- News & Analysis

- Home

- Global Corporate Venturing

- Global University Venturing

- Latest News

- Publications

- Podcast

- The CVC Funding Round Database

- The CVC Directory

- Video

- Subscribe

- Newsletters

- Events

ContentsFeature: India’s shift from consumer to deeptech attracts a new wave of corporate investorsViews: Investor viewsStartups to watch: Indian startups to watchFeature: India’s booming spacetech sector offers opportunities for investorsFeature: Global investors line up for India’s EV explosionBy Maija Palmer, Anamya Anurag and Kaloyan Andonov

India’s shift from consumer to deeptech attracts a new wave of corporate investorsThe country’s hard tech startup sector is a magnet for investment despite an overall slowdown.

Startups and venture capital boomed in India over the past 10 years with big companies in the consumer and financial sectors — names like fintech company PayTM, ecommerce operator Flipkart, edtech company Byju’s — becoming not just unicorns with valuations of $1bn, but “decacorns” with valuations in the tens of billions.

The past year has taken some of the shine off that. Amid a general global slowdown in investment activity India has seen one of the sharpest falls, with new startup funding rounds in 2023 down 39% from the previous years.

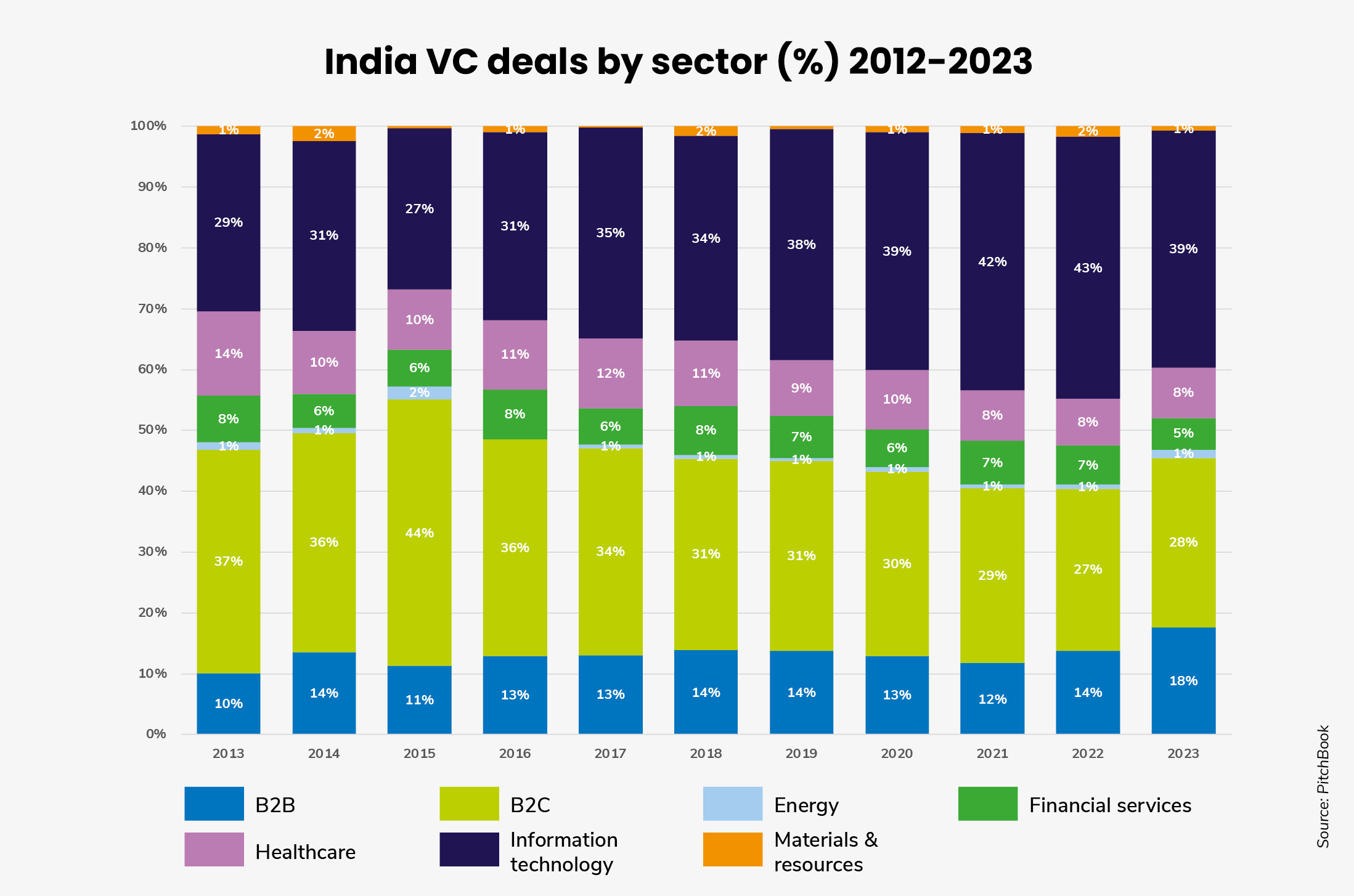

But, say investors, the headline numbers don’t tell the whole story. Beneath the declines for investment in consumer-related startups, a new cohort of more science-based and industrial-focused startups — in areas like AI, energy and mobility — is starting to grow and attract investment.

“If you are in the traditional space of maybe payments or fintech, e-commerce or gaming or education, that’s where the struggle is,” says Siddharth Mehta, investment director for TDK Ventures’ India operations. “But here is no dearth of capital for a deeptech company raising capital, even at this point.

“But there is no dearth of capital for a deeptech company raising capital, even at this point.”

Siddharth Mehta, investment director for TDK Ventures’ India operations

“Consumer and fintech startups were the low-hanging fruits, which are naturally the first targets for entrepreneurs. But now we are turning to harder problems with the growth of deeptech startups,” says Rama Bethmangalkar, director at Qualcomm Ventures, and an investor in India since 2007.

The emerging deeptech companies are attracting a new group of industrial-focused corporate investors to India.

“India is building for the world,” says Rajiv Mukherjee, chief evangelist at Bangalore-based venture studio IncubateHub.

“Experimentation is happening in India, quick experimentation, for companies that may be headquartered in Europe or elsewhere. If a Daimler is trying to launch a car in Germany, they are solving their most difficult problems with startups in India. That’s something that we are clearly able to see,” he says.

“Initially, India was looked upon as a low-cost destination for companies to find talent, but it graduated to become an innovation hub,” he says.

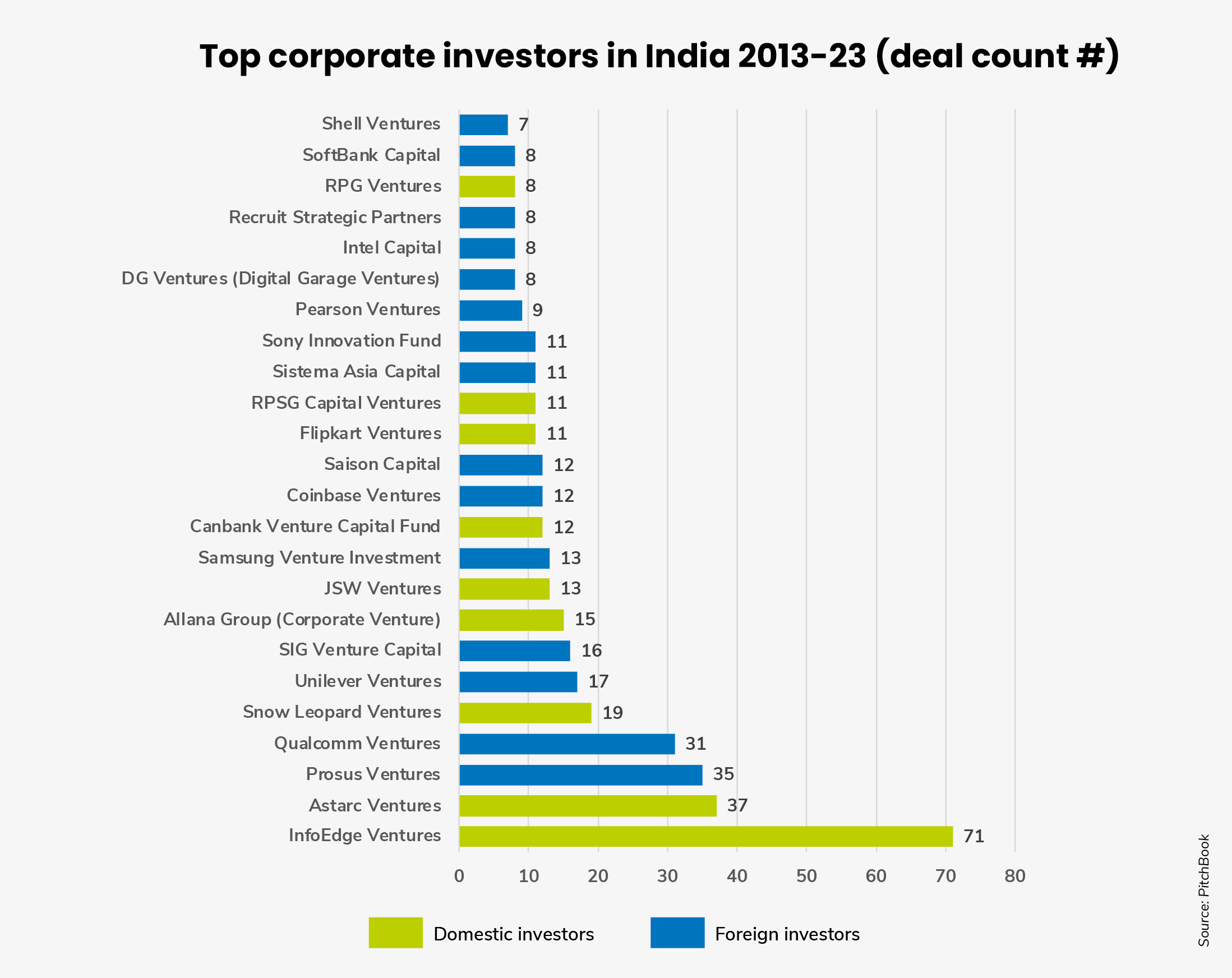

IncubateHub works with corporations to help them find startups to invest in or partner with in India. Mukherjee says he now works with around 110 such corporates — partly from abroad and partly in India. Back in 2014, when he first set up IncubateHub, just four corporate investors were active in the Indian market.

Vinay Subramanian is seeing the same trend. Subramanian helped build one of the first a corporate venturing arm for Indian e-commerce group Flipkart in the early 2010s. Now an academic at Wharton Business School, he still advises people interested in entering the Indian market.

“A lot of people come to me from EV companies, battery management companies, and say they would like to allocate some capital and have a unit in India. That’s a conversation I’ve had with a number of people. In the last couple of years, it has mushroomed. I don’t know if they are deals, but certainly there are teams that are coming to India,” he says.

Growth of the Indian VC market

India’s startup growth was kicked off by a large government digitalisation project, starting in 2010, which involved, among other things, issuing of unique digital identification numbers to citizens. This opened up possibilities to bring financial services to people who had previously been unbanked. Fintech startups such as PayTM grew rapidly. There was also large appetite for educational tech among a population that in places lacked access to schools and teachers. Startups such as Byju’s saw exponential growth.

“Because of the digital infrastructure a lot of innovation happened in the financial domain. A lot of startups got built there. Then, the other sectors like CPG [consumer packaged goods], retail and mobility came into the fore,” says Mukherjee.

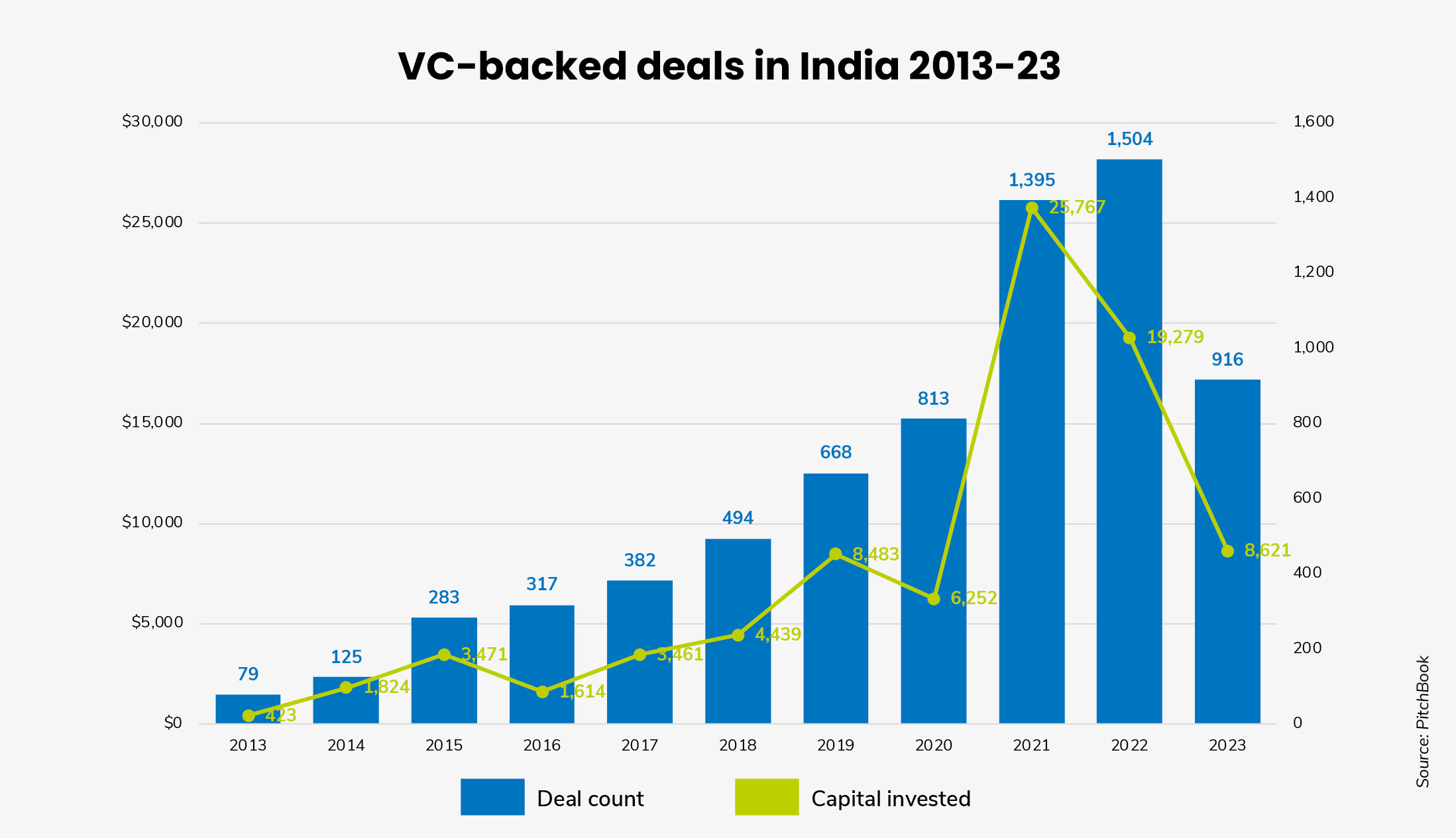

India began to see rapid growth in venture capital investment starting in 2013 and 2014. Startup funding rounds went to 1,504 at the peak of the market in 2022 from 79 in 2013. The total estimated dollar value of these VC funding rounds also grew multifold – up to a maximum of $25.77bn in 2021 from $423m in 2013. Even though funding declined last year — as it has done globally — VC activity was still higher in 2023 than it was in 2020, before the boom years.

The number of startups has grown more than 15-fold to more than 100,000, according to Invest India, an investment promotion organisation.

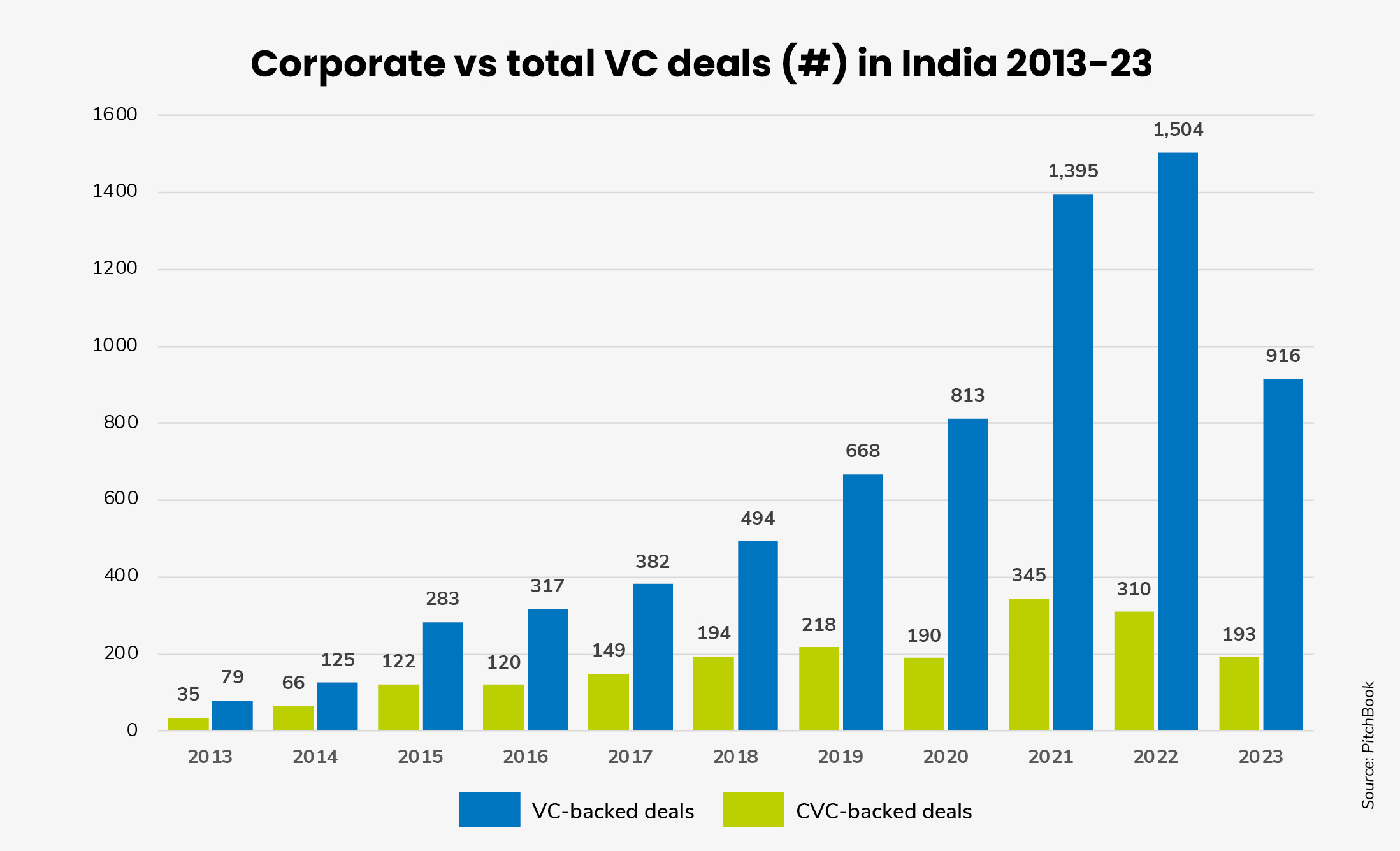

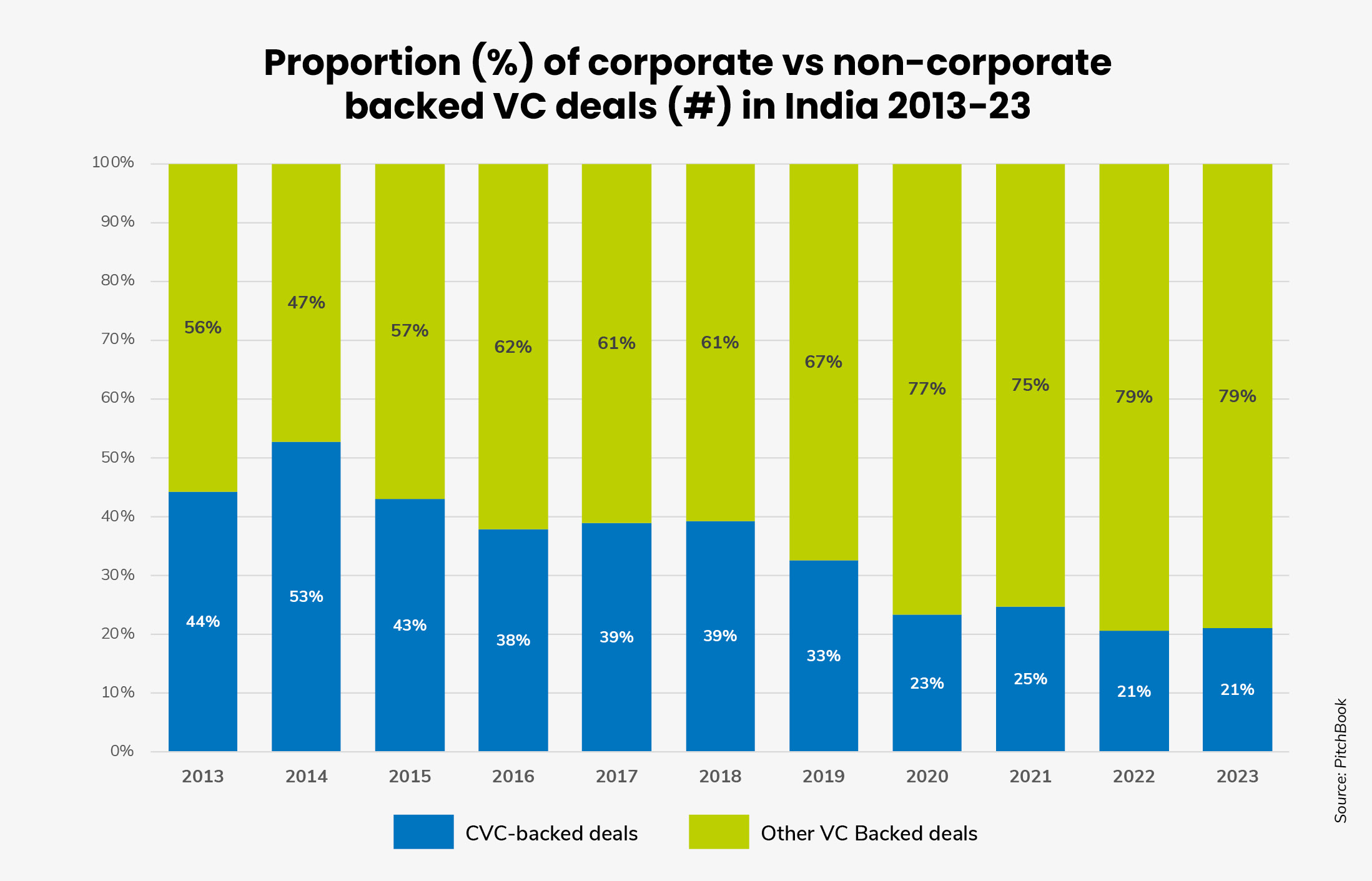

Corporate venture investors have also seen growth in numbers. They have gone from backing just 35 rounds in 2013 to taking part in 345 in 2021, falling back to 193 last year. In the early days, corporate venture investors were a key source of capital in a nascent market, says Subramanian.

“In the early stages we were standing for institutional VC because India didn’t yet have a lot of VC capital. 2012-13 was when the first startup boom happened. There was some capital, but I’d say there was a vacuum in institutional capital,” he says.

Corporate venture capital remains a fairly large part of the market. In the early days of India’s startup boom, corporatebacked funding rounds accounted for around 40% of half of all the fundraising deals. Even in 2023, they still accounted for 20% of all deals.

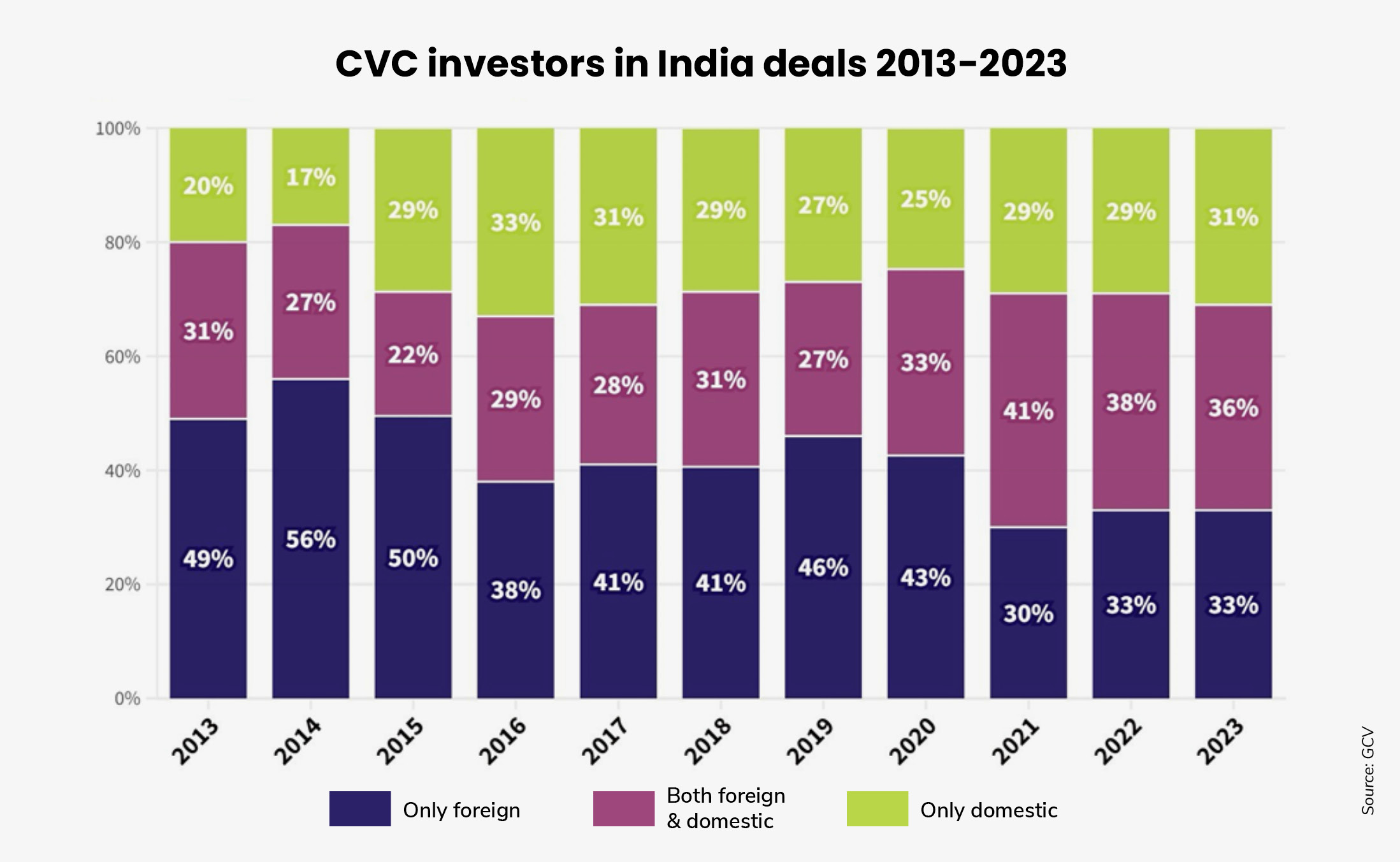

The corporate VC crowd has become diverse over time. Between 2013 and 2015, half or more of the corporate backers of Indian startups were foreign corporations, while only about 20% of the rounds featured Indian corporates only, as the GCV data suggest. Today, nearly a third of rounds feature domestic corporate backers only and another third foreign corporates only.

Now might be becoming an even better time to be a corporate investor in India, says Mukherjee.

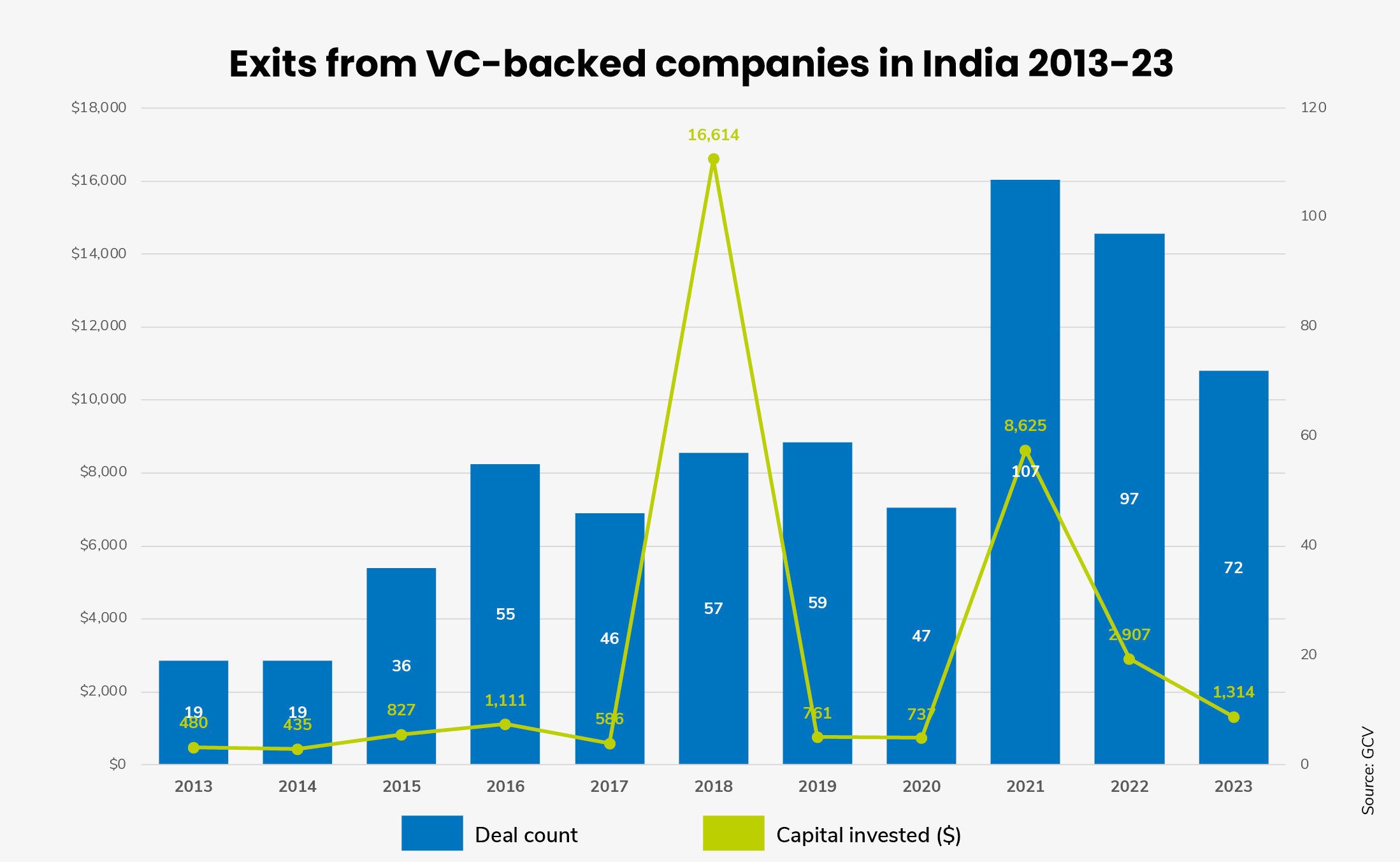

Much like everywhere else globally, exits by VC investors have fallen in India in the past year. The 72 exits achieved in 2023 was a 33% drop from the peak of 2021, although it was still higher than levels seen prior to 2020.

But a more constrained VC market may leave more options open for corporate investors that still have capital to deploy.

“Corporate capital has been waiting patiently, just looking at VCs putting in money at crazy valuation. And now they will have the last laugh. Right now, there are many opportunities to acquire or put in money at the right valuation. The traditional VCs are losing out, but the CVCs will benefit,” Mukherjee says.

Shift to deeptech

Consumer sector startups still dominate the VC sector in India. Even in 2023 some 28% of all startup funding rounds went to consumer sector companies. IT services also makes up the bulk of rounds. But this is gradually starting to change.

When Mehta founded energy company Shell’s innovation hub in India in 2017-2018, there were barely any investors putting money into deeptech startups in India. It took him a year even to convince Shell to invest in its first startup in India.

“We were early flag bearers in climate and industrial tech,” he says. But after that first investment, further Shell deals came quickly, with the energy company investing in power plant builder Husk Power Systems, ride hailing app Rapido and industrial AI provider Detect Technologies. Oil major BP also came into the market in 2021, investing heavily in BluSmart, an electric vehicle ride hailing company, as well as in EV charging network Magenta. In 2022 Mehta moved to TDK Ventures, to help the Japan headquartered electronics company set up a unit in India.

Mehta says India’s strength in digitalisation has exciting applications for industrial companies. “Especially now with generative AI coming in, we can see industrial applications for that. This is one area where I’m super excited about the future of India.”

Electric mobility, batteries and hydrogen are also areas where Mehta says India is making rapid progress.

Last year TDK made its first foray into the Indian EV market by joining the series B round for battery company Exponent Energy. It also invested in Infinite Uptime, a Pune-based company that uses AI for remote predictive maintenance of industrial machinery.

Mehta and Bethmangalkar at Qualcomm are also watching for opportunities as India begins to build a homegrown semiconductor industry. This is an area that the government is keen to push and where India should have the required talent.

“We have tens of thousands of engineers who design semiconductors, but hardly any assembly, packaging or manufacturing companies,” says Bethmangalkar. Qualcomm Ventures recently invested in a small startup in the semiconductor sector, involved in the packaging and module making side. Belthmangalkar says the company’s products are being very well received in North America and Europe, in part because geopolitical tensions between China and the West are causing people to rethink their semiconductor supplier arrangements.

Indian semiconductor companies have the advantage of being less likely to be subject to sanctions by western governments.

To keep an even closer eye on deeptech innovatons coming out of India, TDK plans to open an innovation hub in partnership with the Indian Institute of Technology Madras, a public technical university located in Chennai.

“That a Japanese company is even thinking of putting up an incubation cell in a research institute like IIT Madras in India speaks volume of the kind of talent and skill they are seeing,” he says.

Financial VCs are also starting to catch up with the trend to invest in engineering and science-based companies in India.

“Now we have specialised financial VCs investing in deeptech companies. Sequoia invested in a battery recycling company and a hydrogen company. Then we have Indian VC firms, large ones, who are investing in new technologies. Some of them are really specialising in tech investing,” says Mehta.

What investors need to know about working in India

“India has a mind of its own,” says Parag Shah, who has been with the Mahindra Group, a car manufacturer, for more than 25 years. “You can’t assume that if it’s worked elsewhere it will work in India.”

Shah says investors coming into the Indian market need to understand its nuances. A two-level market operates in India – the urban market which makes up a small percentage of the large population and the semi-urban rural market. As an investor, finding consumers in a country with a population of 1.4 billion people is easy, but finding the target market involves an elegant strategy of “slicing and dicing” to find the right mix of digital and brick-and-mortar-focused startups.

Similarly, investors and entrepreneurs must take into account that premium prices do not have a place in the Indian market yet, one of the most important factors influencing choice is still the price of a product, with most seeking “best value”.

“The important thing is we should not map a Western thesis onto India,” says Mehta. India is good at very frugal innovation — you can probably achieve the same results with a third or a quarter of the capital you would need elsewhere for launching and testing a product in the market.

“What you can achieve in India for the same amount of money is so much more than you can in any other part of the world. For a third or a quarter of the capital you can get an excellent test bed for multiple solutions.”

But at the same time, because there is very little government support for research and development — in the way you might have in Europe or even the US — India is less likely to have startups that require long development periods before going to market.

Finding the good technology companies will also take time, says Subramanian. “You need patience. Let’s say you have an expectation to invest $50m of capital every year. It’s not going to happen overnight. You probably need to have your team on the ground for five to 10 years. You won’t just come in and find 100 good battery companies in Bangalore. It’s going to take time finding those diamonds in the rough.”

Investors who are coming to India for the first time, should also pay attention to “cultural alignment” says Shah. He believes Indian founders tend to be more “emotionally attached” to their business, and paying heed to that is important for collaboration.

Healthcare | Human microbiome

Publications | Reports | GCV

Read the full report on your tablet or device.Download PDFAbout us

GCV provides the global corporate venturing community and their ecosystem partners with the information, insights and access needed to drive impactful open innovation. Across our three services - News & Analysis, Community & Events, and the GCV Institute - we create a network-rich environment for global innovation and capital to meet and thrive. At the heart of our community sits the GCV Leadership Society, providing privileged access to all our services and resources.

Navigation

test reg

test regLogin

Not yet subscribed?

This website uses cookies to improve your experience. We'll assume you're ok with this, but you can opt-out if you wish.Accept Read MorePrivacy & Cookies PolicyPrivacy Overview

This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website. Out of these, the cookies that are categorized as necessary are stored on your browser as they are essential for the working of basic functionalities of the website. We also use third-party cookies that help us analyze and understand how you use this website. These cookies will be stored in your browser only with your consent. You also have the option to opt-out of these cookies. But opting out of some of these cookies may affect your browsing experience.Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. These cookies do not store any personal information.Any cookies that may not be particularly necessary for the website to function and is used specifically to collect user personal data via analytics, ads, other embedded contents are termed as non-necessary cookies. It is mandatory to procure user consent prior to running these cookies on your website.