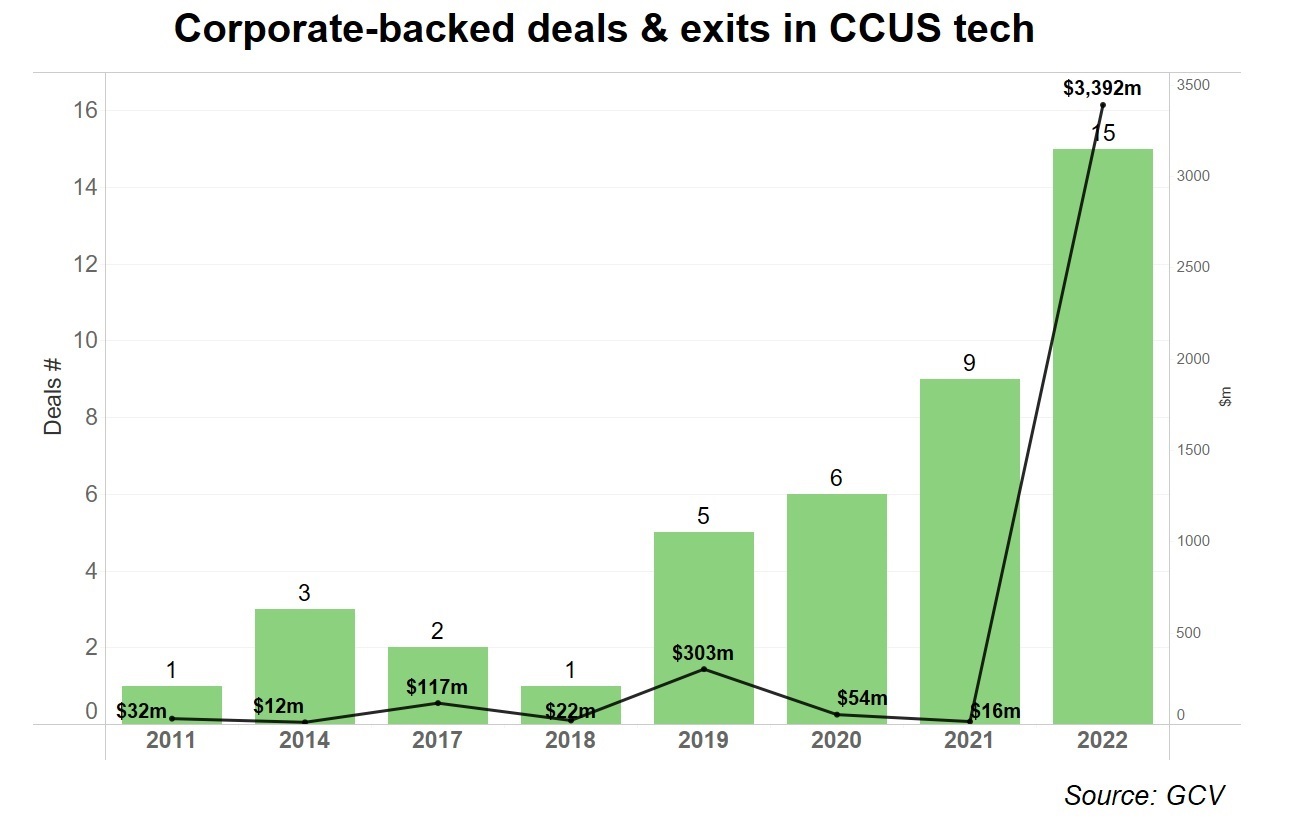

Large corporates are investing heavily in carbon capture projects as the technology becomes ready for the mainstream.

Late last year Canadian carbon capture company Svante raised $318m in a late-stage series E funding round that showed how close the company’s technology has come to becoming commercially viable.

The financing will support Svante’s commercial-scale filter manufacturing facility in Vancouver, Canada, which is anticipated to produce enough filters to capture millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide a year at hundreds of large carbon capture and storage facilities.

Chevron New Energies, a corporate venture arm of the US oil major, led the deal that values the startup at more than $1bn. Chevron first made an investment in Svante in 2014. Eight years later and 15 years since Svante was founded, the company’s long journey towards commercialisation is becoming a reality.

Carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) has become a key part of emitters’ carbon reduction strategies. The technology is the only solution for large emissions reductions from cement production, according to the International Energy Agency. It is also the cheapest way in certain regions to reduce emissions in iron, steel and chemicals making, according to the agency.

And now carbon capture is on the cusp of being able to be deployed at scale because of technological breakthroughs that make projects smaller, faster and cheaper.

“The challenge comes in making carbon capture accessible to smaller emitters at a reasonable price,” says says Iain Tobin, chief corporate officer and CFO of Carbon Clean, a UK-based carbon capture and storage startup which makes modular products that can be mass produced.

The International Energy Agency predicts carbon capture, utilisation and storage will account for between one quarter and two-thirds of emissions reductions in heavy industry. The use of carbon captured from emitting industries will also be a big industry. By 2070 nearly half the global energy demand for aviation will be met by synthetic fuels requiring the capture of 830 million tonnes of CO2 for use as feedstock, the agency predicts.

Svante latest financing round attracted several large corporate investors including 3M Ventures, Samsung Ventures and United Airlines Ventures, reflecting the application of the technology across a range of industries.

Svante uses a proprietary process involving solid sorbents made from metal-organic frameworks to capture CO2 from industrial flue gas. The gas is then prepared for storage or further industrial use.

Chevron has been a particularly active investor in carbon capture technology. Through its venture arms, it has made several investments including in carbon capture startups Carbon Engineering, based in Canada, and the UK’s Carbon Clean.

In May last year it announced a project to install carbon capture equipment at a cogeneration plant in Kern County, California, where it will capture and store emissions thousands of feet underground.

The oil major has made the technology a key plank of its carbon reduction goals. In a release, Chevron says carbon capture and storage is needed in energy and other industries to help meet the global aims of the Paris climate agreement, the legally binding, UN-brokered deal to limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius.

“Chevron supports the Paris agreement, and we and our portfolio companies in this area, such as Svante, Carbon Engineering and Carbon Clean, are working to drive innovation to overcome the challenges of scaling negative emissions technologies driving demand for them. Now we need 100 more Svantes and Carbon Engineerings.”

Carbon capture is also taking off in Europe. Oil company Shell is working with Equinor and Total Energies on the Northern Lights project, which is developing infrastructure to transport captured CO2 and permanently store it under the seabed in the Norwegian North Sea. The project, which aims to go live in 2024, intends to store up to 1.5 million tonnes a year of CO2. With its joint venture partners Shell will transport 800,000 tonnes of CO2 from Yara International’s ammonia and fertiliser plant in the Netherlands.

The demand for carbon capture is expected to eclipse all existing supply, making it a prime sector for investors. “Even if all suppliers of carbon capture technology were to scale up rapidly, there is still going to be a significant supply gap,” says Carbon Clean’s Tobin. “This is what makes the space exciting for investors and venture capital investors, because decarbonisation at the scale that is needed to protect the planet is going to need lots of different technologies and lots of different suppliers.”

IRA makes carbon capture economically feasible

Carbon capture may be at a crucial tipping point where it is ready to be widely deployed, but it is also surmounting a large cost barrier that made the technology prohibitively expensive in the past.

In August last year the US passed the Inflation Reduction Act, which ploughs $369bn of subsidies and tax incentives into clean tech. Carbon capture, utilisation and storage is one of the technologies that was given generous subsidies.

Previous tax credits for capturing and storing carbon dioxide emissions were in the $12 to $50 a tonne range. Under the new act, carbon capture facilities receive $85 per metric tonne of carbon dioxide emissions captured and stored from an industrial source; $60 a metric tonne captured and stored for enhanced oil and gas recovery; and $180 a tonne for carbon dioxide emissions captured and stored from a direct air capture facility ($130 a metric tonne for direct air capture used in enhanced oil and gas recovery).

The legislation also provides funding to subsidise the construction of carbon capture facilities.

The subsidies are viewed as a far-reaching incentive for emitters to invest in carbon capture. “It really changed the game for the whole industry, for people to get very serious about CCUS projects,” says Taha Syed Hussain, venture partner at Delek US, a downstream energy company. “We can see light at the end of the tunnel, that we can do these projects and make money. It is not just breaking even or doing carbon capture for non-economic reasons.”

The challenge comes in making carbon capture accessible to smaller emitters at a reasonable price.

Iain Tobin, chief corporate officer, Carbon Clean

Delek US was an investor in Svante’s latest fundraising round. The company is working with Chevron to capture CO2 emissions on cracking units inside refineries. It plans to install carbon capture at a refinery in Texas that is close to a CO2 pipeline, allowing it to transport the gas for either storage, or for other uses such as enhanced oil recovery.

Carbon Clean, which has built technology that captures carbon dioxide from industrial flue gases at the point of emission, has also attracted several corporate backers. Founded in 2009, it raised $150m in a series C round last year with Chevron New Energies taking the lead on the capital raise. CEMEX Ventures, Marubeni Corporation and Saudi Aramco Energy Ventures were also on the cap table.

Carbon Clean’s Tobin prefers to call the startup a “scale-up” because of its maturity. It differentiates itself from other carbon capture firms with its proprietary solvent, which it claims captures up to 95% of CO2 from flue stacks. When the solvent is heated, it releases the carbon dioxide, which can then be compressed for storage or used for other purposes.

Carbon Clean makes modular products that can be mass produced and installed easily at facilities of varying sizes. This makes the technology far less expensive than other carbon capture technologies that are based on bespoke designs for individual large emitters.

More than 60% of the world’s industrial sites are small and have limited space compared with the largest emitters. “What has really been missing in the marketplace is the ability to bring this same proven technology for carbon capture to a much wider range of emitters and urban sites where they can’t fit these bespoke designs,” says Tobin.

The company is focused on offering what it calls carbon capture as a service for emitters that do not want to operate a carbon capture plant. This means the company would finance the carbon capture plant, install it, maintain it and offer extra services such as compressing the CO2, transporting it, storing it or using it for different purposes.

The opportunity to use captured CO2 offers additional revenue streams for emitters. Tobin reels off a list of uses for CO2, including making shipping fuels and aviation fuels, vertical farming, food packaging and manufacturing potash to make cleaning products.

“It is a really common sense approach to use the carbon dioxide that would otherwise be released,” says Tobin.