Oil and gas companies' profits have risen more than five-fold in the last two years. But investment activities are increasing more slowly.

Oil and gas companies have seen their pre-tax earnings increase five-fold over the last two years, but their spending on corporate investments have not gone up nearly as fast. The number of deals being done has doubled but, apart from a blip in the first quarter of this year, the amounts being invested are similar to two years ago.

We would have expected corporate investing commitments to show more of an increase, given the urgency of tackling the climate emergency and the fact that energy companies have some of the fattest corporate wallets at the moment. But while energy companies have invested in the $150m series C completed by robotics factory robotics producer and $250m series G round raised by fusion power developer TAE Technologies and the energy sector has remained the most buoyant sector amid a general market pullback, there has been no big rise in investment activity in line with growing profits.

Oil and gas profits

It is worth a quick recap — back in the second quarter of 2020, as the covid pandemic took hold, the West Texas Intermediate benchmark price for oil went into negative territory, due to a technicality of the futures contracts. Even in November 2020 it was still at around $37 -$40 a barrel. In the second quarter of 2022, fuelled by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the price had reached $120 per barrel. It has eased a little since then to fluctuate between $75 and $100 a barrel, discounting a looming recession in the Western world which may hold back demand.

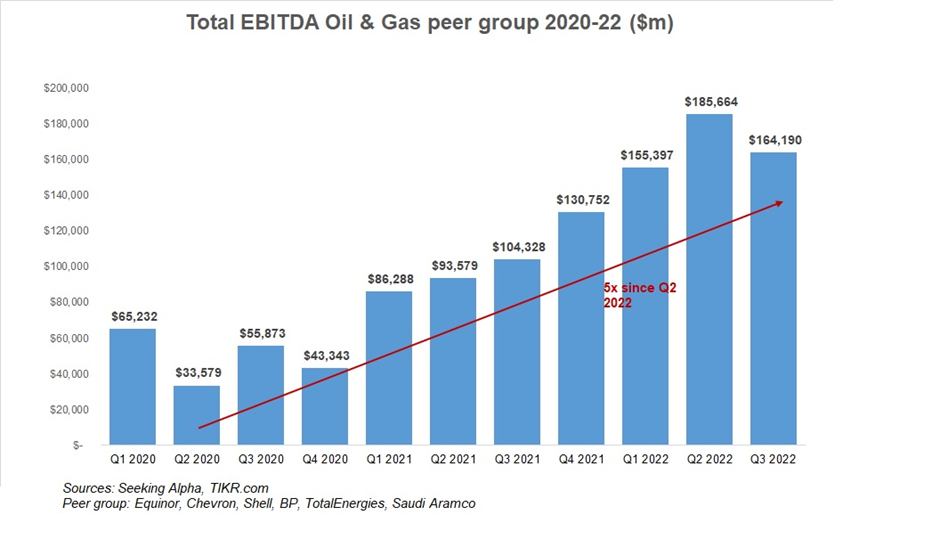

Exactly how that has translated into profits for oil and gas producers is a little nuanced, and it is possible for accounting minutiae to obscure these. But we’ve taken EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) as a measure and aggregate it for such large energy companies involved in corporate venturing – Shell, Chevron, BP, Equinor, Saudi Aramco and TotalEnergies.

While EBITDA is not a standardised accounting measure, it is widely used in the world of finance and investing as a more or less credible proxy for the company’s free cash flows. Some facetiously consider the acronym to stand for “earnings before I tricked the dumb auditor.”

As the chart here illustrates profits, quarterly EBITDA have grown several-fold since the second quarter of 2020 and the outbreak of the covid-19 pandemic. In the dismal Q2 2020, they constituted an estimated $33.57bn, while in Q2 this year they were $185.66bn – that is more than 5.5 times more. In the last quarter, Q3 2022, the aggregate estimated EBIDA amounted to $164.19bn.

These are, by any measure, significant increases in quarterly profitability figures. But has there been a corresponding increase in corporate venturing? Before we dive into that question further, it is also worth noting, in all fairness, that there have been governments levying “windfall profit taxes” on oil and gas companies.

Windfall taxes?

The argument is that an increased tax burden for a cyclical industry as oil and gas would eat up capital which could be otherwise invested in capital expenditure, refining capacity and innovation to ultimately drive prices of oil, natural gas as well as refined products. The same argument could be made around reducing extra funds for VC investing respectively.

While it is true that many governments, particularly in Europe, have imposed such levies to grapple with the ongoing energy crisis and rising costs of electricity, these measures have not been uniform in rates or structure. According to data cited by the Tax Foundation, some countries like Greece and Romania have imposed rates as high as 90% and 80% over a baseline period, others like Spain just 1.2% over sales of domestic power utilities over €1bn. Other countries have failed to implement such tax schemes altogether. According to Reuters, the windfall tax proposed by the Biden Administration in US seems unlikely to go through Congress at the moment.

Where a levy is announced, it is also worth reading the fine print. The UK, for example, imposed a 25% tax that applies to profits made from extracting UK oil and gas, excluding activities such as refining oil and selling petrol. It also gives companies 91p of every £1 invested in fossil fuel extraction in the UK.

According to the BBC, Shell, for example, stated it wasn’t expecting to pay any windfall tax at all this year but it expected to pay some in 2023. Windfall taxes, are in short, variable, but not nearly as onerous, in many cases, as headlines would suggest.

Corporate venturing likely on standby

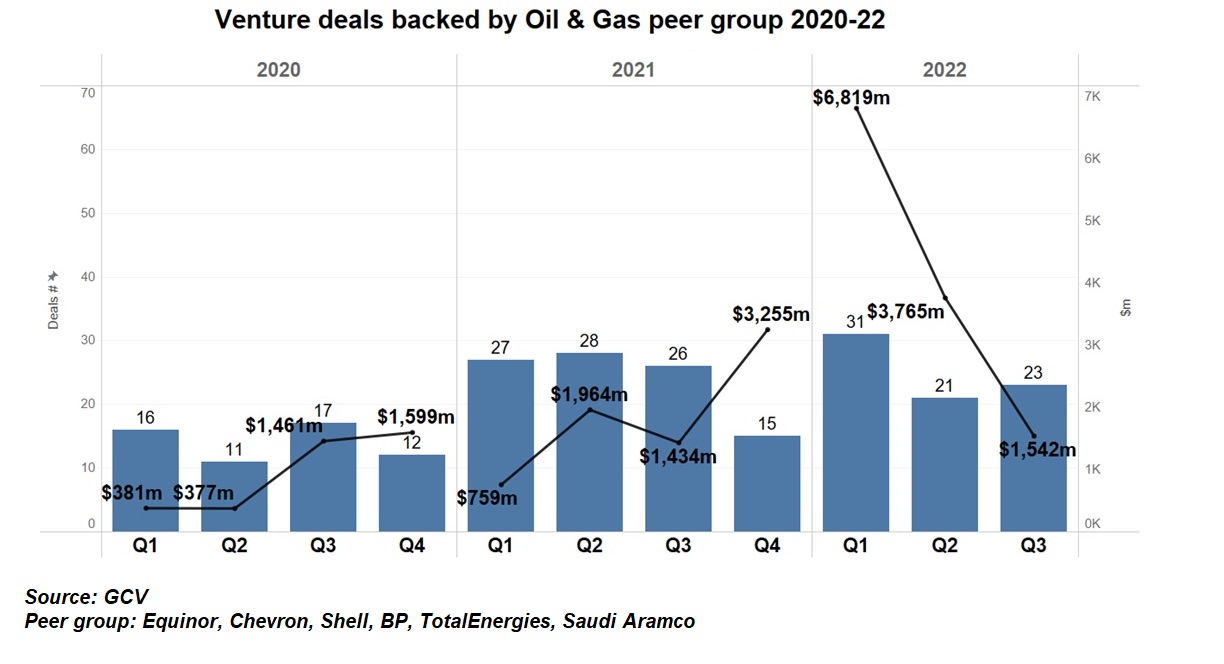

Oil and gas companies should, then have increased budgets for venturing. And it is true that, in the second quarter of this year, the same peer group of oil and gas companies did almost twice the number of deals (21) as they did in the same quarter of 2020 (11). But that is a smaller increase than the 5-fold growth of ebitda.

In total dollar terms the picture is mixed. The first quarter of this year saw total deal values backed by the oil and gas group reach a high of $6.82bn (the $775m Silicon Ranch deal backed by Shell, among other investors, was one of the deals in that quarter). That is nearly 18 times the total deal value ($381m) back in Q1 of 2020. The overall bull market is likely to have bolstered valuations in the first quarter.

But, looking at the chart overall, this year’s first quarter number looks like an outlier, and the overall trend has been for deal values to bounce around the $1.5bn level across most of the last few quarters.

One investment professional in the oil and gas industry — who wished to remain anonymous — told us that it may be a case of deliberately holding back firepower. “The limiting factor for us has never been the capital,” he said. “For established CVCs, consistency is more important. Instead of feast or famine, executing the fund strategy is key. Overall [being in a] syndicate, driven by smart money is key. We see movement in the right direction for the core oil and gas [businesses], mostly by private equity, which should help to fuel startups in this area.”

But we may be about to see a little more capital being deployed by the oil companies as the investment pullback continues. “It is good to get dumb and plentiful money out of the system,“ he said. As well as investing in core oil and gas applications, energy companies also invest in digital tech and cleantech. The valuations of digital companies, in particularly, have been “slowing down in a good way,” he says.

“For future energy, any overall slowdown in the general climate change environment is actually productive – get[ting] the valuation of the pre-revenue companies back to reality. Funding is still there but more aligned with fundamentals.”

So while we haven’t seen investment by the oil majors rise at anything like a pace to match their rising profits, it may well be that an increase is coming, with energy investors waiting to opportunistically strike as the market cools just a little more.