Legal technology funding has boomed in the wake of ChatGPT, and startups – and law firms – that don't use artificial intelligence are going to be left behind.

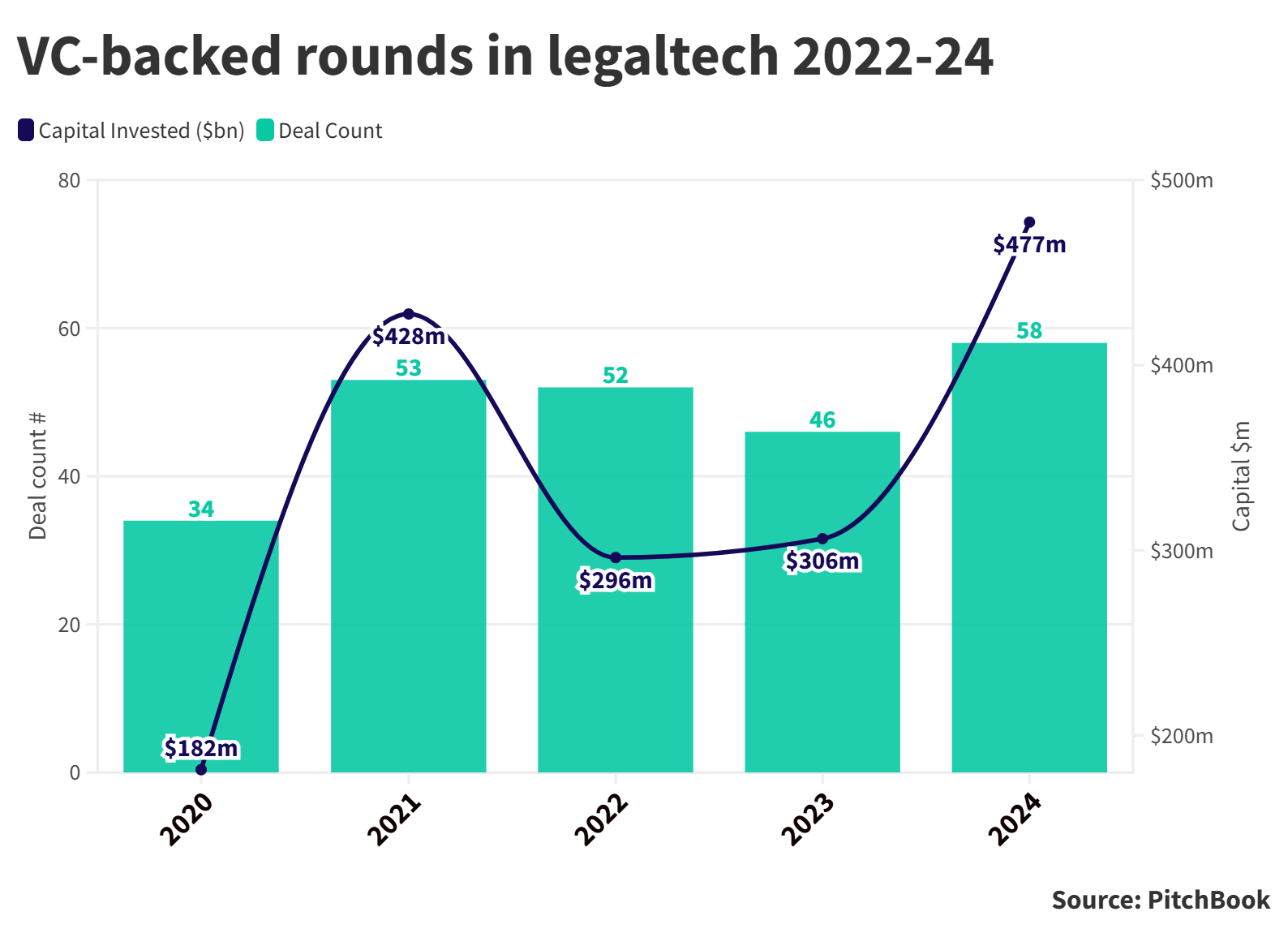

Legal technology has been one of the biggest recipients of the artificial intelligence startup boom that began last year, raising investment in legal tech startups to a record high in 2024.

Investors say AI-based legal tech has the potential to substantially shift the way law firms work and charge, especially as the technology moves from simply automating back office functions to carrying out more of the actual provision of legal services.

“The rush we saw in the first six to 12 months was around contract drafting and using AI to do certain things like negotiations and redlining (correcting documents) back and forth,” says Shubham Datta, who runs legal software producer Clio’s corporate venture capital arm.

“What I’m really curious about, and what I’m really leaning into are things that really change the workflow, or that assist in the automation of certain workflows lawyers have, and using AI to power these.”

The public unveiling of ChatGPT substantially expanded expectations around what AI can do, and while the big bucks have gone into OpenAI competitors like Anthropic or Cohere, it has also precipitated investment into areas like law. The number of legaltech startups raising money had reached a new annual high by the end of October this year, as had the cumulative amount raised.

Roughly one third of information services and technology provider Thomson Reuters’ business covers the legal industry, running into billions of dollars of revenue a year, and its CVC unit has been among the investors actively exploring the use of AI in the sector.

“For us, being able to apply models and AI to our content really kind of sets us apart,” says Tamara Steffens, managing director of Thomson Reuters Ventures. “The timing is perfect for us.”

Thomson Reuters Ventures’ portfolio includes Wisedocs, the creator of a tool that uses AI to summarise medical records for injury claims, as well as Spellbook, which applies the technology to reviewing and drafting contracts. Another investment is in Priori, an online marketplace for legal professionals. The core product was launched back in 2011, but it has now added an AI tool called Scout to automate managing law firm panels and interacting with outside counsel.

“Spellbook is probably the leading legal drafting tool in the market, and I would argue now one of the best legal assistants to go along with that,” Steffens says.

“Priori is also using AI in a number of different areas. Priori gives the tool to in-house counsel and lawyers, and if you are a large tech company and you need a specialised lawyer that knows something about, say, the Port of Louisiana, then you can actually find a lawyer that understands that.”

Legal tech has also made a jump because, while very large language models work well for wide ranging creative tasks like creating copy or images, they aren’t effective in an area such as law, which relies on highly specialised knowledge and has no tolerance for the errors or “hallucinations” to which generative AI is prone. That has created a space for specialist startups, even in specific types of law, that can work with precise information and frames of reference.

“Certain horizontal solutions like Chat GPT aren’t a great use case for legal”

Shubham Datta, Clio Ventures

“It makes a lot of sense to start in particular practice areas, where you fully appreciate and understand the nuances of a particular practice area. That is why certain horizontal solutions like Chat GPT aren’t a great use case for legal,” says Datta.

“One of the problems with these larger models is that they are trying to do so many things that when you start to look at it for very specific tasks, down to figuring out what form you may need to file for an immigration situation for a very nuanced case, it may hallucinate or struggle with that use case, because it’s taking into account so many different parameters that may not be relevant.

“Whereas, if you have a specialised solution for immigration, it is much more equipped to handle that narrow scope, and to do it more effectively and more efficiently than a large language model.”

Most law firms aren’t set up to use AI – but must learn to avoid being left behind

Lawyers are the customers who will ultimately be using AI and in practice the technology’s growth depends on whether or not they take it on. Perkins Coie, a law firm with a range of tech companies as clients, occasionally invests in AI companies – it backed AI legal compliance startup SingleFile in March – and is exploring ways startups can help enhance its practice.

Ian Bagshaw, a partner at the firm, says too many firms have not created a pathway to integrating AI into their work.

He believes it is essential to not only for law firms to have a chief technology officer but to connect them to the front of the business, to make sure the technology is adopted in a way that makes sense. There are lots of partners, lots of associates and lots of know-how, but the way that expertise is arranged can make AI difficult to adopt.

“The scope for growth is huge, but the growth in value [will be] in legal service provision, not necessarily back-office simplification”

Ian Bagshaw, Perkins Coie

“Most of the products tend to be early-stage products in relation to things like diligence and document review, which is really just the start,” he says.

“The scope for growth is huge, but the growth in value [will be] in legal service provision, not necessarily back-office simplification. And the legal service provision at the moment is still very much at the low-grade, repetitive work product end. Diligence, basic contract view linked to diligence – it’s not really doing anything more than that.

“That’s why I think a lot of law firms are trumpeting their AI strategies but very few are able to implement a consistent strategy, because it’s very hard to disrupt an entire business that turns over $2bn a year when you’ve got four or five hundred frontline partners all doing the same job differently.”

But startups are beginning to make that next step. Harvey has created a cloud platform that includes an AI-based personal assistant and a rapid research tool it claims can answer complex legal questions with accurate citations. GV and OpenAI were among the investors in Harvey’s $100m series C round in March, giving it a $1.5bn valuation just two years after it was founded.

Ideally, Bagshaw says, the industry could get to the point where software is handling up to 80% of a partner’s workload, while they concentrate on emotional intelligence-based tasks like building networks and engaging with clients.

But law is also a bespoke product, he adds, with each firm operating differently and training their staff accordingly. That’s why he believes the best way forward may be in the form of white-label software products that can be built and tailored to an individual firm’s practice and methods of working.

Ultimately however, Bagshaw sees the AI revolution in law as inevitable. Once a firm has a pathway to using AI and has worked out a consistent approach to different cases – an M&A transaction versus litigation for example – it can start building a way for the software to take on more and more of that work. And that means the firms that do use the technology are going to have a competitive advantage.

“Because if clients have a choice of deciding between people on quality, they’ll pay more for higher quality,” he says. “If the quality is not a decision point in itself, they will always pay less as a rule of the road. So, it will start impacting the way in which law firms can charge. But they’re not necessarily affecting their net profit, because it will reduce the need for lots of overhead in relation to talent assets. So, it’s a big prize.”

Datta also sees that growth as a certainty, given how much computing power is increasing. And not only is it going to be a game changer in the legal industry, no startup in the sector is going to be able to move forward without AI as a key component.

Last year, I couldn’t have predicted that we would get to this point we have in the last 12 months”

Shubham Datta, Clio Ventures

“I think the momentum that we’re seeing, with the advancements in in AI is incredible. Last year, I couldn’t have predicted that we would get to this point we have in the last 12 months,” he says.

“And frankly, we’re not interested in investing in technologies that don’t have an AI angle to them. It’s like when the cloud was getting started – it would have been foolish to invest in technologies that weren’t cloud-based.

“We are taking a similar approach to looking at investments. If they don’t have a play with AI, it makes it really difficult for us to consider that as an investment, because we don’t think that anything without AI embedded will have much staying power if they don’t have a plan to incorporate that.”