Recent technological breakthroughs have piqued investor interest in the sector. But just how close are we to making quantum computers useful?

This week IBM Quantum, a division of the US computer manufacturer, announced what some see as a watershed moment: its 127-qubit Eagle quantum processor outperformed a regular supercomputer on a complex calculation.

It is seen as a big deal because although quantum computers hold the promise of performing complicated computations in a fraction of the time of conventional supercomputers, machines that can reliably provide such an advantage have been slow to arrive. The quantum computers available today are “noisy” and “error-prone”, according to IBM’s own description of today’s quantum computers in a blog on this week’s breakthrough.

But is the IBM announcement a sign that we are close to developing computers that can solve the world’s most pressing problems in areas such as drug development and materials science?

Global Corporate Venturing this week held a webinar – Quantum Computing: How to invest in the next big opportunities – fortuitously on the same day as the IBM announcement.

Webinar participants consisted of Stefan Elrington, global lead for startups at IBM Quantum; Tobias Grab, co-founder and chief strategy officer of Kipu Quantum, a German startup; Markus Solibieda, managing director of BASF Venture Capital; and Christophe Jurczak, founder and managing partner of Quantonation, an early-stage VC fund.

Elrington described the IBM experiment, which pitted its quantum processor against a conventional supercomputer with the result that the classical computer couldn’t keep up with the quantum version on increasingly complex calculations, as evidence of the industry “reaching a new era of computing”.

But he also said that the company still needs to show quantum advantage – industry speak for proof that quantum computers can consistently do computations better than classical computers. “For the time being, you can rest assured quantum advantage is still something that hasn’t been reached, but we’re getting there,” said Elrington.

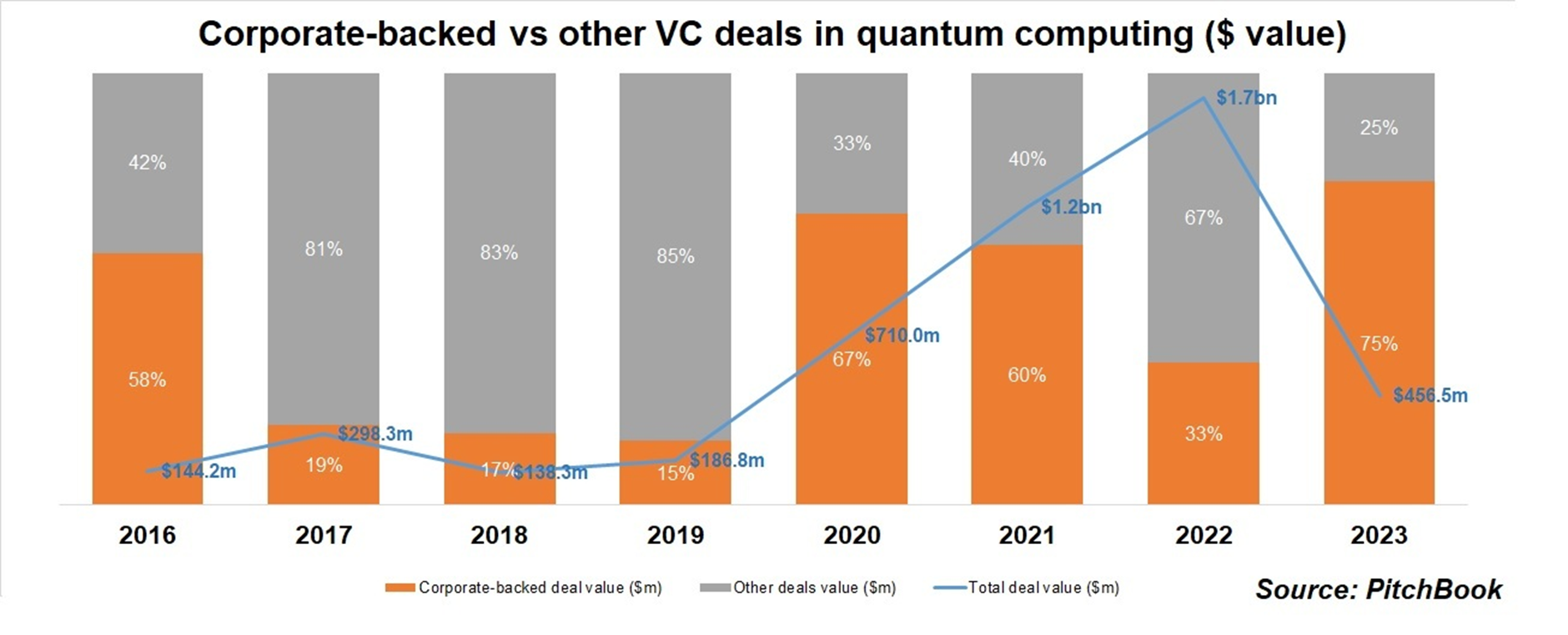

Investor interest in the sector has been on the rise, although this year the value of deals has fallen amid the high interest rate environment. Corporates represent a large percentage of investment in startups.

Recent sizeable deals include the $24m series A financing of quantum service provider Strangeworks by Hitachi, Raytheon and IBM in March. This followed a $109m raise earlier in the year for quantum processor developer Pasqual, backed by Saudi Aramco, Eni, Robert Bosch Venture Capital and Porsche.

Hardware developments slow, software faster

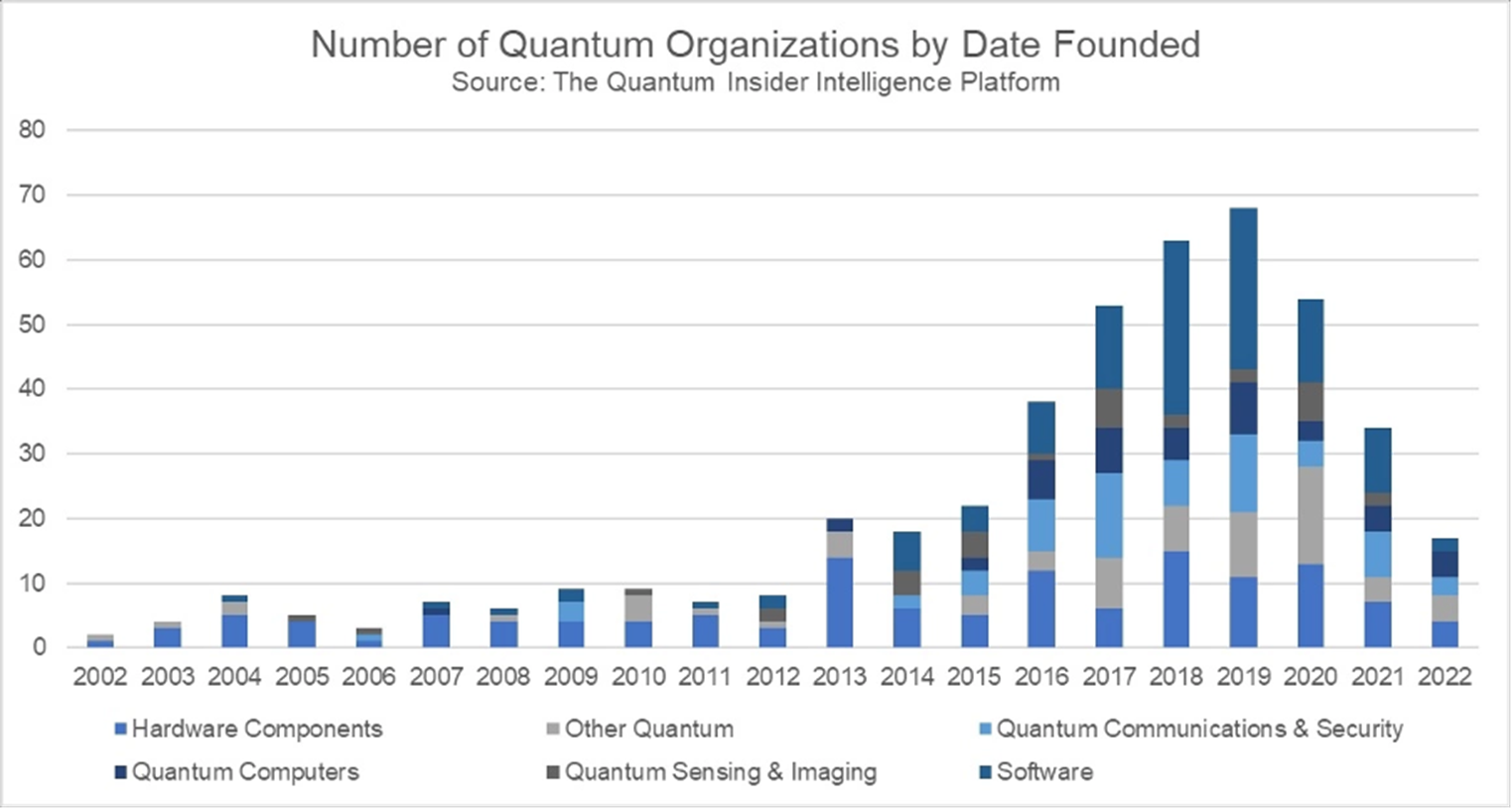

Despite growing investor interest, some are disappointed that quantum computing hardware has not made the kind of progress seen in the software side of the sector. Expectations were high that there would be computers today with thousands of qubits – the basic building block of quantum computing – points out Solibieda, of BASF Venture Capital. The corporate VC arm of the German chemical manufacturer first invested in a quantum computing startup in 2018. “Expectations at that time, certainly in terms of hardware, were that we would be further down the road today,” he says.

Some say there needs to be thousands more qubits in quantum computers – even a million and more – for them to work properly.

Progress in software has been faster. Kipu Quantum is working on a method of compressing algorithms to shorten the number of steps needed for calculations. Its technology runs on IBM machines. It recently entered a partnership with quantum startup Pasqal. Co-founder Grab sees applications for the technology in areas such as materials science, drug discovery and artificial intelligence. The startup was even approached by an investment bank that was interested in using quantum computing for financial solutions.

Emerging use cases

The chemicals industry is one sector where quantum computing could make strides. BASF has looked at quantum computing to help it optimise the logistics of running its large chemical plant in Ludwigshafen, Germany. It has also experimented with using the technology to price commodities used in chemicals manufacturing.

Carmakers and auto OEMs including Volkswagen and BMW are interested in using quantum computers to run fleets of autonomous vehicles and develop new electric car batteries.

And some say generative AI could be taken to a new dimension with the help of quantum computing. Jurczak, of VC fund Quantonation, says he has seen investor interest in quantum machine learning, but added its application is less clear for generative AI. “Quantum machine learning is real and will happen and will have an impact,” says Jurczak.

The webinar participants were careful to emphasise the importance of not overhyping quantum computing’s capability, given the limitations of the today’s technology. “We need to talk the truth, basically, and not overpromise what’s possible,” says Grab.

In the near term, quantum computers could be used more effectively for doing small sections of computations as part of a bigger system. In this way, businesses do not have to wait decades for an all-singing, all-dancing quantum computer. Jurczak envisions the technology employed as co-processors solving sections of a larger process.

“For me, the quantum processor will be solving a small problem at first in the big workflow, and progressively take more and more applications and add more and more impact, but it’s not going to change everything from one day to the other,” says Jurczak.

IBM has set out a roadmap for scaling its quantum computing model to 10,000 and more qubits. The company is also seeking to reduce error rates and increase speed. “And so far, it’s been working out,” says Elrington. “We have really large numbers of qubits available to our clients today. We’ll keep pushing on that as well as the other two parts of the equation that makes performance.”

Listen to the full webinar here: