Historically left behind by their peers in the golden triangle, universities in the north are stepping up with their own funds, accelerators and collaborations.

Northern England, with its 30 universities, should be an ecosystem of note. Time and again, politicians have spoken of the need to boost economic growth in the region. An ongoing strategy is the Northern Powerhouse – though this also, somewhat confusingly, includes parts of Wales and the fact that the official website still refers to an updated strategy that will be published in 2019 is emblematic of how much of a priority the north often is in Westminster.

It is therefore hardly a surprise that universities have started taking their fate into their own hands. James Kitson, head of commercialisation at University of York, noted that despite Northern Powerhouse being “a strange term”, it had helped with “the recognition that there is stuff going on in the north and attracting interest”.

He highlighted state-backed funds managed by Mercia Asset Management focused on the region but lamented that “the cash is spread thinly and time-limited”. The challenge, he said, was that “there is no concise idea of what the Northern Powerhouse area is and how it will be supported; it is all piecemeal. Cambridge, for example, has an ecosystem with people and funding lined up to get opportunities through the system. We do not really have that.”

While Kitson admitted he did not know the answer, he said: “I am not convinced that limiting ourselves to working in a geographical area like the north or a subset thereof is the best way forward because there is a huge advantage to working with people elsewhere. Aspect is a great example: we are not limiting ourselves to local universities, we are learning from others.”

Aspect, led by London School of Economics, is a network for organisations looking to make the most of commercial and business opportunities from social sciences research. It also includes institutions such as University of Oxford.

Kitson acknowledged: “Northern Gritstone and Northern Accelerator are very useful, but diversity of options is important. We participate in North By North West, which is a great programme – we see that as a key activity. What is needed is a range of these programmes that we can all participate in, so that we can put our opportunities to the most appropriate one.”

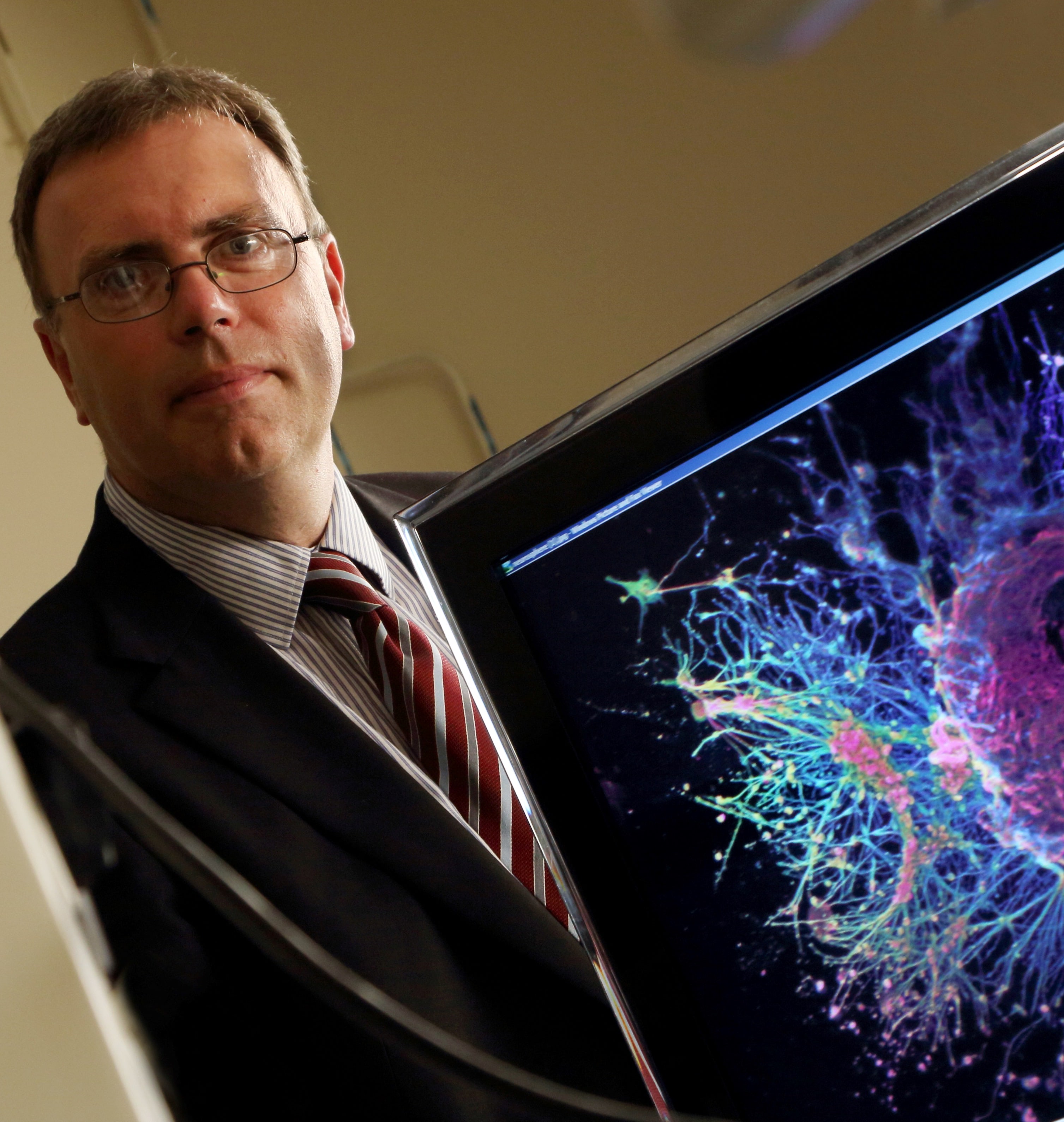

Kitson is particularly well placed to sign up to new initiatives: his position was only created a year ago when he joined from University of Leeds. “The opportunity to go into a Russell Group university and essentially build a tech transfer office from scratch is not one that comes up very often, so I was taken with that,” he explained his move to York. “And I have been proven right that there is a lot of great stuff going on here.”

Although tech transfer activities happened before his arrival, it was handled by the business development team which has a wider remit. “We have put a lot of thought into how we want to approach tech transfer at York and we have implemented a clear process of how we see it happening not just by formalising it but also putting it on the academics’ radar,” Kitson explained.

Already, he added, “York is very strong in knowledge transfer with industry. We have a very good Knowledge Transfer Partnership (KTP) programme and that team recently entered collaborations in Africa which, I believe, makes York the first UK university to be working with industry there through a KTP project.”

And York has produced spinouts in the past, with eight currently active. Kitson highlighted two, teasing that one was in the works he was extremely excited about too: “Simomics provides in-silico modelling software for the pharmaceutical industry to solve problems such as drug design and development. It is an interesting company, and its academic founders are leaders in their field. Simomics is on the verge of significant growth and I see them as high potential.

“Another one, which has not quite spun out yet, is Weavr. It is a collaboration between the university and a number of organisations, one being esports events producer ESL. There is a huge project funded by Innovate UK, due to complete later this year, to develop commercial applications. The technology is a suite of tools for real-time esports analytics.

“Esports games are complicated and there is a lot going on, so it can be difficult for commentators and viewers to drill down into the data. Weavr’s technology not only helps understand what is going on, it also makes predictions for the outcome.”

Long-term, Kitson revealed, his vision was to increase the output of commercialisation activities. “But,” he underlined, “I do not want to play a numbers game and generate companies for the sake of it; the same applies to licences. I want to impact not just commercial returns for the university but also the world through employment opportunities and benefits to society – support York’s core mission to do and build things for the public good.”

Keeping in line with that vision, Kitson continued, “we are not just looking at multimillion pound commercial opportunities, but also non-profits or social enterprises. York has very strong faculties of social sciences, and of arts and humanities, so we are looking at what we can do with these areas which traditionally do not generate a lot of commercialisation activities.

We have a lot of potential at York but it will require a bit of a cultural shift – as it will at a lot of universities – because many social scientists and arts and humanities researchers think commercialisation is a dirty word.

James Kitson

“We have a lot of potential at York but it will require a bit of a cultural shift – as it will at a lot of universities – because many social scientists and arts and humanities researchers think commercialisation is a dirty word.”

Physical space, investment and support for new businesses were all still missing from the region, Kitson said, but the university was working with partners to tackle all of them. He explained: “University of York, the city and Yorkshire have real strengths in biotech, agritech and bioprocessing. There is a lot of crop science research. We are leading an initiative called BioYorkshire with Fera Science and Askham Bryan College, and are looking for devolution funding to turn the county into the bioeconomy capital of the UK.

“There are high ambitions – we want to create 4,000 jobs and 800 startups and spinouts by 2030. Not all of that will come from the university, but it will play a key part. From a commercialisation point of view, that is a great opportunity to drive activity.

“We have a Connecting Capabilities Fund (CCF)-funded scheme called Thyme Project with Teesside and Hull, where we are looking at sharing knowledge and developing bioeconomy projects, which is going really well.”

All good things come in threes

The shift to an impact focus is one that is happening at other universities in the north, too. Andy Hogben, head of impact and intellectual property (IP) at University of Sheffield, said: “We prioritise projects based on their potential for creating impact as well as their abilities to generate financial return. If I rewind six years, we were entirely financially motivated but now it is very much an impact-driven agenda.”

He highlighted: “We have a team of 10 commercialisation managers working from across every faculty. We develop projects from arts and social sciences, as well as the more traditional engineering, maths, science and advanced manufacturing.

“The key thing that we prioritise is market discovery. We like to remind academics that you have to assume nothing until you have gone out, tested the market and spoken to people. That sometimes does not land very well, but it is part of the job.”

He added: “We do a lot of work with early-career researchers in that space, providing opportunities for post-docs and PhDs particularly through that market discovery piece. We like to hunt the entrepreneur that is in that community, as do a lot of universities.”

Sheffield reshaped its approach to commercialisation around four years ago, Hogben remembered. The university set up an internal investment budget – not a fund, he stressed – “that allows us to inject cash into proof-of-concept work, build up teams or even invest in spinouts. If you add up our patent and investment budgets, we have about £1m available each year to deploy. Introducing that was game changing for how we do tech transfer.”

The shift towards impact was an internal initiative, Hogben said, and came after a pipeline agreement with IP Group expired. “We looked at what we wanted to do with commercialisation and recognised that we wanted to maximise impact from all our research. This is not about generating Research Excellence Framework (REF) case studies.”

As with all offices, the pandemic led to fundamental changes – both positive and negative, as tech transfer is a contact sport. A positive change, Hogben said, was the ease with which his team could now talk to investors. He expanded: “We have done more than ever. We spun out seven companies last year, and five of those have raised decent funding. We also signed multiple licence deals.

“When you compare that to the fact that our historic trend is between zero and one spinouts per year, it shows the step up in activity. Dealflow has been climbing and it is now being sustained at that level.”

Two noteworthy spinouts in Sheffield’s portfolio, Hogben said, were Opteran Technologies and FourJaw Manufacturing. “Opteran is developing machine vision-based natural autonomy and the ability for drones to map out where they are. The underpinning research was on animal vision and they now have an optical flow collision avoidance system. They raised a seed round from IQ Capital, Episode 1, Seraphim Capital, and they are really going to grow quickly.

“FourJaw Manufacturing Analytics came out of the Advanced Manufacturing Research Centre (AMRC). They have an internet-of-things platform for helping machining companies improve their productivity and understand what is going on with their industrial machines.”

FourJaw was notable for a more unusual fact, too, Hogben revealed: “One of the two founders is one of our commercialisation managers.”

He added: “I love that it highlights how the commercialisation managers have to put their heart and soul into projects, and they become embedded in the team quite often. As the tech transfer office, it is good to think of yourself as a potential training ground for talent.”

Sheffield is also part of North By North West – led by Queen’s University Belfast, it also includes the universities of Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Lancaster, Ulster and Edinburgh. Hogben acknowledged that Sheffield’s capabilities in market discovery were partially due to that partnership, quipping that “at Sheffield, we are good at talking to people at other universities and pinching their ideas, or talking to industry and making sure that we receive proper feedback on our commercial projects.”

Among Sheffield’s flagship initiatives is also the aforementioned AMRC, located in the innovation district on the outskirts of the city, which has 125 industrial members. Hogben explained: “It is a very collaborative way of working with industry to make sure that everyone can develop technology in a pre-competitive manner. It is a fantastic initiative that has been running since 2001 and is moving into a second phase now.”

Taking a wider view, Hogben declared: “This region is incredible and a genuinely collaborative space. Yes, we are all a bit competitive with each other, but we have this view that we are helping each other for the greater good – everyone I speak to in this region buys into this.”

Hogben added a less obvious point to his argument, at least in a tech transfer context: the need for better trains. “This is a serious point,” Hogben stressed, “because everyone always talks about how quickly they can get into or across London and the culture that creates. What we do not talk about is that I could be in Manchester with these other hubs and resources available to me in the same time it takes someone to get across London.

“We do not talk about these cities like they are linked up in that way. Part of that is because of bad transport infrastructure, but I am a firm believer that the big cities should be tying together.”

And combining the strength of the universities of Sheffield, Manchester and Leeds is exactly what Hogben helped do through the creation of Northern Gritstone, an independent investment company that will back spinouts from the three institutions.

“Northern Gritstone is going to be absolutely game changing,” he declared. “It is really what we need to start thinking about as a region or the Northern Powerhouse – it is not about individual cities; it is about the whole area.”

The launch target for Gritstone is £150m ($210m). Hogben clarified: “It is not a fund being raised by an existing management team, it is a new standalone company. It will invest off its balance sheet and have the ability to be patient and take reasonable risks, without the pressure of having to recover the money within a certain time.”

Andrew Wilkinson, chief executive at University of Manchester Innovation Factory, the institution’s wholly-owned tech transfer subsidiary, added: “Northern Gritstone is much like Oxford Sciences Innovation – although there are some differences – and ultimately we would like to raise around £500m.”

Capital was a significant constraint in growing businesses in the north, Hogben maintained, and Gritstone was expected to bring in co-investors. “We are missing access to patient capital with a decent risk appetite. It sounds like we are struggling to raise money all the time and we are not – we have to go to that extra level of effort to attract the money. You have to travel, or at least you did pre-covid, and you cannot just go 10 minutes down the road.”

Wilkinson drilled down further, stating: “Manchester is not Cambridge or Oxford, and that sounds perhaps an obvious thing to say but if you take the angel investor community in, for example, Cambridge, it is highly likely that they will have made their money in a technology.

“When you talk to them about the processes and the time to take a new piece of synthetic biology to market, for example, they understand all of those things. In Manchester, angel communities have often made their money in retail, property or finance, and therefore they do not have a fundamental understanding of what deep tech is about.”

It was not all doom and gloom, he pointed out: “There are good efforts going on at the moment to try and build angel investment networks, to work with people who have an interest, curiosity and ability to put early-stage money into companies.”

Why did Manchester, Sheffield and Leeds team up with each other? Hogben revealed: “When you talk orders of magnitude, we are similar-sized institutions. We operate in a similar way – we are research-intensive, top of the league tables, and have similar structures and histories – and we have dealflows in similar sectors, for example energy, so we can build Northern Gritstone around this.

“Expanding it is something that we have talked about, but it is not in the immediate plan. We need to prove that the idea works and we are certain that we have the dealflow from the three universities that we need to raise and, importantly, deploy the money.”

Wilkinson echoed these thoughts: “Never say never, but we want to bed in Gritstone first, have our first raise and get our processes functioning. We are currently recruiting a chairperson and a CEO, and we will shortly be recruiting a chief financial officer.

There are good efforts going on at the moment to try and build angel investment networks, to work with people who have an interest, curiosity and ability to put early-stage money into companies.

Andrew Wilkinson

“Ultimately, Gritstone will make its own decisions. If it is the right thing to do for the investors, I am sure it would consider working with other universities. The important thing is to get the fundamentals right before we start doing that.”

The relationship with the three universities is contracted for 15 years and each institution holds a 2% golden share.

Although the origins of Gritstone predate Wilkinson’s arrival at Manchester, he has led fundamental restructuring efforts at the office. Still known as UMI3 when he arrived in early 2019, the unit counted about 42 staff. “I took it down to 17 and rebuilt it from there,” he said.

Like his peers at York and Sheffield, Wilkinson stated: “Our mission is impact. We do not care about how many patents we file, what we care about is whether our companies will go out and raise investment and our IP will get licensed.”

When spinning out companies, “we employ a stage-gate process, a particularly commonly used approach in Europe and the US, where you move through set phases and ask a range of questions for each one before a panel of experts allows it to proceed.”

Of those spinouts, Manchester expected to launch around 12 this year, Wilkinson said, “so we are growing significantly.” An existing spinout was how Wilkinson, who previously worked in industry, ended up at the Innovation Factory: he joined Graphene Enabled Systems as CEO in 2016 to help it commercialise a portfolio around 2D materials technology – particularly graphene.

Graphene may be one of the best-known innovations to have come out of University of Manchester to date. Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, who made the discovery in 2004, went on to collect the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010 for their work.

Manchester’s goal is to produce around 25 spinouts annually within four to five years. Northern Gritstone would be “vitally important” in that endeavour, Wilkinson declared. “In fact, it is not doable without Northern Gritstone.”

He explained: “One of the things that Oxford Sciences Innovation has demonstrated is that if you make a lot of capital available, it has an amazing effect on academics. And OSI’s contribution to the AstraZeneca vaccine is a good indication that not only is it good for the academics, it is also good for the investors as well.

“A lot of our businesses are deep tech and take a long time to get a good return on. Many funds have a lifecycle of 10 years, so you are never going to get the amount of money to scale a business to a point where it is really valuable. Others are closed-end funds, so you do not have the opportunity to get the return you want.”

In a nutshell, Wilkinson summed up, “the ability to put more counters on the roulette table is really important in this space. We have lacked that not because of the quality of our science or the quality of the opportunities, but simply because we have not been physically close to that level of investment.

“What we do have, which is a great advantage, is access to life sciences. We have access to a devolved healthcare system, which means that we can make our own decisions. We have a lot of industry. Although we have some disadvantages, we have some real advantages. And we have physical proximity and great science.”

He concluded: “Manchester is a big university in the top 50 in the world, there is an awful lot of opportunity for investors or for industrial companies to come and work with us. We are fortunate that we have the scale to cover a broad range of areas, across the faculties of humanities; biology, medicine and health; and science and engineering. We come up with good solutions to people’s problems. It is an exciting place to be.”

Finding executives is half the battle

The universities of Durham, Newcastle, Northumbria and Sunderland have been tackling a different challenge first: finding the right talent to lead their spinouts – a programme that grew into Northern Accelerator. The Executives into Business initiative began at Newcastle, David Huntley, head of company creation at the university, told GUV: “It started about six years ago. We had gone through a phase of creating spinouts which, by and large, were either not great successes or failed.

“We had an ‘enough is enough’ moment and said we are just not going to do this anymore unless there is a management solution. By that we meant that we would not spin out a company unless the academic or tech transfer team brought in an external businessperson to run the spinout or one of the academic founders left the university to do it.

“We were no longer going to accept an academic running a business in their spare time. We adopted that as a firm policy and the idea of Executives into Business was born.”

Initially they had to attract talent through a sweat equity arrangement, Huntley noted, but this often meant that people who would have been a perfect fit were unable to dedicate several months to pulling together a business case without a fee. But, he added, “it was the seed that germinated into Northern Accelerator, which originally was a European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)-funded programme solely to offer the Executives into Business support. It meant we could pay these people a fee and that has been a game-changer.”

It certainly changed things for Newcastle. The university currently has 27 active spinouts, having generated five spinouts during lockdown – Dragonfly Insulation, ScubaTx, GlycoScore, Indicatrix and XR Therapeutics. It expects to unveil another three by the end of June.

The portfolio covers a spectrum of industries: the aforementioned Dragonfly, for example, is working on silica aerogels for use as fire retardant insulating materials. Others include Advanced Electrical Machines, which is developing sustainable electric motors manufactured without rare earth materials. Newcells Biotech specialises in human stem cell models, while AMLo Biosciences is commercialising an early-stage prognostic test for melanoma.

Northern Powerhouse, Huntley pondered, had “helped to raise the profile of the north and contributed to the government’s ‘levelling up’ agenda”. However, there were “no specific discernible benefits to our commercialisation activity”. He added: “The northeast obviously lags behind most areas of the country in terms of many metrics of wealth creation and entrepreneurship.

“Historically the northeast, through its universities, is rich in world class research but underserved in terms of innovation, that is the commercialisation of that research. Northern Accelerator is addressing this challenge.”

Northern Accelerator’s programme lead is Tim Hammond, director of commercialisation and economic development at Durham University. He recalled: “I led on a bid for money from Research England three years ago and I managed to secure £5m through the CCF programme.

“Around the kernel of the Executives into Business programme, we built the accelerator with an Ideas Impact Hub to encourage early-career academics to embrace commercialisation through to the Future Founders programme, which is working with academics a bit later in their career where we help them shape their ideas.”

He declared: “We find we are now getting not just the usual suspects but a much broader base of researchers who are starting to engage with that activity.”

There was more still to the accelerator, he continued: “We also put in place Pre-Incorporation Funds and we run an open competition where we put in feasibility and proof-of-concept funds to move ideas towards incorporation. That could be making a prototype or a critical bit of R&D – we have funded 50 of these with just over £2m. It is a tough panel of internal and external experts that researchers have to go through.”

There were moves to expand the Executives into Business programme, Huntley and Hammond revealed, and incorporate an additional university into the accelerator. But this would be contingent on securing additional financing through CCF, news of which are not expected until May.

Much like Northern Gritstone, Northern Accelerator is also looking to tackle the challenge of patient capital. The latter, however, has chosen the more traditional route of recruiting a VC firm, Northstar Ventures, to raise and manage a vehicle of around £75m. Northstar is already managing a £1.7m seed fund – launched last August and expected to be fully deployed by June – for the accelerator. The larger fund would have a seed component, Hammond said.

The combined strengths of Durham, Newcastle, Sunderland and Northumbria provided a pipeline of deals that could sustain a £75m fund, Hammond added: “For the four years prior to the launch of Northern Accelerator, the average number of spinouts out of Newcastle and Durham was less than two per year. Last year, we set up 10.”

He clarified: “As individual universities in the northeast, we all have tech transfer offices and they work as separate entities. We have always been reasonably well connected because the northeast is a small region, a long way from many places. What we have been doing over the past four years is really putting together more of a joined-up ecosystem.

“The Northern Accelerator journey has been about having access to systems so we can move things through our universities and really punch above our weight with a combined pipeline that has critical mass.”

Durham, whose strengths include a partnership with Procter & Gamble that has found recognition as far as in the US congress, is not just focusing on spinouts in traditional sectors either. One of its companies, Rescribe “has developed bespoke optical character recognition software to digitise and interpret images of text in early modern – 16th to18th century – books. This allows researchers to gain access to knowledge within collections that would otherwise be inaccessible,” according to Hammond. “It is a small business, and it is not going to be turning over a lot of money, but it has several contracts with curators of valuable European book collections.”

Northumbria, meanwhile, unveiled a new medtech spinout, PulmoBioMed, in March this year. Chelsea Brain, IP commercialisation manager, said: “It is challenging to do spinouts generally because the academics have to have the appetite for them, you have to find the right management team and it has to be the right opportunity to put into a spinout.

“Most universities naturally only do a few spinouts, but we want to make a step change in the number coming out of Northumbria University.”

Northumbria’s tech transfer operation is relatively small – led by Brain and fellow IP commercialisation manager Hugh Rhodes – and, Brain acknowledged, “in comparison to the likes of Durham and York universities, we might be the smallest team. But that means we are really busy because Northumbria, over the past few years, the research base at Northumbria has been growing significantly.

“We have started to see more and more ideas coming through – high-quality research that has commercial potential. We are snowed under to be honest, but it is always good to be busy and we are bringing new staff into the team as soon as we can.”

And the quality of spinouts that is coming out of Northumbria is clearly on a high level. “PulmoBioMed’s technology collects exhaled breath condensate – the water vapour in your lungs that you see on a cold day,” Brain explained. “That breath condensate contains a wealth of molecules and it can give you a picture of health.

“It is possible to diagnose all kinds of things from breath. Lung cancer is an obvious one, but breath also contains indicators relating to diseases like liver and breast cancers and obviously respiratory diseases like covid. That last one has been a major focus for the technology. Imagine being able to diagnose diseases like that noninvasively and instantly, that excites me.”

The spinout secured Innovate UK funding to develop the technology and was now in the process of raising its first round, Brain said.

Northumbria was strong on nursing and psychology and had good links with NHS trusts, Brain added. “But we have also started to see things coming through in social enterprise and not-for-profit opportunities. We have been looking recently about how we can better support those kinds of ventures too.”

Brain echoed the thoughts of her peers when it came to challenges faced by the north: “We are not short on skills and we are not short on innovation. We have brilliant graduates. The problem is that we lose them to other regions.”

She revealed: “I talk from experience. I graduated from Newcastle and I had to move south to start my career because that is where the companies were.

“But it is changing. Investors are looking at new areas in the UK. You can see the potential in the north. This image of ‘it is grim up north’ is almost gone and rightly so.”

Brain offered some international perspective on the north’s challenges, noting that she spent time in New Zealand looking at university enterprise. “There is a push there to move the economy away from being a country that relies on agriculture towards knowledge-based businesses. I found that interesting because that is something the northeast is also wanting to do.

“What I admired in New Zealand is that the country recognised how important universities were for making that move. There was a huge emphasis on enterprise training from undergrads through to top-level academic staff. Those graduates were leaving university with an entrepreneurial spirit and a good understanding of business.

“That is the right starting point to grow innovation businesses in a country or in a region. And that is maybe something that we could do better.”

It was not something that could be exclusively solved by Northern Accelerator, she declared. “There are training aspects in Northern Accelerator. It is helping, but it is not accessible to undergrads for example. It has to be down to government policies and universities incorporating that training into every single element of their courses.

“Our university does provide exposure now, especially as an undergrad, to enterprise training, even as part of a science degree, for example. But it will take time for those people to move up the academic ladder and to have that experience at the top of the universities.”

Huntley, too, offered an international perspective: “In the communications we have with other European tech transfer companies, we are on an equal footing if not ahead.

“In my time within tech transfer, spinouts have gone from a Cinderella activity to a really important activity. It is a combination of universities having begun to realise they have technology they can exploit not only for their own benefit but also the wider economy, and having an obligation to play in that field.”

This was true across the UK, he stressed: “At the first university conference I went to around 12 years ago, we barely mentioned spinouts and at the last one I went to we barely mentioned anything else. It is a much more important agenda than it was 10 or even five years ago.”

Hammond was optimistic that Northern Accelerator would play a crucial part of building an ecosystem that not only attracted talent and money, but also ensured it would stay in the region. He said: “We are getting a lot of interest from the media and it is something we talk about. I have the innovation leads from the North East Local Enterprise Partnership and Tees Valley Combined Authority sitting on my advisory board – clearly, they are very keen to ensure what we are doing stays within region.

You cannot force businesses. They will stay if the environment is good and right, because there is provision, financing, investment, accelerators and incubators – keeping that infrastructure right is what we should be doing as a region.

Tim Hammond

However, he cautioned: “You cannot force businesses. They will stay if the environment is good and right, because there is provision, financing, investment, accelerators and incubators – keeping that infrastructure right is what we should be doing as a region.”

Durham, which is also home to challenger bank Atom Bank that built a close relationship with the university, already convinced its two Aim-listed businesses to stay local: Applied Graphene – which recently raised £6m – and Kromek, which recently secured £13m and even acquired two US-based businesses on their journey.

“It is very important those businesses can grow within the environment that they are.”

What is the future for Northern Accelerator beyond potentially more partners and a £75m fund? Hammond said: “We want to help our businesses scale up. Having funds which are focused on the universities and understanding the scale-up needs and growing pains of university businesses is part of what we are trying to achieve.

“It is also about looking at how we can build upon the Executives into Business programme to not just get an executive in at the very beginning, but whether we can modify the programme to help businesses grow. This is something we will start talking about more later this year.”

Brain meanwhile mused: “For me, the long-term vision for Northern Accelerator is to have a thriving commercialisation ecosystem in the region.

“We want notable commercialisation success stories and we want to see more flourishing Northumbria spinouts and preferably ones that stay in the region. That, for us, would be an achievement.”

Huntley looked ahead saying: “Northern Accelerator as a brand standing for effective and successful university commercialisation will remain and prosper as a collaboration of four or five northeast universities.

Huntley’s long-term ambition that the Executives into Business programme could go back to sweat equity might seem paradoxical at first, but he explained that currently “it is a way of paying someone £30,000 to come on board, develop a spinout and then run it. As we become more successful and have even better spinouts, we might not need that fee anymore – it is where we need to get to, really, to have that ecosystem.”

While the challenges ahead may have unique regional varieties, there is a common thread to this story that spans the north: there is no shortage of outstanding research and no lack of ambition. And while these universities may be at the beginning of a long road, they clearly have a map that points in one direction: phenomenal success.

For the north of England, finally, the time has come.

To help it get there, GUV will organise its first conference focused on northern England and Scotland in November 2021 at Heriot-Watt University in partnership with Umi and CPI. More information can be found on the official event website, GoFurtherIndex.co.uk, where tech transfer offices from the two regions can nominate their spinouts to pitch to investors ranging from angel investors to corporate venture capital firms.