The global food system is creaking — creating an impetus for global agriculture companies to invest in new solutions. Corporates took part in agtech deals worth a record $18bn last year. But are they investing fast enough?

More than a quarter of a million additional people will go hungry in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia as the war in Ukraine cuts cereal shipments. That was the sobering report in September from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

These countries are among the world’s top importers of wheat from Ukraine and Russia. Because of the war, Ukraine will sow up to 30% fewer crops this year, decreasing cereal production by 40% compared with 2021. But it is not just the war in Ukraine that has exposed vulnerabilities in the global food system. Supply chain shocks resulting from the Covid pandemic, coupled with increasing energy prices which makes fertilisers more costly and extreme droughts exacerbated by climate change are combining to worsen malnutrition on a global scale.

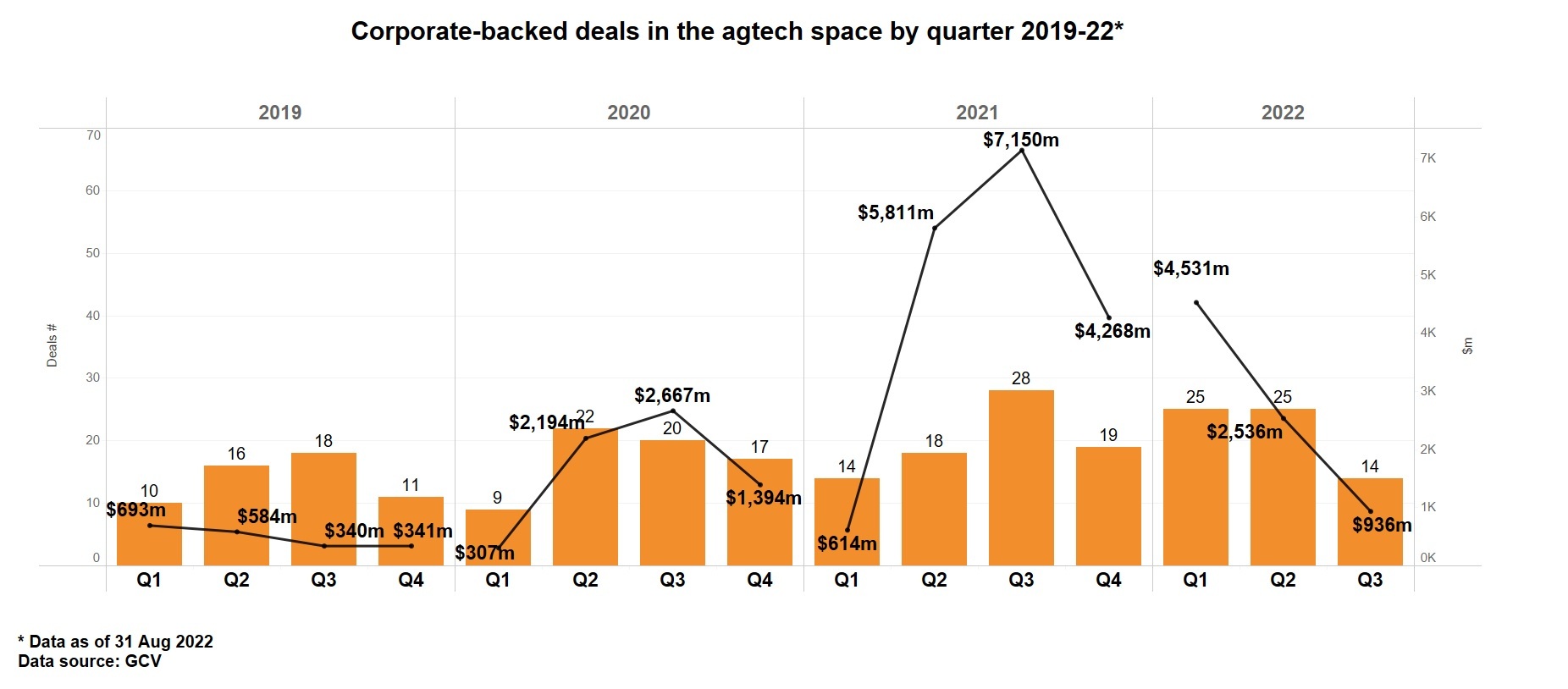

Today’s food crisis paints a compelling picture for global agricultural companies to accelerate investments in solutions to strengthen the food supply system. GCV data show that even before the war in Ukraine started in February this year, corporations had massively increased investments in the agtech sector.

Indeed, 2021 was a bumper year for investments, with corporate investors taking part in funding rounds worth nearly $18bn. The third quarter saw a peak at $7.15bn, and so far in 2022, corporate-backed agtech deals tracked by GCV have totalled around $8bn.

“There has been so much money raised in this area that the goal is to have this money deployed,” says Paimun Amini, senior director of venture investments at Leaps by Bayer, the corporate venture arm of German multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company Bayer. “We are seeing more new funds pop up in deals that we hadn’t seen over the past five to 10 years, which is great for the overall ecosystem.”

Leaps by Bayer was created in 2015 to invest in startups in healthcare as well as the food and agriculture sectors. Between its creation and the start of 2022, it has invested $1.5bn in more than 50 ventures. It plans to invest another $1.5bn over the next three years, says Amini.

“There has been so much money raised in this area that the goal is to have this money deployed.”

A big focus for the fund is investing in technologies that create alternatives to synthetic fertiliser. Nitrogen-based fertilisers, a high proportion of which are exported from Ukraine, are known for their heavy toll on the environment because they leach into lakes and streams, disrupting aquatic ecosystems. They also degrade soil by increasing nitrate levels. And the high cost of making synthetic fertiliser resulting from soaring energy prices is making it too expensive to grow food.

Leaps by Bayer has invested in several startups that produce alternatives to nitrogen-based fertiliser. One of those is Sound Agriculture, a manufacturer of a biological alternative to synthetic fertiliser for corn and soybeans, which the CVC brought into its portfolio in 2021. As a corporate venture fund, it has been able to connect its portfolio companies to partner on technologies together. In the case of Sound Agriculture, for example, it facilitated a partnership with another of its portfolio companies, Apollo Agriculture, which works with smallholder farmers in Kenya to improve access to financing, seed, fertiliser and pesticides. Sound Agriculture’s biological alternative to synthetic fertiliser will help smallholder farmers that Apollo works with use less synthetic fertiliser and avoid nitrogen run-off.

Another focus area for the fund is what Amini calls the “next wave of genetics 3.0”. This refers to biotechnology solutions that make plants more resistant to pests, diseases and drought. “Having plants that are not just able to handle bugs and weeds but the environment has always been important, but even more so given the climate effects that we have seen over the past couple of years,” says Amini.

The fund is also honing in on digital and financial technologies that improve farmers’ access to credit. Apollo Agriculture, for example, uses satellite imagery and artificial intelligence to understand weather patterns and soil conditions. This data is then used to create financing packages for farmers, so that they can afford to buy products such as seed and fertiliser.

Amini has found several overlaps between the fund’s healthcare portfolio companies and its agtech investments. As a CVC it has helped startups adapt technologies that have applications across both sectors. For instance, one of its healthcare startups, Ukko, uses immunology and machine learning to create proteins that can treat food sensitivities such as peanut and gluten allergies. “That same technology can be applied to wheat, which means wheat may eventually express naturally a version of gluten that is non-reactive for people,” he says.

Asia Pacific flags investment potential

Certain Asian countries such as India and Singapore are positioning themselves to attract agtech venture capital, and CVCs have launched investments as a result.

The Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB) injected an additional $14m into its Corporate Venture Launchpad programme in July this year to help more companies support startups in areas such as agtech and fintech.

US food conglomerate Cargill announced the launch of its first “digital business studio” in Singapore in September to finance food and agriculture startups in the Asia Pacific region. It is partnering with the Singapore Economic Development Board to develop a portfolio of at least five new startups through the studio. “With Singapore’s prominence and reputation as a vibrant agri-innovation hub, we are pleased to collaborate with EDB on this initiative,” said Ross Hamou-Jennings, chair of Asia Pacific at Cargill, in a release.

Varied approaches globally

Another CVC expanding its agtech investments is FMC Ventures, the corporate venture arm of FMC Corporation, a US agricultural sciences company. It plans to triple its agtech investments in the next three years, according to its new managing director, Mark Brooks. The fund, which was set up two years ago, has invested in six startups, one of which – BioPhero – it acquired in July.

“It is very important for FMC to learn and collaborate with early-stage companies and to be a leader in the entrepreneurial ecosystem,” says Brooks, who joined the venture fund in July from Syngenta Group Ventures, the investment division of the Chinese-owned seeds and pesticides company.

“There haven’t been that many exits in the agtech startup world compared with other sectors. But it is a rapidly growing space. Just in the past five years, the number of startup companies that are trying to solve the problems of sustainability and food security has significantly increased and so has the volume of venture capital money,” says Brooks.

The fund wants to expand its portfolio globally. Brooks points out that the challenges facing agricultural production vary wildly across the world. The US is relatively efficient in agricultural production compared with countries like Brazil, for example, where the banking infrastructure for farmers is weak and the size of farms are massive compared with other countries.

Technologies that the fund is keen to invest in include biologicals and precision agriculture – applying the right nutrients and chemicals to plants at the optimal time. Like Leaps by Bayer, it is interested in fintech solutions for farmers, particularly in emerging economies where it is hard for growers to take out loans to buy high quality agricultural products for better yields and profitability.

“Farmers are drowning in data.”

Integrating the massive amounts of farming data into systems that help inform growers when it is best to grow crops is another big investment area for the fund. “Farmers are drowning in data. There is data coming from satellites, tractors. But none of those data sources talk to each other or able to be easily integrated,” says Brooks.

Compared with other sectors like pharmaceuticals and consumer electronics, agtech is a relative newcomer to innovation. But that also makes corporate venture funds ideally placed to the help the startup ecosystem mature.

“I am really encouraged by agtech’s ability to shape the story of climate change and sustainability. The best days are to come,” says Brooks.

This article was amended to clarify that Cargill’s partnership with the Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB) to launch a digital business studio is separate from the EDB’s Corporate Venture Launchpad programme.