Both models are gaining popularity — but which is right for your company? It depends on the business need and the stage of the startup.

Large companies are increasingly interested in collaborating with startups. But what is the best way to do this?

Two different paths have been growing in popularity over the past few years: investing in a startup and then collaborating with them on projects, or simply collaborating without the equity investment, an approach known as “venture clienting”.

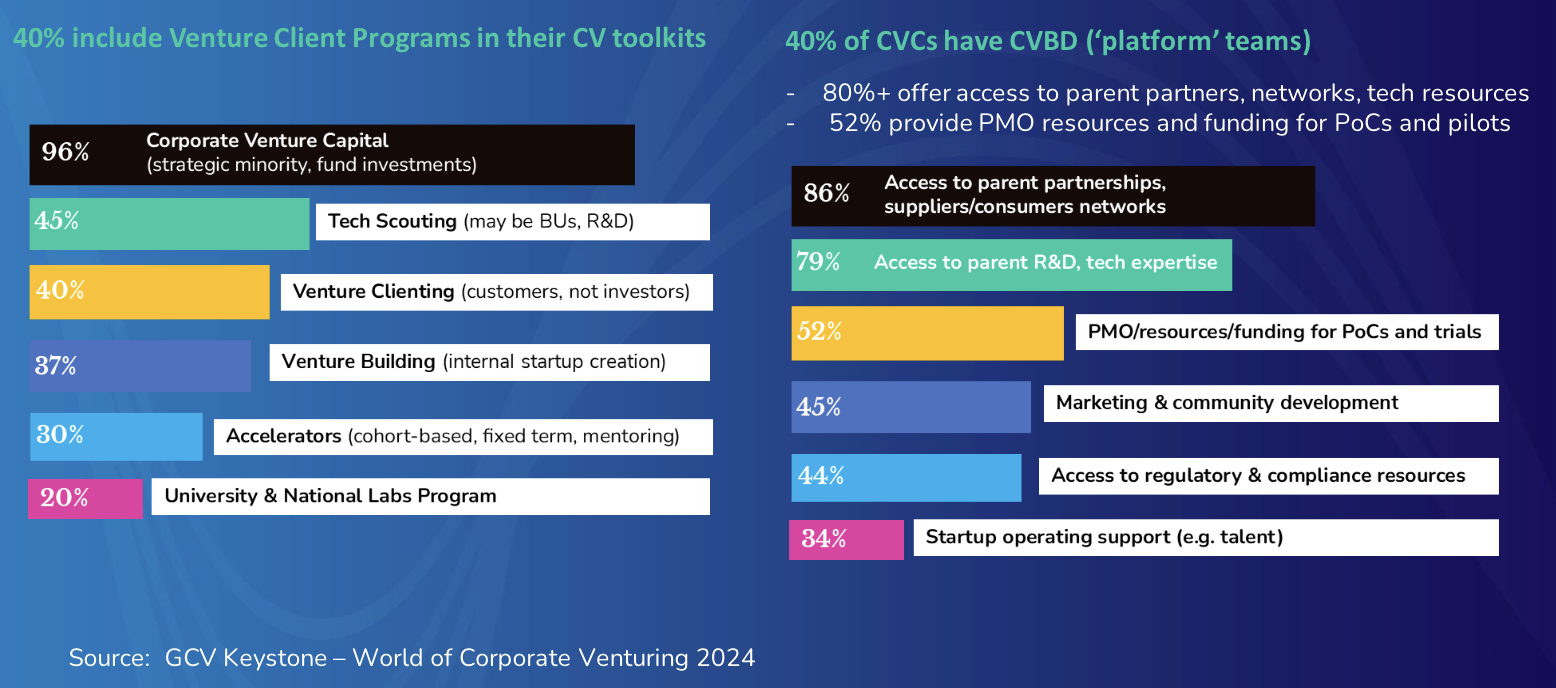

Companies that have made VC-style equity investments in startups have become increasingly keen to make sure that those portfolio companies progress to having some kind of working relationship with the business. According to data from the latest GCV Keystone survey some 40% of corporate venture units now have an integrated professional business development or platform team that pushes partnering between the startup and corporate.

Inga Grieger, for example, is one of a growing number of business development managers hired by corporate venture units, in her case at BMW i Ventures. It is a role that BMW i Ventures created some three years ago after realising that the companies in the investment portfolio were not making the most of opportunities to work with the carmaker.

“What I learned in these three years is that it’s a challenge to find the right persons, the right needs for and the right timing [at BMW]. The models and processes in the mobility industry can be very complex,” says Grieger. Startups can find this hard to navigate. “So this is why we stay longer with our portfolio companies and knock on many doors in the company to find the right partner.”

At the same time, many large companies have developed “venture clienting” units where they can partner quickly with a number of small startups without investing in them. This is somewhat different from a normal supplier relationship — with younger startups it is often necessary to have different, lighter touch procurement processes and the collaborations are more experimental.

Siemens Energy Ventures set up its corporate venturing team when it spun out of Siemens as a separate energy-focused company, and added a venture clienting function shortly afterwards, in 2021, led by Eva Harasewycz, so that it could address slightly different times of innovation needs.

JetBlue Ventures, led by Amy Burr, has had CVC operations and venture clienting from the outset, managed under the same umbrella.

Though the two collaboration models sound similar on the surface, in practice there is surprisingly little overlap, says Burr. These are two tools for very different situations.

“We have done proofs of concept with 50 companies and invested in 55 and the two areas are not overlapping much,” she says.

Grieger, Harasewycz and Burr joined our recent webinar Collaborating with startups: CVC platforms or venture client programmes to explain how these tools differ. These are some of the key points from the talk:

1. Venture client units allow companies to explore more technologies

The venture clienting practice at Siemens Energy Ventures only started in 2021, but, says Harasewycz, it has already overseen more than 78 pilot projects between startups and the parent company. Some 40% of these projects resulted in Siemens going on to adopt the technology or take the partnership further. Harasewycz estimates that the programme has generated some $80m in financial impact for the company.

This has been one of the key selling points of venture client operations. As Gregor Gimmy, founder of 27Pilots and one of the ‘godfathers’ of the venture client movement, told GCV back in 2022, CVC units will only invest in a handful of startups each year, but by using a venture client approach, a company can explore 10 times the amount of new technology.

2. But investing in startups still has value

Why invest in startups at all if you can partner with hundreds of startups through venture clienting without having to hand over any capital? It is a question that CVC teams get asked often, but Burr has a ready answer for this:

“We invest so we have a seat at the table, and we invest in early-stage startups so we can help them develop a product that actually works for the industry and for us. We get a lot of benefit from working very closely with a startup that we’ve also invested in. They will build things for us, we will get a first mover advantage,” she says.

“We never, ever tell a startup that they can’t work with other clients within the travel industry. There is definitely no exclusivity, but because we’re part of the conversation, we can help influence how it’s going to be developed, and that helps us.”

3. Venture clienting is more of a pull – CVC investing is a push

Venture client and CVC platform development are used in very different ways to solve quite different corporate needs. “It’s a push versus a pull”, says Burr.

The venture client — what Burr calls the ‘operations’ team — works closely with the business units to find a need to be solved, and then will go out to look for startups that would match that.

The starting point for venture clienting at Siemens Energy Ventures, too, is consulting closely with the business unit, says Harasewycz. “We generally do bigger market analysis studies to keep us strategically aligned on trends. But, for each use case, we have a dedicated person [who works with the business unit].” That scout, says Harasewycz, “needs to hear what the person in the business actually needs.”

Meanwhile, says Burr, the investment team at JetBlue “will scan the entire horizon of travel tech and find interesting things that they think are the next things to come along,” says Burr, and then suggest these to the company.

Having both is a way of making sure that the company fixes immediate problems but also does not get blindsided by the arrival of some disruptive new technology.

4. The CVC investors and venture client teams look for different companies

The venture client team generally looks for more mature startups — they need to already have a product and preferably one or two customers.

“We’ve looked at thousands of startups in my team so far. And what is really success criteria for startups to work with us is a certain level where there is a product, there is already maybe one or two customers that have tested this. If not, it will take longer to make this successful and even scale up through our facilities or with customers,” says Harasewycz. ”The more mature a startup is, the better we can take this off after a pilot.

In contrast CVC investors can invest earlier – before a startup would yet be ready to engage with the startup commercially.

5. Platform teams don’t get as involved with the pilots and proof of concept projects

Although Grieger at BMW I Ventures is focused on getting her startups working with BMW, she has clear boundaries for her role to avoid conflicts of interest. She will coach the startup and help connect them to the right person at BMW, but then will leave the two parties to take things from there.

“I typically take over after we did the investment and support our portfolio company, so that we find the right partner on the corporate side. Then I let it go. We are not involved in any procurement decisions,” says Grieger.

6. Venture client teams spend a lot of time coaching the company on the art of running a pilot project

In contrast, venture client teams often spend a good deal of time handholding business units through the process of designing and running pilot projects of proofs-of-concept with startups.

“What we found really early on is that the folks at JetBlue just didn’t understand how to actually do a proof of concept. This needs to be short and quick to try to figure out if it’s solving X, Y and Z problems,” says Burr.

Proof of concept projects need clear metrics that can help build a business case for a long term partnership. And if it doesn’t work, the company needs to be quick to move on.

Burr and her team also developed some tools such as a short-form proof of concept contract that skipped some of the more stringent legal requirements to get projects going faster.

“We spent a lot of time with legal to make them understand that this isn’t like a full implementation, this is just a quick test. The most minimal thing that we can do to make this work, is what we’re looking for.”

JetBlue Ventures will even pay for the proof of concept projects if it helps get things going — and generally does this through warrant deals in which it will take equity in the startups in return for footing the proof of concept bill.

At Siemens Energy Ventures Harasewycz developed a template outlining the KPIs and milestones for the proof of concept project that would keep the scope manageable and make it easier to evaluate.

“My team always sets a clear timeline and also KPIs that we need to meet in the project to evaluate [whether] we want to move on, and what’s the next step,” she says.

They also spend a lot of time consulting with the business unit involved with the collaboration, coaching them on how to run the project.

“We talk to the business about how it is going to look …and we consult our company to keep it simple so it doesn’t cost so much,” Harasewycz adds.

These were just some of the many insights from the webinar. Watch the full discussion below:

This webinar is part of GCV’s The Next Wave series of webinars. We run a webinar on the second Wednesday of every month, alternating between advice for CVC practitioners and deep dives into specific investment areas. Our next webinar will be: Media for equity – why it can work for your startups. Register here to secure your place.

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).