Companies that struggle with early corporate venturing efforts will often turn to CVC-as-a-service, says Bill Reichert of Pegasus Ventures.

“If you think innovation is going to be important to your company, or if you think any of your business units are at risk of disruption by innovation, then we should talk,” Bill Reichert, partner at California-based venture capital-as-a-service firm Pegasus Tech Ventures, says on an episode of the Global Venturing Review podcast.

Firms like Pegasus, says Reichert, represent the latest iteration of corporate venture capital, calling it CVC 4.0, following previous generations that include corporates investing through their own units (3.0) and traditional VCs bringing corporates on as limited partners (2.0).

CVC as a service has seen a strong increase in popularity over the past few years, driven in large part by the necessity companies have to innovate to grow, as well as by the threats of obsolescence.

“Corporations come to us with these sort of two burning issues. One is the generic issue of growth. How do I grow? And the other is a series of different specific issues around: this business is threatened, this business is threatened, this business is threatened. I’ve got to make sure that we either move to the head of the pack or find a different business that can leverage our core competencies,” he says.

A third element corporates want to figure out is how to instill a culture of innovation and the mindset to go along with it. That can run into trouble, however, when companies go out and look for innovation only to come back and be shot down by business unit managers who may be focused on shorter-term objectives.

Getting to know each other

No two clients are the same. Coming from different sectors and bringing different needs, a strategy has to be formulated for each one, requiring Pegasus to gain a deep knowledge of the corporate.

“Cultures are different, organisational structures are different, obviously business sectors are different, but what we do is we get to know each other well enough that we can then invite the business unit managers and the key senior people in the company into a series of workshops that we do. We call it Pegasus University,” explains Reichert.

Humans are humans, some business unit managers are more receptive than others.

The general aim of Pegasus University is not just to get to know them, but to get the various organs of the company on board with it all – from the CEO to the business units – so that they get the feeling that they are a part of this innovation shift and become more receptive to it.

Reichert says: “A key aspect is to get the business units sort of explicitly motivated to participate. One of the things we’ve learned is that just because humans are humans, some business unit managers are more receptive than others. What you learn is to go with the ones that are receptive and don’t try to change people. Let them come to you. Don’t impose upon them.”

Getting everyone on board doesn’t necessarily mean fixing everything all at once, though. This is especially true with larger corporates that have more business units. A more measured approach tends to be preferable.

“Usually when we start out, the team on the corporate side that is driving this has identified some business unit technology sectors that they are most focused on. Generally, we encourage starting with sort of a limited scope and not trying to fix the entire corporation,” he explains.

“Some of our corporate partners, they’ve got 11 different business units. That’s somewhat challenging for everyone to cope with 11 different mandates. Generally, what we want to do is start in an area where hopefully there’s some low-hanging fruit where there’s the highest receptivity and the highest need.”

Range of clients:

“If you look across all the corporates that we’re working with, it’s a spectrum from those who are brand new to the idea of open innovation and working with startups, to those who have been doing it through some form of corporate innovation and corporate venturing group for many years,” says Reichert. He adds it’s typically easier to work with those that are already familiar with corporate venturing.

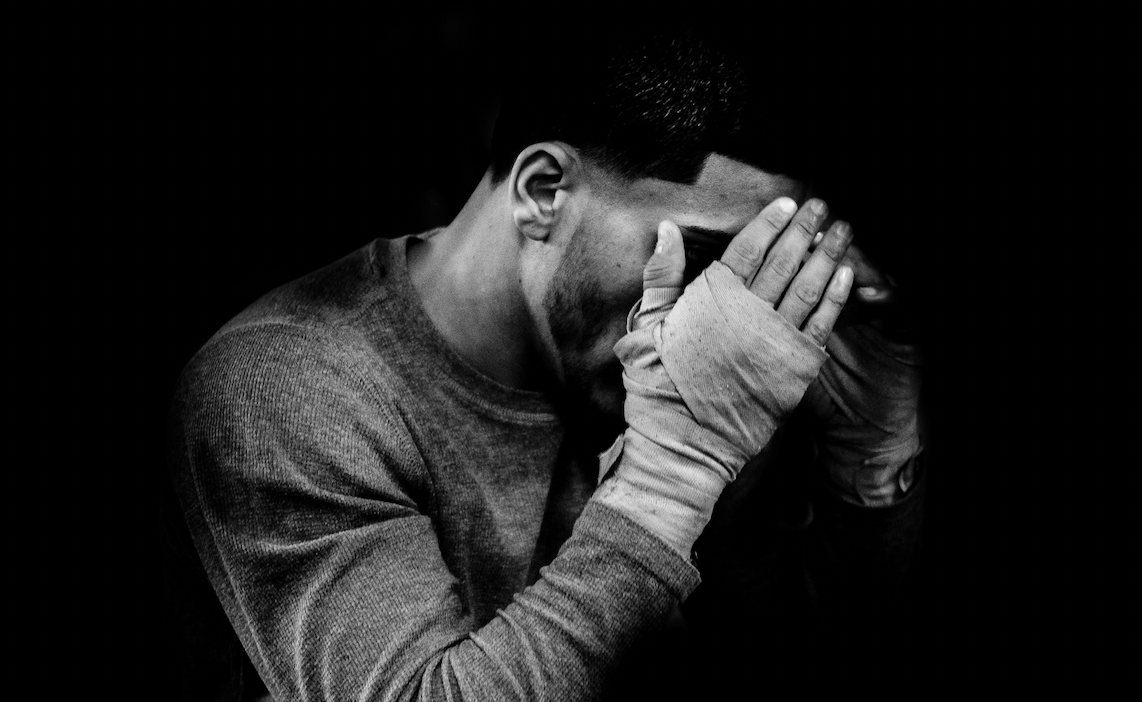

The ones that have been doing it for a few years, they’ve been whacked in the face.

“The ones that have been doing it for a few years, they’ve been whacked in the face. They know what they don’t know and so they see us not as a replacement for what they’re doing, but as an extension of what they want to do.”

Naturally, coming in to help a CVC that’s struggling to reach its potential can potentially lead to friction. A focus on aligning objectives and strategies – getting on the same page – works to mitigate this risk.

“So, generally, it winds up being sort of a very top, CEO-level sort of discussion about how can we extend our activity to be more productive, rather than a suggestion that it hasn’t worked or it has failed. It’s the suggestion of now let’s see what the next step is. There are some nuances to that evolution as you can certainly imagine, but we wanna plug in with the team, we never want to be in a situation where there’s any sort of adversarial situation within one of our corporate partners,” he says.

Don’t be afraid to fail

One of the more encouraging signs that Pegasus can see in a corporate partner is a willingness to take risks that may not pan out. A company that can engage with an interesting company or technology, and decide after a proof of concept that it wouldn’t work, is a good thing.

Most of those things will not work and that’s not bad.

“A big problem in corporate cultures is anytime any manager gets budget to try something, if that doesn’t work out in a bunch of corporate cultures – you spent money to try something and it didn’t work out – that’s a failure, right? And that’s a terrible mindset to have.”

“It’s really important to get the corporation to say it’s okay to try a lot of things, and we know that most of those things will not work and that’s not bad. That’s good. That’s a learning.”

That kind of failure-friendly mindset is not typical of your average corporation and requires buy-in from the top levels of the company. It doesn’t just apply to the R&D activities, says Reichert, but all over the company.

“A lot of corporations, their first step is to go hire a consultant,” says Reichert, explaining that consultants can come in with great graphs, theory and frameworks to teach about innovation, which could be useful but not as good as actually getting stuck in. That doesn’t mean that you throw caution to the wind and invest in 10 companies at once, but rather an iterative process with a few investments or collaborations at a time.

“Having a consultant sort of teach you innovation theory could be valuable for mindset, but the only way you’re going to really learn is by doing. And that’s the whole idea behind Pegasus, to help corporations discover, learn, grow and innovate.”

Fernando Moncada Rivera

Fernando Moncada Rivera is a reporter at Global Corporate Venturing and also host of the CVC Unplugged podcast.