From needleless wearables that monitor glucose to thermal imaging that prevents amputations, spinouts are improving care for a disease that affects 550m people.

There were an average of 168 lower limb amputations per week in England between 2017 and 2020 — the latest available dataset — due to diabetes, according to the National Health Service (NHS), which also notes that 85% of these amputations are avoidable. There are an average of 2,900 such amputations in the US each week, the vast majority of these also due to diabetes.

Amputations are preceded by foot ulcers, common in diabetes patients as high glucose levels cause poor circulation and damaged nerves around the foot — hindering the body’s ability to fight infection.

Beyond the personal costs, foot amputations are also expensive for healthcare providers, costing up to $1.5 trillion worldwide by 2030, according to Queen’s University Belfast.

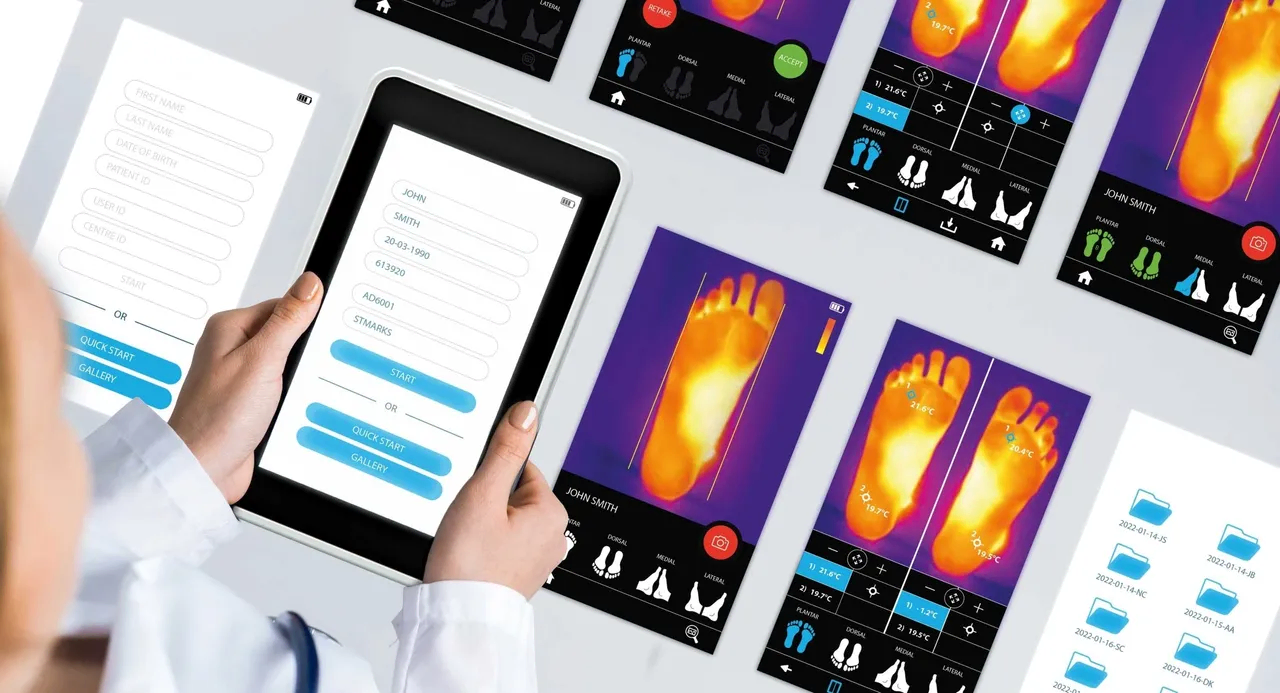

Thermology Health, a UK-based spinout from the National Physical Laboratory (NPL), hopes its invention can help. The company has developed a thermal imaging device that can measure skin temperature at an accuracy of ±0.2 degrees Celsius.

Foot ulcers have a subtle temperature difference compared to the rest of the foot and Thermology Health’s temperature imaging device can detect an ulcerative growth early, enabling preventative care before it leads to complications.

Yuval Yashiv, chief executive of Thermology Health, says foot ulcers affect “15% of diabetics, and the five-year prognosis following amputations leads to higher mortality rates than even cancer, at more than 30% over 5 years.”

Diabetic foot complications are a large cost-burden on the NHS, taking up almost 1% of its entire annual budget, adds Yashiv.

“Our technology’s accuracy of readings is what makes it stand out from our competitors and we also cover the whole foot rather than just the soles of the feet. We’re also offering a telehealth solution whereby patients will be able to monitor their feet at home, rather than by visiting a clinic,” says Yashiv.

Monitoring, prevention and tackling type 2 diabetes

Thermology Health is one of a number of startups working on new ideas for diabetes care, as an estimated 550 million people are living with one form of the disease. University of Bath’s Transdermal Diagnostics, for example, has developed a wearable smart patch that contains biosensors that sample fluid and cells on the skin.

A diabetic’s life is one of care and alertness — patients have to constantly monitor their sugar levels, eating habits and fitness to ensure that their glucose levels are stable.

A common practice for diabetics is to measure blood sugar to reduce dangers such as diabetic shock. This is done through finger prick testing or using a flash glucose monitor — but the downside of these practices is that they can be painful, invasive and difficult to learn. So it is no surprise that university spinouts have emerged to improve this aspect.

Transdermal Diagnostics’ needle-free, pain-free wearable aims to allow patients to manage their blood sugar levels and diabetes more accurately and effectively.

Luca Lipani, Transdermal Diagnostics’ chief executive and co-founder, explains: “Our main target is to help people with type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetes. We have noticed that the focus of diagnostic companies is on those with type 1 which is a fraction of the people who currently suffer from diabetes.”

The disparities between type 2 and type 1 diabetes healthcare support and innovation are apparent. Investment in type 2 diabetes is mainly focused on the prevention of the illness rather than management and treatment, meaning that wider forms of innovation are available to those who suffer from type 1 — although the cause for this form of the disease is unknown, it’s believed to be a combination of genetics and environmental factors.

Lipani continues: “The products available on the market, that are mainly catered for type 1 sufferers, are expensive too and need lower sensory implantation into the subdermal part of the skin so individuals with type 2 diabetes tend to not buy or self-fund towards continuous glucose monitors. So we want to tap into this market aiming at this demographic subgroup by offering affordable non-invasive technology.”

Transdermal Diagnostics, founded in 2021, raised a $1m seed round last year led by Qubis Innovation Fund, the investment vehicle of Queen’s University Belfast’s tech transfer arm Qubis. Innovate UK topped up the round with a $380,000 grant. Transdermal used the money to expand its engineering team and prepare for clinical trials.

A promising investment landscape for spinouts?

Diabetes is a huge opportunity for investors. Research by Data Bridge Markets put the diabetes care market value at $29bn in 2022 and projects it to grow to nearly $56.6bn by 2030. While type 2 diabetes — typically acquired through lifestyle choices like diet or lack of exercise — is by far the most common, there are 11 types of the disease — some 2% of all patients have a less common form of the disease.

Recent medical advances such as the development of semaglutide (sold as Ozempic, Wegovy and Rybelsus), a once-weekly injection used to improve blood sugar levels in adults with type 2 diabetes, have opened up new possibilities for treatment, but these are not suitable for everyone. There is still a need to improve other care options, and the American Diabetes Association notes that a lack of funding threatens the progress of diabetic research.

Lipani and Yashiv both say that investment into diabetes-related spinouts is increasing, but struggles to keep pace with the spread of the disease. “Investment is increasing because the market itself is increasing, so unfortunately as the disease grows the race to find noninvasive and reliable treatments begins,” says Lipani.

Phillippe De Backer, senior partner of Newton Biocapital, is one of the investors interested in backing startups in this area. “Healthcare and diabetic spinouts have a significant impact on people’s lives and a huge potential for success,” he says. “It also represents a significant business opportunity with the potential for high returns on investment.”

Newton Biocapital’s portfolio includes AdipoPharma, a France-based developer of adipocytes that target insulin resistance. The INSERM spinout closed a series A round of undisclosed size in January this year.

“Diabetes startups such as AdipoPharma can bring new ideas and technologies to market, using their agility and entrepreneurial spirit to develop innovative solutions that address unmet needs. That is why we invest in them,” says De Backer.

Finding truly innovative new startups to back, however, is one of the challenges.

“There is massive competition in the diabetes space so finding a spinout that is truly unique plays a part,” says De Backer. “University spinoffs remain an important source of innovation in the diabetes sector, as they can leverage the expertise and research capabilities of academic institutions to develop new and innovative solutions.”

Some universities have specialised departments for diabetes research, such as the Exeter Centre of Diabetes Research at the University of Exeter.

Yashiv notes that the fundamental research conducted at universities gives spinouts an edge over other commercial companies. “A second advantage is the timeline element, which is longer within a university environment than it is in a commercial environment,” he says.

However, there are some concerns that diabetes research programmes are too dependent on short-term funding patches. The lack of permanent funding stalls innovation and new research, according to Cardiovascular Business, the healthcare-focused media company.

Some government funding can help. Thermology Health, for example, received an undisclosed sum from the UK’s Government Office of Technology Transfer, which provided a knowledge asset grant to the National Physical Laboratory to commercialise the technology.

“NPL is where this technology was developed and they remain a key and active partner. NPL has spent quite some time developing this technology and is committed to helping Thermology even after the spin out. This creates a lot of synergy and makes it an even more attractive proposition,” says Yashiv.

Next steps: more collaboration

The other challenge with diabetes spinouts is the perennial problem of university spinoffs — commercialising them successfully.

“At some point, a project needs to take on a practical turn and move from theory into practice,” says Yashiv. “This is where, quite often, academics fail. A technology needs to turn into something that can be commercialised and work in the real world and at scale, otherwise, it remains an academic or R&D project. The more emphasis there is on this stage, the more investable the spinout is.”

Lipani believes that universities need to be aware of the diabetes markets and a spinout’s journey beyond incorporating the business. “The universities have to facilitate the process of spinning out in such a way that makes the company and founders more investable. They also should be willing to continue this journey with us after spinning out because the medical device sector is very competitive and support from an institution would go a long way,” says Lipani.

De Backer also believes that universities should go further. “In Europe, universities could play a greater role in addressing major societal challenges,” he says. “Encouraged by the European Union, national governments and universities could join forces with the private sector, including investors, to help decide the best approach to solving these societal problems.”

He concludes: “As diabetes is a growing problem of quasi-epidemic proportions, directing more private and public investment could help find solutions. Second, universities should facilitate faster spinout companies to give every chance of bringing a new product to patients as quickly as possible.”