Japan has a well-funded and vibrant market for deep tech companies spun out of its universities. Here are some of the quirks that foreign investors seeking to dip a toe into the sector should look out for.

Japan has one of the most sophisticated university spinout ecosystems in Asia, and has seen the number of spinouts receiving funding grow 10-fold in the past decade. It is a potentially attractive sector for foreign investment, with strengths in deep tech areas such as semiconductors, materials science, quantum computing and aerospace technologies.

But Japanese spinouts still receive relatively little foreign investment — something the government would like to change. Here are some of the untapped opportunities — and some of the challenges — that potential foreign investors should be aware of.

1. A small but rapidly growing ecosystem

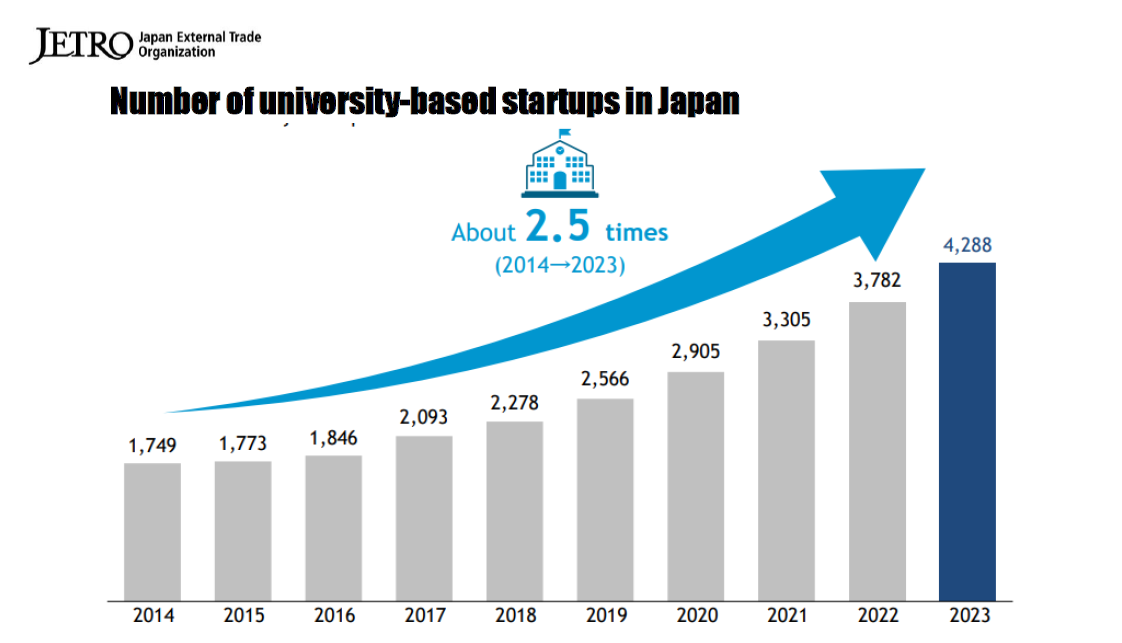

The number of spinouts in Japan has increased two-and-a-half times over the past 10 years, reaching 4,288 in 2023, according to data from the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO).

In 2023, 426 spinouts received investment, according to Japanese VC data provider Initial. This is almost 10 times the total investment that spinouts received in 2014.

Despite the growth, Japan’s overall venture capital ecosystem remains small compared with other countries. It is only 3% of the US market, for example. The government is keen to boost foreign investment in its startup sector. The capital, Tokyo, is positioning itself as a startup hub. The city government aims for a tenfold increase in the number of unicorns and startups in its ecosystem.

2. It is a well-funded ecosystem at the pre-seed level

Japan is an outlier among Asian countries for its network of university-affiliated venture funds. Eighty-five percent of its top academic institutions have an investment vehicle to support spinouts and startups, according to Global University research. This has helped to boost the commercialisation of university research.

The country has one of the biggest university investment funds in the world. The University of Tokyo has two investment vehicles: the Innovation Platform (UTokyo IPC) with $420m under management and University of Tokyo Edge Capital Partners (UTEC) with $594m. This gives the university a combined capital resource of just over $1bn, almost the size of the largest university-affiliated fund in the world, the University of Oxford’s Oxford Science Enterprise, which has $1.1bn.

The University of Tokyo Edge Capital Partners is one of the oldest, continuously running university venture funds in the world. It was set up in 2004, 10 years before the Japanese government increased spinout investment and allocated capital to other academic institutions to set up funds.

Read more

Japan is fund leader among Asian universities

3. Government supports spinouts financially at earliest stages

The Japanese government also plays a crucial role in funding academic research before it is spun out into companies. The country’s national research and development body, Japan Science and Technology Agency, runs a funding programme called START, aimed at commercialising technologies from Japan’s universities.

The initiative brings together university researchers and venture capital firms to commercialise research, with the government providing non-dilutive financing before a company is formed. Japanese VC firms participating in the programme include Jafco, Angel Bridge, Beyond Next Ventures and ANRI.

4. But it lacks later-stage venture capital for deep tech startups

Deep tech research is particularly strong in Japan, but, despite having plenty of funding at the early stages of company creation, the country lacks venture capital to back its deep tech spinouts at the series A stage and beyond. Like the UK, which also is a leader in spinout creation, domestic capital for later stage funding is not readily available.

The average size a series A funding round in Japan is only $5m, a fraction of what is raised at that stage by startups in the US.

5. Japan’s universities tend to take low equity stakes in spinouts

Academic institutions taking large portions of equity in spinouts is not that much of an issue for investors in Japan. It is more the norm for universities to take ownership positions of up to 20%.

High ownerships stakes are barriers to investment in other countries with active spinout sectors, such as Australia and the UK, although these jurisdictions are coming under increased pressure to lower their ownership shares in spinouts to below 25%.

6. But there can be roadblocks with the ownership of patents

It is often unclear to what extent Japanese universities own patents in university research. “Universities need to be more professionalised about their patents,” says Ken Kajii, general partner Japanese venture capital firm Global Brain. “They should make it clear who owns the patent and to what extent,” says Kajii, whose firm invests in the country’s spinouts.

“If it is vague, it is going to be difficult for us to invest in. The rules need to be defined.”

Adding to the problem is the fact that each university has a different approach to transferring the ownership of patents. Although universities are willing to transfer patent ownership, the lack of a standard approach to terms and conditions can put off investors, says Kajii.

7. Corporates can also pose a barrier to spinout investment

Another potential challenge for investors is that Japanese corporations will often have control of the intellectual property of research originating from universities. A lot of research and development at Japanese universities is done in collaboration with Japanese corporations.

“The sticky part about that is when there are patents that get filed as a result of these collaborative research projects. It tends to have both the university and the corporate as holding rights to the patent,” says Kiichiro DeLuca, partner at Weru Investment, a venture capital firm which invests in spinouts from Waseda University and other Japanese academic institutions.

“Sometimes that can end up being a roadblock to a spinout company being formed because the corporate isn’t as enthusiastic about it being commercialised by an entity that falls outside of their organisation,” says DeLuca.

8. Japan lacks incubators to support business creation

Although Japan has academic researchers with deep technical knowledge, it lacks people with business skills to lead commercial companies emerging out of the research.

“The more technology-heavy startups here are going to have personnel who are not as well versed in operating in a global business environment. These are people who have really focused on their research and their technology for much of their career,” says DeLuca.

The lack of business talent and founders that have a global outlook can make it difficult for foreign investors to work with deep tech spinouts.

The shortage of incubators and accelerators that pass on knowledge to academic founders for how to run a business is part of the problem. A lot of incubation work is done by technology transfer offices, but people who work there are more trained in licensing patents than imparting the skills needed to run a company.

Venture capital firms that invest in academic research have had more success in this area. Global Brain, for example, hires a business professional to help run a deep tech spinout or startup that it has invested in.