For corporate venturers, is it better to invest directly from a corporation’s balance sheet or from a stand-alone fund?

Investing directly from a corporation’s balance sheet is plagued by many shortcomings when compared with investing from a standalone fund in corporate venturing. It is in times of economic distress or of C-suite turnover that corporate venture capital (CVC) professionals become most aware of its disadvantages.

Is the question about which approach is better such a no-brainer as it might seem? While keen to point out the upside of having a separate fund, heads of corporate venture units know the downsides of the other approach but have been very creative in trying to find solutions for it.

“Honestly, I would strongly prefer to be investing out of a fund. I make it work and we are accomplishing great things – but I would say that we are making incredible investments in spite of being [investors] off balance sheet not because of it,” said a CVC unit head who wishes to remain anonymous. This statement sums up how many CVC heads feel about the matter, especially at a time when leaving another tech boom era behind us and entering the unknown bear market territory.

Corporate venturers who are fortunate to have such stand-alone fund setups agree. Dong-Su Kim, the managing director of LG Technology Ventures, part of electronics conglomerate LG, listed the advantages: “We do manage funds as a separate entity and although we work closely with our affiliates, we have quite a bit of autonomy.

“I believe that having a separate fund is advantageous in many ways, including better financial performance, attracting and retaining talent, quicker investment decision, long-term continuity, and accountability.”

Similarly, Aleksandr Kamenetskiy, chief operating officer of Munich Re Ventures, the corporate venturing arm of insurance company Munich Re, added: “At Munich Re Ventures, we invest out of four standard closed-end 10-year funds, all with sector-driven investment mandates and single LPs from the Munich Re Group umbrella.

“Investing out of separate funds allows for a professionalised approach to portfolio construction and reserve strategy, helping to optimise financial returns. We also find that investing from a fund structure tees you up to have more independence in decision-making and creates a discipline and standardisation that the rest of the industry is familiar with.”

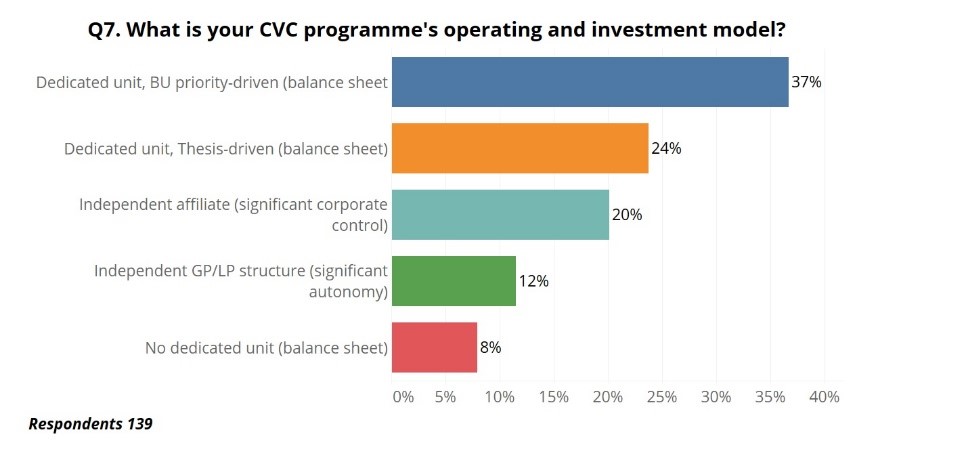

What could be the contrarian view, though? After all, if having a separate fund is a better approach, then why are such setups less common among corporate investors? According to our last annual survey, the majority of corporate venture investors (69%) operate funds directly from the corporate balance sheet, whether with or without a dedicated unit.

It might have been the unwillingness of corporations to adopt a different kind of setup for their CVC arms. But there must be something more to it than the mere reluctance of C-suite executives to put a large amount of money into a separate fund.

A case in point is the oldest surviving CVC unit, Johnson and Johnson Development Corporation (JJDC), established in 1973, and it invests from the corporate balance sheet.

According to Marian Nakada, vice-president of venture investments, the unit sees this approach as key to its success and alignment with the corporate mothership: “JJDC’s mission is to invest in companies that have the promise to develop medications and devices that Johnson & Johnson could onboard if they are appropriately derisked.

“We invest from the corporate balance sheet and our investing team is part of a corporate function within the Johnson & Johnson Family of Companies. This structure keeps us closely aligned with our R&D stakeholders and allows us to pursue our strategic mandate as our primary goal.”

She also spoke of the type of returns this setup provides: “Our model provides ‘returns‘ not just to Johnson & Johnson but also, we believe, to the entrepreneurs in these portfolio companies who benefit from long-term support at all stages of their discovery, clinical development, regulatory review, manufacturing and commercialisation, beyond the capital we invest.“

To Matthew Jones, managing director for North America at Solvay Ventures, which invests on behalf of chemicals group Solvay, it is more about clarity on the financial and strategic goals of the unit: “The benefit of a sole LP fund, regardless of if it is a balance sheet fund or a stand-alone entity, is the clarity in defining the financial and strategic goals of the fund.”

Jones highlights establishing internal connections within the corporation is the number one advantage of investing from an internal unit funded by the corporate balance sheet and contrasts that with issues endemic to traditional VC funds: ”Having worked at a VC fund with multiple corporate LPs, it was a significant challenge to align the interests of the GP, LPs and the startup companies themselves.

“For a single LP fund, the benefits of being a balance sheet fund is the internal access and credibility we have solely due to the fact that we are employees at the same company. For the startup or portfolio company, this means unfiltered access to our internal resources and ultimately better relationships.”

Jones does not deny the drawbacks of balance sheet investing but takes a different perspective, stating that CVC units may have already become a must-have in a corporation’s innovation toolkit: ”The historic ‘con’ to a balance sheet investing was the potential elimination of the CVC activity with a change in corporate leadership – it is easier to close down a balance sheet fund than a stand-alone entity.

“However, over the last 20 years, I have seen CVC activities move from a novelty to a core part of most corporations’ innovation strategies. So, I no longer see this as a major issue for either the investment professional or their portfolio companies.”

Mario Augusto Maia, head of investment at Novozymes, raises a valid point regarding corporate venture investing that both approaches may sometimes be appropriate: “Tactical investments, considered on a case-by-case basis, can provide the corporate with the optionality to make business-specific investments which may not necessarily be part of a defined broader long term investment strategy, but nevertheless can help enhance or create value for a given division or function. It can be complementary to a capital-committed investment fund structure.”

One of the other disadvantages of investing from a corporate balance sheet has to do with speed of decision making. However, there are existing CVCs with structures that tackle this problem successfully.

Leick Crispin, the head of Germany-based utility company EnBW’s venturing arm, explains: “EnBW New Ventures puts the success of our founders and startups first. To achieve this, we have built a CVC structure with fast transaction decisions and we can tap into a contractually agreed corporate capital commitment.

“We invest [using a] theme-based [approach] from our own balance sheet. We, therefore, do not have to go through corporate committees and processes and do not have corporate budget interference. This setup is an important piece for our success.“

And EnBW New Ventures is not the only corporate venturing unit that has solved problems creatively. In the first one of the case studies outlined here, we look at how JetBlue Ventures has dealt with the uncertainty of investing from the balance sheet of an airline – a cyclical business that was affected by the pandemic. In the other case study, we examine the evolution of HorizonX, which started out as the venturing unit of aircraft and defence manufacturer Boeing, investing from its balance sheet, and has now evolved into an independent investment entity focused on the aerospace industry.

JetBlue Technology Ventures – balance sheet investing that works

Amy Burr, president at JetBlue Technology Ventures (JTV), the corporate venture arm of JetBlue Airways, explains how JTV invests directly from the corporate mothership’s balance sheet through a specific arrangement: “We do invest entirely from the corporate balance sheet with a bucket of money earmarked for us, which we update and decide on together with the senior leadership at JetBlue.” The venturing unit, however, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of JetBlue’s, boasting its own charter.

There is an investment committee that decides on investments sized above a certain threshold, while the president of the unit has discretion over any deal sized below that threshold. The committee is composed of JetBlue’s general counsel, CFO, the president of travel products, the chief digital and technology officer as well as an external CVC leader who brings the perspective of a venture investor.

The decision on the amount of money designated for the unit is made every year but discussed actively as well over a larger period of time: “Several years ago, our board talked about the next few years and made decisions about the future of our venturing unit. We have plenty of money to invest and we would expect to have more or less the same amount to deploy in the coming years. The amount has grown over the past six years and we expect it to grow over the next few as well.”

It is the JetBlue‘s president of travel products, CFO and the general counsel who jointly decide on the amount of money to be earmarked for JTV but it is the CFO giving it the ultimate blessing.

The expectation of having the capital to invest has much to do with capital requirements in venture investing: “We have invested in 39 companies so far over the past six years, along with 24 follow-ons. We are strongly committed to doing follow-ons, as long as the portfolio companies are strategically important to us and viable.

“A lot of companies in our portfolio have already matured and are raising a later-stage round, where the amount required to get our pro-rata just gets bigger. And we just want to make sure we invest the right amount.” This is true even in a time when valuations are undergoing corrections and there are more down rounds than usual.

What are the pros and cons of this setup? Burr stated that it has worked well for JetBlue’s venturing arm but it has some potential downside: “It is a model that works for us. There is, however, always the risk of an economic downturn and unless you have very strong support at the senior executive level in the mothership, which we do, it may mean seeing your funding for deals reduced or cut entirely.

“In our case, we are confident in support from the c-suite and we have actually survived board leadership changes already.”

What is Burr’s advice to up-and-coming CVCs with little to no track record? Simply start by using a different model: “Ideally try to secure that capital and place it in a separate fund controlled by the CVC alone. In a case of an economic downturn, a pandemic or leadership change, you do not have to worry about it. It is not our model and how we have done it but I can definitely see that it is less risky for a unit that is just starting in an environment like the present one.”

Do investment track records and exits matter to the mothership when deciding how much funds to assign to JTV? Burr reveals with sincerity: “I am not sure how the exits we have had will impact the amount of money we are going to get. The money from an exit does not go directly back to JTV but to JetBlue, so it will be interesting to see how it plays out longer term.

“However, I think it puts us in a more secure and comfortable position with our C-suite because, at the end of the day, we are investors and it is always great to have something to show for it.”

Burr also shares her thoughts on alternative models of corporate venturing arms raising capital from external limited partners: “Another question to think about for newcomers is: do you take money from outside the parent company? This kind of model has not gained as much traction and is not as common, at least to date.

“I think it is largely because CVCs are created by their corporate owners mostly with strategic goals in mind. However, for some corporations that may be a good way to further de-risk their venturing operations. It is a combination of wanting to be involved but not being willing to risk very much.”

Finally, Burr also notes that there is a carried interest compensation arrangement at JTV – something which is relatively rare among CVCs in general and especially units investing from the corporate balance sheet. Under the arrangement, whenever JTV strikes an exit, the cost of the investment is returned to JetBlue, and if there is profit, it gets shared between JetBlue and JTV. JTV then shares it across the team. “It is one of the best ways to attract and retain top investment talent,” says Burr.

HorizonX – evolving after the kiss of death

HorizonX Ventures was founded in 2017 as the dedicated CVC arm of Boeing. Subsequently, the unit, along with its portfolio, was spun out to AE Industrial Partners (AEI) in a strategic partnership with Boeing in August 2021. Today, it is dubbed AEI HorizonX and forms the venture capital platform for AEI.

Brian Schettler, partner at AEI and head of AEI HorizonX, created the venture unit inside of Boeing and has led these activities since its first existence. He reveals the spinout was a deliberate decision in light of future macroeconomic expectations of a world with rising cost of capital: “The rationale behind it was an intentional evolution of the structure.

“This structure allows us to become more creative and continue investing in new technologies in a cash-constrained world, while supporting our portfolio companies maturation and commercialisation of their technology to impact the aerospace and defence markets more broadly.”

Boeing has continued to show support for this outsourced CVC model through their commitment of $50m as an anchor investor in AEI HorizonX’s second fund, announced in July 2022, almost one year after the spinout.

He also clarifies that the decision to spin out was made in order to preserve a fully functioning venture unit of a corporation faced with many strong headwinds: “When you are 100% invested and capitalised by the mothership, you are unfortunately caught in the cyclicality of budget and balance sheet performance.

“The last three years were some of the most challenging in Boeing’s 105-year history. So, rather than just accepting a scenario that could see HorizonX being shut down, paused or hibernated, it seemed much more beneficial to the existing portfolio to leverage the expertise of a combined team – the team we had created in partnership with AEI.

“In fact, now we can accelerate what we were doing, make more investments, raise more funds and keep our focus on aerospace tech innovation and adoption.”

Laurence Vigeant-Langlois, managing director at AEI, provides the AEI perspective on the symbiosis with HorizonX: “We were a private equity firm with a significant amount of capital deployed and involved in buyout activities.

“About two and half years ago, we decided to get into venture capital and did several investments from our portfolio companies’ balance sheets and our partners’ capital. We approached Boeing with the possibility of really accelerating our entry into venture capital for various reasons.

“It gave us visibility and opportunity to invest earlier in innovative businesses doing ground-breaking work in technology sectors within our target markets. It gave us access to early-stage companies with lower valuations as well. So, the partnership helped us accelerate what we were doing by bringing into the fold a fantastic team of seasoned VC professionals and a portfolio of pre-existing investments that may be primed to scale up and grow.”

In its present setup, AEI HorizonX invests and runs as a separate traditional venture fund, but that was not always the case. While it was still part of Boeing, the unit was investing from the corporation’s balance sheet and being part of such a corporation comes along with certain benefits, according to Schettler.

“When you are inside of Boeing and investing from the balance sheet, you are viewed as what you are – a member of the Boeing team and that connects you to other people in the company,“ Schettler continued. “You are perceived by some as ‘safer’ as opposed to someone from outside the company. That, at the end of the day, was probably the biggest advantage in transitioning outside technology into a large corporation. It was just all under one roof.”

However, he states investing as an independent fund subsequently may have outweighed the advantages of being an insider at the corporate mothership, especially when it comes to perception: “The benefits of being outside now are much greater with the overall setup. Now, we can tell not only startups but also other potential investors that we are a dedicated VC fund with a fiduciary duty to our investors.

“In contrast, when you are inside a big company like Boeing, some may view you with certain scepticism regarding your true intentions. Is what you are doing just for Boeing’s interest or are you looking for the industry’s best outcome or the best outcome for the startups?”

He also added that the new fund setup has helped to improve not only communication but also deal flow and execution speed: “We were able to minimise such scepticism dramatically by being an independent fund. The types of deals we can now get into, and the deal flow we have access to have improved, because – quite frankly – some people do not want to talk to you if they are developing a solution that is competitive to Boeing.

“We have gained exposure to higher-quality deal flow. We are also able to make decisions and execute in a true fund setup, as opposed to a heavily hierarchical and bureaucratic one that you tend to find in big companies. The speed of executing deals is much faster as a result and we have expanded our network through AEI and its investment professionals.”

However, he also pointed out that, despite being an independent fund, AEI HorizonX can still leverage its connections to Boeing to add value to portfolio companies. The fund does not reveal all of its current LPs but Schettler points out that Boeing is one of them: “Boeing is an anchor investor in both our current and second fund. They solidified that as part of the spinout, as it was not something they were abandoning and they wanted to stay as an anchor LP investor. They envision continuing to partner and invest in us in the future as well. It is an enduring partnership.”

Schettler also speaks straightforwardly about the disadvantages of corporate balance sheet investing: “The obvious weakness of balance sheet investing is that it is unpredictable. You are not a dedicated fund and you do not have a set amount or a commitment.

“When you run a venture programme, you like to know how much money you will have and that would impact the number of deals you make. It shapes the allocations you have in each company and how much reserve you keep for follow-on investments. With balance sheet investing, the best you can do is just react to the CFO’s guidelines.

“You may have $100m this year but it may not be $100m next year. It could be $20m and it is a much more difficult environment. All of that triggers serious concerns among the startups and among other investors in the syndicate who depend on follow-on investment.”

Vigeant-Langlois, who serves on the investment committee of AEI HorizonX, concurs with the better perception of a separate, dedicated fund: “I think the advantage of the formalisation of a fund has to do with the longer-term future of how the fund is seen and recognised as a fully committed co-investor.”

She also believes the benefits go beyond that: “There is the optimisation in terms of what deals we make – should we invest more or less in company A, B or C depending on the outcomes we are looking for in terms of ROI or other aspects of our fiduciary obligations.

“Optimising our strategy makes us more committed and we do not face the constraints of a ‘make or buy’ decision that a strategic investor might have.”

Another clear advantage of running a dedicated fund almost invariably has to do with compensation structure, as CVCs tend to not have carried interest compensation, which traditional venture and private equity firms do.

Schettler said how having skin in the game has motivated the AEI HorizonX team members differently. “When you are inside a big company, generally you tend to have preset compensation structures. The compensation of the leader of the unit, as an executive, is certainly comfortable, even if not entirely up to VC norms.

“Where you really run into trouble is in regard to long-term talent retention and attraction at the junior level. You cannot pay them an executive-like salary inside a large corporation like you would find at a VC firm.

“At some point, they start seeing more value elsewhere and start moving on. So, our transition to AEI was very beneficial in that respect. It is much more motivating for the team to try to make the best decision possible; not just an emotional one but in terms of a high-quality investment decision when part of their own personal capital is on the line. I have noticed that in the quality of the discussion and debate we have when selecting a company to invest in.”

He contrasts that with investing from within CVC inside a corporate structure. “You need to have that investor orientation as the fundamental driver. When you are in a big corporation, you are not penalised if you make a bad investment, but you are not really rewarded if you make a great investment either. Motivation is totally different.”

What are Schettler’s tips for upcoming CVCs and those planning to assemble a corporate venture program? He recommends trying to blend the best of both worlds by starting from the inside and then spinning out: “I am biased but I think the approach we took is just about the best way if a new company should think about a CVC programme.

“It would be very hard for a big company to embrace venture capital if it starts externally. You have not built up the internal advocacy, support and network inside the company, and you lack the awareness of the key touchpoint strategies and needs.

“Having something internal first to lay the groundwork for the culture, relationships and value proposition work nicely. Longer term, however, it may not be sustainable for the company’s best use of its balance sheet. You can have this creative structure where you free up a big budget consideration while still maintaining some exposure and allowing other investors to join.

“I think that is having the best of both worlds. But you have to leave something behind to provide the strategic linkage. Currently, there is a dedicated team within Boeing that is trying to drive the adoption of technologies we invest in and that makes all the difference.

“For them, it means extracting better value out of the visibility that our VC investments provide them. For us, it enables us as independent investors to be more successful in getting adoption from big companies, and in turn to create better value for the startups we partner with and invest in.”

Vigeant-Langlois, in turn, views the AEI HorizonX model as a viable alternative for corporations that need to have visibility into the innovation scene but may be constrained in terms of resources. “You cannot predict disruption outside your business, and are especially vulnerable to the tunnel effect when they are in a potential downturn,“ she said.

“Ensuring visibility to the world of innovation can be partially achieved via venture capital with the right structure; we think our model provides a balanced approach to ensure that visibility is in order to enable strategic players to get such visibility and also to unlock financial, technological and reputational benefits.”

Schettler also stresses the importance of maintaining such visibility. “If you just turn into a selective participant in the venture space and you are only looking at it during the good times and go quiet during the downtimes, that is probably when you would get disrupted,” he added.

“That is when you would have some entrepreneurs surviving and beating the odds to take out the incumbent. So, this model gives you the flexibility to be consistent in the innovation space, irrespective of the corporate’s financial situation.”