Spinout creation rates vary wildly at universities and intelligent capital and corporate partners have a big role in changing the numbers.

Universities and national research labs are full of groundbreaking discoveries — but are we doing a good enough job of commercialising that research and turning it into companies and products that wider society could benefit from?

Some 1197 spinouts were created globally in 2021 and university spinouts raised some $25.4bn in funding last year. At the top end, the University of California system creates more than 80 spinouts each year, and other, high-performing university systems, such as those around Harvard, MIT and the University of Texas are creating 20+ spinouts annually.

But many other universities produce nothing near this number and there are vast differences between regions. The US and Canada produced 1121 university spinouts in 2021, while Europe produced 612. Japan had just 77 — although these numbers are from 2019, the last year for which figures were available.

Universities and national research labs should be a treasure trove for investors. The US government spends $42bn on backing university research each year and a further $6bn on backing national labs. This is a phenomenal R&D budget that entrepreneurs and corporations could be tapping into.

“It is easy finding people to play CTOs but there is a problem with finding entrepreneurial talent.”

Tom Vanhoutte

Universities and labs are particularly good places to find deeptech startups with easy-to-defend competitive advantage, says Tom Vanhoutte, partner at Imec.xpand, the venture capital fund started by Belgian nanotechnology research centre Imec.

“Deeptech can give you IP protection,” he says. “We like companies that are strongly rooted in technology [and] have a strong IP position, which means that the first setback they have does not mean it’s the end of the company.”

With some 48% of corporate investors interested in investing in companies at seed and pre-seed stage according to the last Global Corporate Venturing annual survey, there should, in theory, be growing interest in university spinouts.

But barriers exist: attracting skilled entrepreneurs who can turn research ideas into companies, is one key problem.

“It is easy finding people to play CTOs but there is a problem with finding entrepreneurial talent, people who can translate an idea into a product,” says Vanhoutte.

Supporting fledgeling companies through the “valley of death” years where there is no product or revenue yet is another.

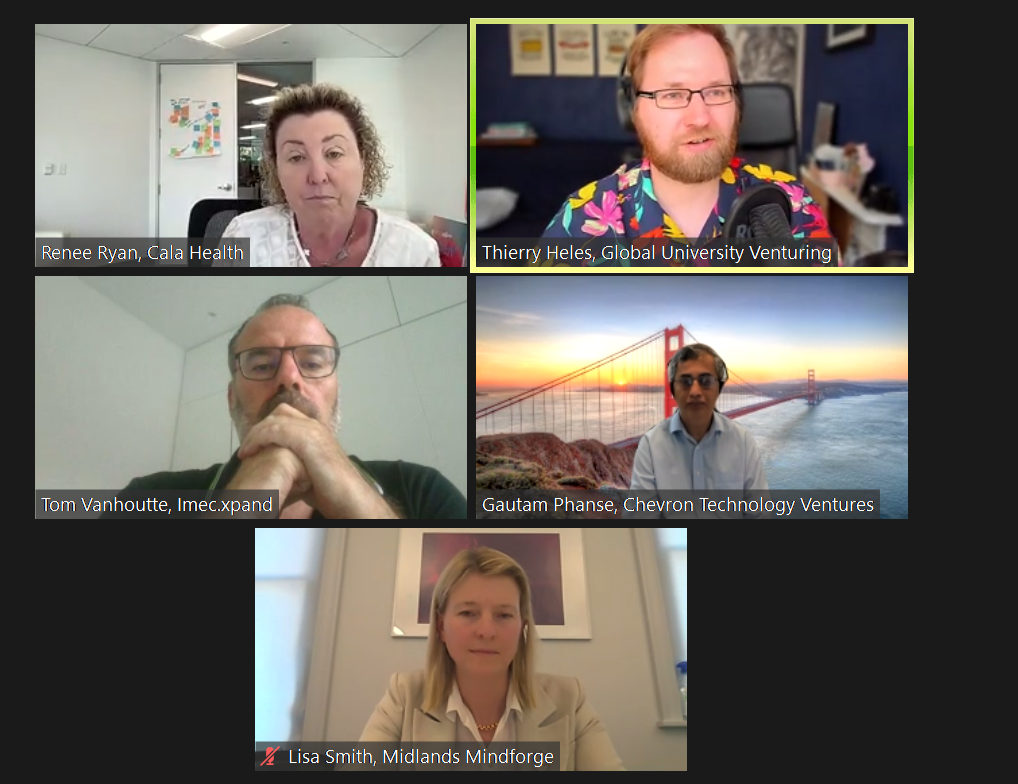

But university investment funds and savvy corporate investors can play a role in dramatically increasing spinout numbers and success rates. This week’s GCV webinar on engaging with university spinouts brought together four experts with views on best practice. In addition to Vanhoutte, these included Renee Ryan, CEO of Stanford spinout Cala Health, which is creating a wearable device to help patients suffering from essential tremors, Lisa Smith, CEO at Midlands Mindforge, a UK-based venture capital fund backed by eight universities in the Midlands region, and Gautam Phanse of Chevron Technology Ventures (CTV), the corporate venturing arm of the energy company. CTV has run the Chevron Studio program since 2021, which helps researchers at US national labs and universities commercialise promising lab innovations with the help of Chevron’s own business experts and a network of entrepreneurs.

This was some of the key advice and learnings that came out of the discussion.

1. Think beyond raw IP

Good university tech transfer offices go a long way beyond just circulating lists of IP to potential entrepreneurs and investors, says Cala Health’s Ryan. Before taking on the CEO role at Cala Health she was an investor at JJDC, the venture arm of pharmaceuticals company Johnson & Johnson, and she has seen growing sophistication by universities in helping de-risk spinout ideas from an early stage.

“I’ve seen a really strong maturity developed specifically in the healthcare field, in particular, […] tech transfer offices know that they can’t just send out a list of IP, and say it’s up for grabs. They’ve been able to identify those things that are truly translational, not just curing cancer in a mouse, but something that can move into the human realm,” says Ryan. “They put money around it, they put business plans around it.”

2. Simplifying spinout processes can make a big difference

This may sound basic, but small things that remove the friction from creating a university spinout can really increase the number of emerging companies. For example, Imec.xpand cut the amount of time it took to negotiate the IP rights for a spinout from eight to ten months, down to a quarter of that time, says Vanhoutte.

“If your goal is to do 20 plus deals, you have to avoid every deal itself being an event,” says Vanhoutte.

It can also help to put in place support systems of experts to help many of the new spinout companies with tasks like finance, marketing and hiring. Creating a spinout requires a new skillset that academic founders won’t necessarily have, and this can put them off going down the company formation route.

“We actually need great experts and a whole pile of different things that the startups can’t afford to hire full-time,” says Smith at Midlands Mindforge. That is why she is trying to create a shared resource for these kinds of specialised experts that spinouts can tap into. She says. “If you have a fund that’s operating at sufficient scale, you’re actually able to supply that kind of resource on an hourly basis. That unlocks some of the barriers to scale.”

3. Remove the stigma of commercialisation

It is still hard to convince academic researchers that commercialising technology is a worthwhile exercise, says Smith.

There is still a journey to be undertaken in “changing the slightly dirty feel of commercialising IP into something of bringing groundbreaking innovation and solutions to the world”, she says, and “changing the culture around that.”

4. Find creative ways to bring in entrepreneurs

Pairing academics with entrepreneurs is crucial in creating successful businesses, but attracting that kind of business talent in is a problem, universally. It was one of the biggest issues each panelist grappled with from Vanhoutte at Imec.xpand strugging to get people to relocate to Belgium, to Cala Health facing the fierce war for talent in Silicon Valley. Ryan actually took on the role of CEO at Cala Health in 2019 because it had been so difficult to find someone with both healthcare and business experience to lead the company.

Mindforge’s Smith is looking to entice talented entrepreneurs to the Midlands by offering “ridiculously discounted” packages that combine access to offices and wet labs — something in short supply in the so-called “golden triangle” of the UK’s university cities of London, Cambridge and Oxford in the south-east.

The Chevron Studio programme, meanwhile, was launched in 2021 specifically to match intrapreneurs at Chevron with ideas coming out of universities and labs.

“The universities and national labs are our technology partners, and we reach out to the intrapreneurs through our networks and offer them the IP,” says Chevron’s Phanse. If the intrapreneur and researcher team can create a promising startup, the Chevron programme will provide them with seed funding and support them from the lab to the incubation phase to field trials. The startups don’t become part of Chevron — the idea is to create independent startups, but Chevron does benefit from the learnings that come from the early view on breaking technologies, says Phanse.

5. Corporate partners need to be “builders” not “consumers”

One of the most helpful things a corporate partner can do is to help spinouts understand a path to commercialisation, says Chevron’s Phanse. This is one of the things the Chevron Studio programme tries to do, he says.

“If you’re successful in this incubation phase, you can do a scale-up phase, and we are there with you. If you do that, we will be there to do a field trial with you. And that’s something that startups really are looking forward to, so [we] try and make that pathway visible to them, giving them the right system.”

In fact, corporates who get involved in university spinouts should be prepared to bring value from the start. Don’t expect a working product, know that the road to get there will be long, and that corporate partners need to get their hands dirty helping spinouts get there, says Vanhoutte.

“You should be fully aware as a corporate on where you expect to bring value during that process,” he says. ”Be a builder and not a consumer.”

6. Make sure you have intelligent capital

Having “intelligent” capital in the university ecosystem is essential for increasing the number of spinouts coming out of a university. Oxford was a good example of this. Before Oxford Science Enterprises (OSE), the university’s early-stage venture capital arm, was founded, the university was spinning out just a couple of companies a year. Within nine months of OSE being launched the university was spinning out 20 companies,” noted moderator Thierry Heles.

Corporate venture investors, too can be intelligent capital, as their strategic focus can mean they have more patience for long-term investments than financial VCs, says Mindforge’s Smith. But universities may also have to set up their own patient capital vehicles to help bridge the gap.

Watch the full webinar here:

This webinar was part of our The Next Wave series. Previous webinar episodes can be viewed here.

The next webinar in this series will be: How to invest as generative AI startups spread to every industry on August 9, 2023. Sign up here to secure your place.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).