ventures at the institution. It took share percentages in the single digits in two of its most recent spinouts deals after investors came in, he says.

This is despite the fact that the university faces a heavy lift when it comes to commercialising spinouts. “We spend a lot of time, energy and internal capital on proof of concept and making these opportunities ready,” says Mairaj, adding the university relies heavily on government funding to do proof-of-concept work.

Regional spinout funds help build ecosystem

New investment vehicles that pool university resources regionally are also helping to boost spinouts in more deprived regions. The universities of Leeds, Sheffield and Manchester in the north of England helped set up Northern Gritstone, an investment firm that primarily invests in spinouts from these universities. The firm and its co-investors have channelled £300m ($388m) into 19 spinouts since its founding in 2021. Each of the founding university partners has a small shareholding in the firm.

A similar investment vehicle is being set up in the UK Midlands, where eight universities have come together to establish Midlands Mindforge, which plans to invest in spinouts from the partner universities once it has secured investment.

A key part of attracting venture capital is university venture funds, which have helped to de-risk spinout funding. University College London, for example, has a £70m venture fund, UCL Technology Fund, that invests in the university’s spinouts as well as funding proof-of-concept and development projects. “It has made a big difference,” says Lane.

As momentum grows in the UK for lowering university equity and creating more favourable terms for founders, there are hopes that more VC capital will emerge for spinouts.

“Capital will follow the most favourable environments,” says Woolley at the University of Southampton. “Institutions will increasingly want to be seen as outward-looking and entrepreneurial, as an attractor of the best staff and brightest students.”