Stellarators are emerging as one of the most backable fusion technologies, and investors say the first pilot reactors could be working by the end of the decade.

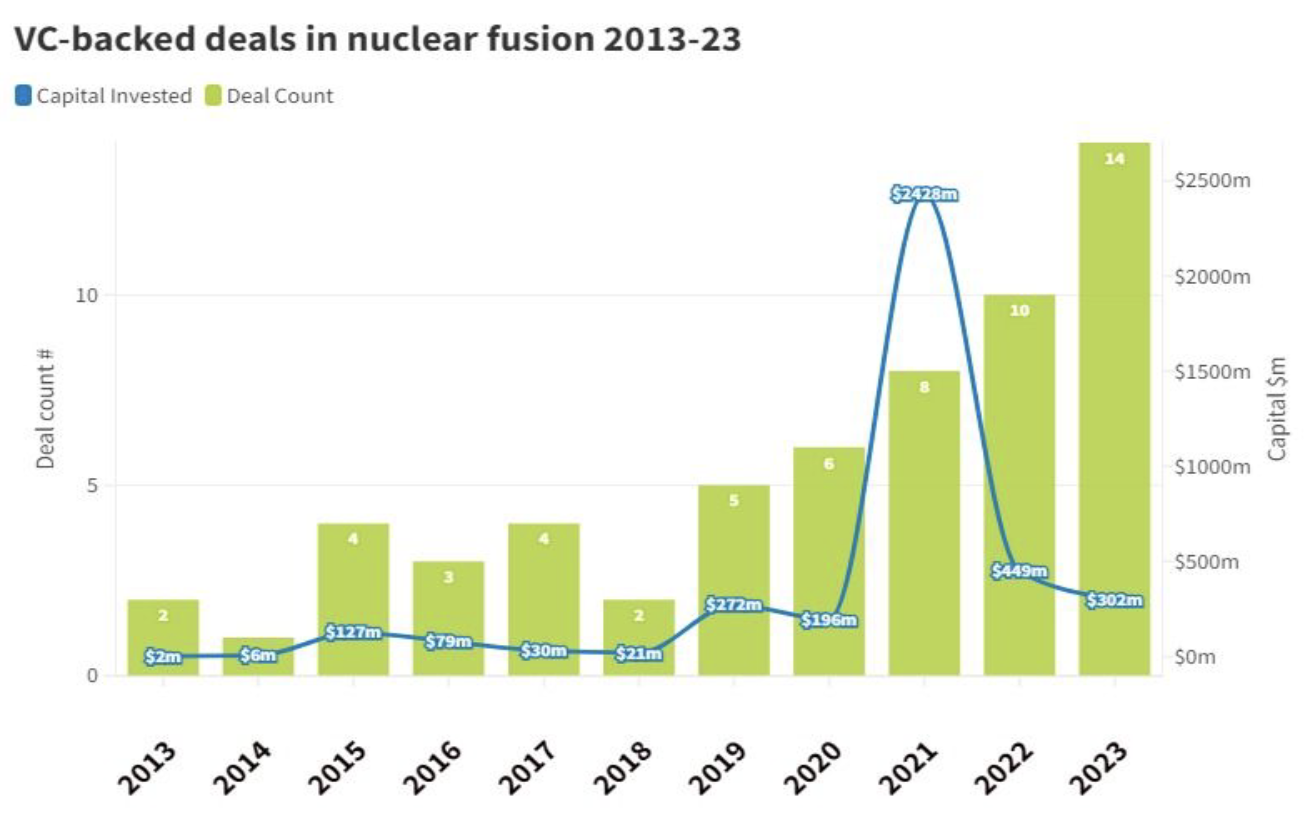

Nuclear fusion appears to have suddenly become investable. There are now 43 private fusion companies in operation and 2023 saw 14 fusion startups raise funding rounds, a record number.

Enthusiasm to invest has been fuelled by recent breakthroughs in generating energy from nuclear fusion. At the end of last year the National Ignition Factory in the US managed to produce more energy through a nuclear fusion than went in, and in March the Wendelstein 7-X stellarator at the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics in Germany achieved a record of generating 1.3 gigajoules of energy from a reaction, a big step change from previous levels.

These kinds of breakthroughs are convincing some investors that nuclear fusion is on a path to becoming a commercialisable energy source. Many are eager to get in early on what they believe will become a new megatrend, with the first payouts feasible within the timeline of a standard, 10-year venture capital fund.

Two fusion investors, Tina Tosukhowong, investment director at TDK Ventures and Wolfgang Seibold, partner and chief financial officer at Hitachi Ventures, joined the GCV webinar, Reaching for the sun – Is it time to invest in fusion, to talk about why they have opted to take a bet on the fusion sector. Christopher Mowry, chief executive of Type One Energy, which has TDK Ventures as one of its investors, also joined, speaking also, in part, in his role as chair of the global Fusion Industry Association. Oded Gour-Lavie, CEO and co-founder of NT-Tao, a fusion startup backed by Honda and US energy company Delek, was also part of the panel.

This is what we learned:

1. We are seeing a democratisation of fusion technology

“Scientific advancements have been good over the past few years,” said Seibold. “But I think an even more important transformation that we’re seeing at the moment is the democratisation of the fusion technology.”

The development of fusion technology is no longer just the preserve of large national or academic institutions. Small startups can also do meaningful work in this field because of technologies like high performance computing in the cloud, which makes simulating new reactor designs quicker and cheaper.

High temperature superconductors are also becoming available and additive manufacturing is allowing for more complex reactor designs. Fuelled by the new venture investment as well as increased public money, young and nimble companies are coming in to develop fusion on shorter timetables than before.

2. Stellerators are the fusion technology most are betting on

There are several approaches to fusion, including magnetic confinement in reactors such as tokamaks and stellerators, as well as inertial confinement, where atoms are targeted with lasers. Inertial confinement was the method that resulted in the breakthrough at the US National Ignition Facility. But many investors are converging on stellerators as one of the most promising methods for commercialising the technology.

Stellerators are most likely to lend themselves to one day providing stable energy to the power grid, said Seibold. The Wendedelstein 7-X stellarator was shown to be able to hold plasma stable for eight minutes, whereas inertial confinement creates very brief bursts of energy. Seibold said that while the early breakthroughs of inertial confinement are impressive, “the way to a long term viable energy supply will be a much longer and harder one for those inertial confinement technologies.”

Tosukhowong agreed: “Seeing the advancement that has come out from stellarator community in the past several years, I think this is a pretty good bet that hopefully can be accelerated. It might be the only viable method to get the kind of steady baseload of energy that would replace coal fired power plants.”

There may, however, be several variations of stellarator. NT-Tao, run by Gour-Lavie, is building stellarator-based technology with a twist.

“We are taking stellarator further,” he said. “Density is a key in any magnetic confinement — hot, high density plasma will enable much more efficiency in the output. And to get to higher densities we’re taking advantage of new technologies like super strong power electronics that can really enable very fast heating of the system. It requires not a regular stellarator but one that can work in a dynamic mode where the heating and confinement work together. We’re having great breakthroughs in that.”

Gour-Lavie said another advantage of the dynamic stellarator system is that it works better and more efficiently at a small scale, which means this kind of power source could be built with fewer resources.

3. Investors should consider multiple fusion bets

Even though stellerators might be emerging as the fusion technology many investors want to back, there is still scope to take multiple bets in fusion, especially for companies in the fusion supply chain.

Not every fusion company is trying to be a soup-to-nuts producer of the whole system, said Mowry.

“In the last few years you’ve seen the emergence of companies like Kyoto Fusioneering that are not trying to develop an integrated fusion solution but focused on being a supplier of key technology elements,” he said.

“One can certainly imagine an investor investing in both a tier one company, which is really making a bet on the actual architecture of the solution in totality, but also separately making more than one investment in the supply chain of fusion, which as the industry grows up, is really emerging now as a critically important dimension to commercialisation.”

4. Energy is the big market and the only one worth gunning for

There are other uses for fusion, such a producing medical isotopes or providing propulsion systems for spacecraft, but these are tiny compared to the prospects of the $1tn-a-year market for energy. Most investors are only interested in the fusion companies looking to disrupt the energy sector.

“None of these other adjacent sectors offer anywhere near that level of opportunity of impact on society,” said Mowry. “The biggest impact that fusion can have on society is to create a practical path to net zero. Most fusion companies that I know of that are part of the the Fusion Industry Association are really focused on that.”

5. Picking the right nuclear fusion startups is a technical task but also about people

Seibold, who is about to announce Hitachi’s first fusion investment soon, said the team spoke to many sector experts as part of the evaluation. But, in many ways, finding the right startup to back came down to the same techniques investors have always used.

“At the end of the day, I come back to an old rule that I learned when doing independent venture capital: you always have to recognise patterns. For some technologies, the investment time is ripe when you see several companies coming up with a very similar approach. Then, you better look for the best team and the best consortium,” he said. “Yes, technology due diligence is very important. But I believe equally in the importance of being surrounded by the right people.”

6. You can expect an exit from a fusion investment in 10 years. Yes, really.

Given that fusion is still a nascent technology, many have questioned whether a typical VC fund with a 10-year timeline would be able to get a return in time. But both Tosukhowong and Seibold have done the analysis and believe it can be done.

“I think there’s a consensus that we will see working prototypes by the end of the decade, and prototype reactors that actually feed into the energy grid in the first half of the 2030s,” said Seibold. “Then commercially viable plants by the second half of the next decade.”

Both Tosukhowong and Seibold believe there will be opportunities for exits as soon as there are working pilots.

“Once a pilot plant has shown that it is working, there is strong potential that a utility company would be willing to take over the running of these, and putting steel in the ground in the early 30s,” Tosukhowong said.

“We actually would expect that there will be strategic acquisitions upon the successful delivery or proof of concept, starting in maybe 2026 or 2027,” said Seibold. “We may see IPOs in very early 2030s and then mainstream financial liquidity starting somewhere in the middle of the next decade. So that timeline and exit opportunities should match the fund lifetime that we have.”

An additional bonus, Mowry said, is that when and if fusion does take off, it has potential to scale fast, and faster than the nuclear fission sector did.

“One of the challenges of traditional nuclear power is the supply chain has very tight regulatory restrictions on it. One of the advantages fusion has is that it is regulatory light and able to tap into existing technology supply chains. And that is why I am optimistic that fusion can really scale,” he said.

7. Corporate investors can dramatically accelerate fusion

Gour-Lavie says the involvement of the private sector can turbocharge development of fusion far beyond what could be done in academia and public institutions.

“With the private sector going in with billions of dollars, this is pushing all kinds of different approaches and that will show. I believe this decade will see some very big breakthroughs in fusion,” he said.

There is an opportunity for corporate investors to help startups source equipment like power capacitors, and to help with engineering challenges. Connection to the grid as well as helping with regulatory and safety issues are areas where a strategic investor can provide support.

“Strategic partnerships with companies like TDK or Hitachi create an opportunity for a fusion company to basically not have to reinvent the wheel,” said Mowry.

At the same time, corporate investors have an opportunity to learn how to be suppliers for what could be an enormous future fusion industry.

“We are learning new things every day, like that they need magnetic components and that they need to handle super low temperatures and some super high temperatures,” said Tosukhowong. “There are so many new areas and applications that we’ve never been in. We we want to learn and develop electronic components that would be useful for startups in the future. This is the new mega trend and they’re going to need new materials, new components and all kinds of engineering capability.”

8. Let’s try to avoid a big hype cycle

No matter how careful your analysis, investing in fusion is still a bet, said Seibold. “And my biggest worry is that the investment community may not be prepared for that.”

Compared even to difficult sectors like biotech and semiconductors, fusion will have longer timelines. Couple that with technology investors who are well known for getting sucked into the hype cycle of first over-optimism and then disappointment, and you have a potential problem.

“I think what’s really important here is that the investment community really be eyes wide open about the amount of work that needs to be done to take the technology over the goal line,” said Mowry.

Watch the full webinar here:

This webinar is part of GCV’s The Next Wave series of webinars. We run a webinar on the second Wednesday or every month, alternating between advice for CVC practitioners and deep dives into specific investment areas. Our next webinar will be CVC portfolio-parent partnering – Driving the landing pipeline on January 10, 2024. Register here to secure your place.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).