More corporate investors are turning to seed-stage investing to get early exposure to new technologies. But it requires a different skill set to what CVCs are used to.

Photo by Vitolda Klein on Unsplash

Corporate investors typically tended to invest in later-stage startups — ones that already had a working product or were ripe for partnership deals. But in the past two years corporate investors have increasingly participated in seed stage funding rounds (earlier than series A), changing the perception of what typical corporate venture capital is interested in.

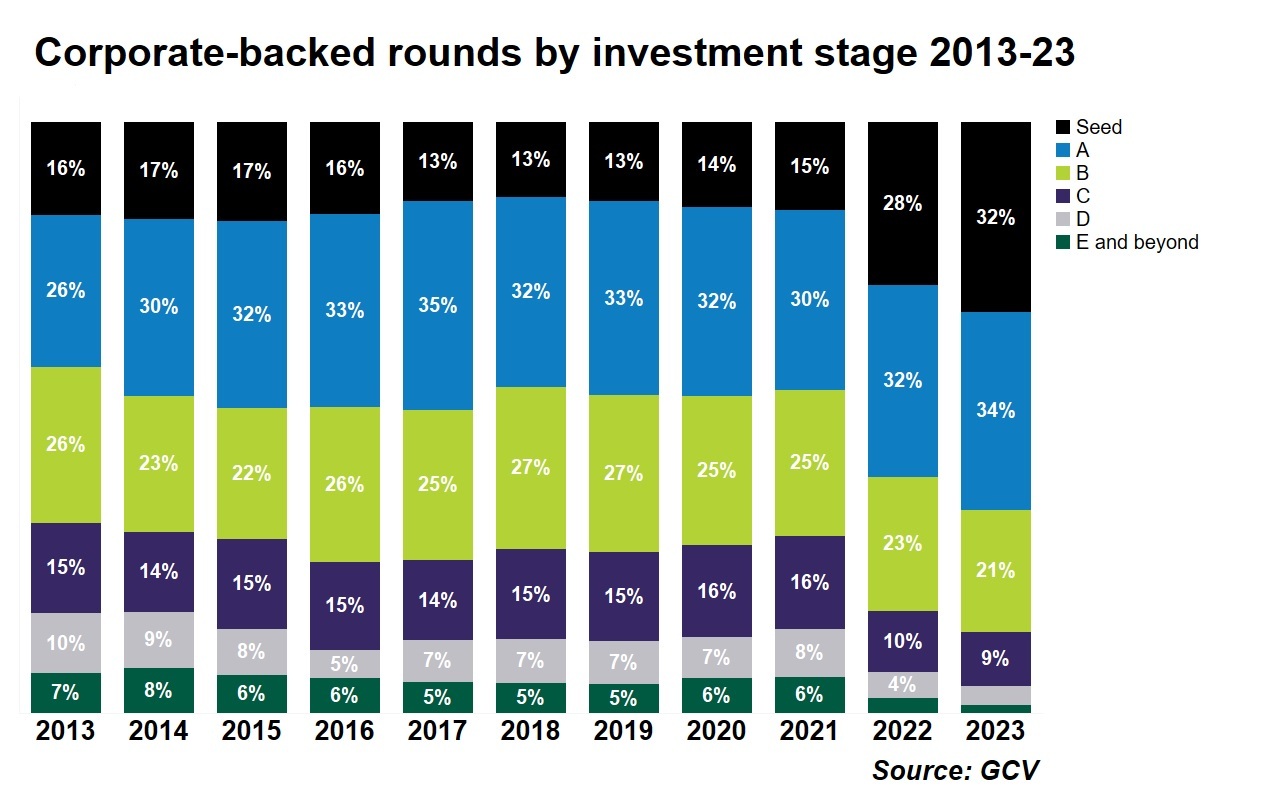

Seed stage funding rounds accounted for 32% of all the corporate-backed funding deals in 2023, according to Global Corporate Venturing’s Keystone survey data, more than double the portion seen in 2021.

Corporates have several reasons for shifting to investments in seed stage companies. One is the inflated valuations over the past few years for later-stage venture deals. “Where companies have been overvalued, it makes negotiation complicated and also raises risks of transactions not completing,” says Bruce Niven, head of strategic venturing at oil and gas company Saudi Aramco. The CVC recently started doing more early-stage deals.

Seed-stage investing also gives corporates early access to strategically important innovations. By investing in a high volume of early-stage companies, corporations have more exposure and visibility to many more technologies.

“Part of our mission is to educate the mothership about the latest technologies,” says Tom Gibbs, senior investment director of Debiopharm Innovation Fund, a seed investment fund for Swiss biopharmaceutical company Debiopharm. “The earlier you go, the further you see into the future.”

For newly launched CVC units early-stage investing is also about building brand. Cheque sizes are smaller for seed investments and companies can do a much higher number of transactions compared with later stage deals. In this way they can become better known in the market as an investor.

MS&AD Ventures, the corporate venture arm of the Japanese insurance group, was set up five years ago to do a seed stage investing. It does between 15 and 20 investments a year. “It is just really hard to build a brand and track record when you do three deals a year,” says Tiffine Wang, partner at MS&AD Ventures. “We did have to do some level of volume and we still do. We’re still hitting around the same pace.”

Investing in seed stage companies is different to later stage. It requires a different set of skills and operational approach. Here are six tips for doing it successfully:

You will need to tap into different networks to source deals

Sourcing early-stage deals requires corporate investors to connect with different networks such incubators, accelerators and research labs. Gibbs at Debiopharm Innovation Fund says his company has even considered hosting an accelerator or incubator in its new office building to get closer to seed businesses.

High-Tech Gründerfonds, a German public-private venture capital investment firm specialising in seed investing, hosts a lot of events and coaching sessions to get to know founders and potentially source deals. The fund, which has a number of corporate limited partners, also relies on its network of former founders of university spinouts as well as corporates that are spinning out companies. It made such an investment in a spinout from German conglomerate Siemens.

Seed investing is highly competitive, says Wang at MS&AD Ventures, requiring corporate investors to establish close relationships with founders. “Most of the really good deals have tier-one firms. The [founders] will be like, ‘why do we need to let you in’. That strategic value that you bring – they don’t always want to take your money because of that unless there is a really good relationship,” she says.

Due diligence requires a lighter touch

Because investors spend less money on seed investments and do a higher volume of deals than at later stage, they often do less due diligence. Some funds don’t have the staff to do due diligence on a high volume of deals. There is also often less information on early technologies to make a thorough analysis. Seed investment is also faster paced.

Gibbs says smaller cheque sizes means there is less perceived risk in an early-stage investment. The firm didn’t hire more staff when it started doing seed investments and so had to streamline its investment approach. It doesn’t go to an investment committee, for example. “We just have a couple of senior people that we run this by, and if the thumbs are up, then we go ahead and do the investment. This allows us to do many more investments,” says Gibbs.

READ MORE:

How to make the most of a smaller fund

Smaller corporate venture funds — those with less than $50m — can use their slim size as an advantage if they plan well and have a laser-like focus.

Be prepared for seed companies to pivot

Early-stage companies will often change their product or service as they are so early in their development. They also tend to fundraise more frequently than later stage companies, which corporate investors need to be prepared for.

Strategic investors often like seed investments because they have the opportunity to shape a product or service early on. “If you are already on board as a corporate, you can tailor the product much more to your needs,” says Gregor Haidl, principal at High-Tech Gründerfonds. “Whereas, when you’re entering in the later stages, you are one of many customers and the impact you can have is much less.”

In conservative sectors like the pharmaceutical industry being exposed to seed investments can influence the parent to be more agile. Gibbs at Debiopharm hopes the flexibility of early-stage companies to pivot their business models can rub off on the fund’s pharmaceutical parent. “Hopefully we can also have the flexibility and the agility ourselves to roll with the punches. This is part of our interest in doing a lot of investments and exposing the pharmas. It is culture change that we’re trying to foster because pharmas historically are rather conservative,” says Gibbs. “We need to be able to learn from the agility of these young companies.”

Seed businesses need more hand holding

Young businesses are so early in their development that they often need help with basic business building such as hiring and support with product changes. The venture team needs to have the skills to support early-stage companies. First-time founders, in particular, will need more support than more seasoned entrepreneurs. “It is very important to be close with the founders and to establish a good setup for the company because it makes everything later on much easier,” says Haidl.

Expect early-stage businesses to fail more frequently

Around 50% of seed businesses will not survive long term, Wang estimates. Corporates need to be aware of this and understand investments are higher risk. It is easier to assess a company at series A because the management team is more mature and it is often clearer what the market fit is for the technology.

Investors in seed companies should set expectations with the parent companies that early-stage businesses have a higher failure rate and need to be managed differently. Haidl says his firm often plays a mediator role in early-stage investments because companies often think “all you need is structure and a development path and then the company will be successful. It is completely different to how early-stage investing works. We often try to repeat this in board meetings and shareholder meetings, so that they understand it’s not managed like a later stage company.”

Be careful not to dissuade founders with contract terms

The quality of the team is everything in seed investments. Overbearing funding terms, such as asking for majority ownership of the intellectual property and rights of first refusal, can kill seed investments early. Founders are disincentivised if they feel they will lose control of their IP. Haidl says university spinout founders still have a hard time because of corporates wanting to put in place terms, such as purchase options, that they see as excessive. This can also happen in corporate spinouts. “The parent will often say we want 60% of the company. And then it is really hard to incentivise a management team for the long term,” says Haidl.