Rounds are getting bigger and investors want to see more earlier, but the distinction between them is still important.

“ The goalposts for series A used to be a million dollars in revenue, and now it’s more like two to three,” says Elizabeth McCluskey, managing director at TruStage Ventures – the corporate VC unit for insurance provider TruStage – and head of its early-stage Discovery Fund.

“I think it’s more likely these days to see companies raising seed rounds that are at or approaching a million.”

The boundary of where a startup funding round is called seed-stage and where it qualifies as series A is getting blurrier. There has always been some grey area in the definition of fundraising rounds – is an $80m series C startup that much less mature than one raising a $50m series D? But at the early stages, when companies are just figuring out their market and the risk is higher, the perceived borders are more consequential.

“Every time I talk to a new investor, we always kind of compare notes on what we mean by seed, because if somebody says they’re a seed investor, I still do think that can mean different things. Some people still have an older definition, and then some people have the newer definition,” says McCluskey.

TruStage Ventures’ discovery fund backs pre-seed, seed and series A startups, particularly those with underrepresented founders. Currently, it has around 20 startups in its portfolio.

Longer time between rounds

It’s not just the size of the rounds that is changing, but also the time between them. It used to be common to see companies moving to a new fundraising round stage every 12-18 months, but those timelines are spreading to around two years between seed and series A, then maybe another 2-2.5 years between subsequent rounds after that.

“Every time I talk to a new investor, we always kind of compare notes on what we mean by seed.”

Elizabeth McCluskey, TruStage Ventures

“A lot of companies who raised what were previously considered seed rounds, but then weren’t at that $2-3m revenue rate to be able to raise a series A kind of got caught in the middle,” says McCluskey.

Partly as a result there has been a spike in post-seed rounds, seed extension rounds and pre-series A rounds. There is also increasing use of insider bridge rounds and simple agreement for future equity —or SAFE — notes. These financial instruments tap existing investors for more funding rather than bringing in new investors, which would trigger the move to the next investment stage and a new valuation.

One thing that hasn’t changed much at seed stage is the size of the startup team size itself. Even though seed stage companies are expected to show higher revenue than before, they are still expected to be run by a small crew. There’s a heavy focus on capital efficiency and reducing cash burn in the current market, so investors want to see smaller teams, if anything.

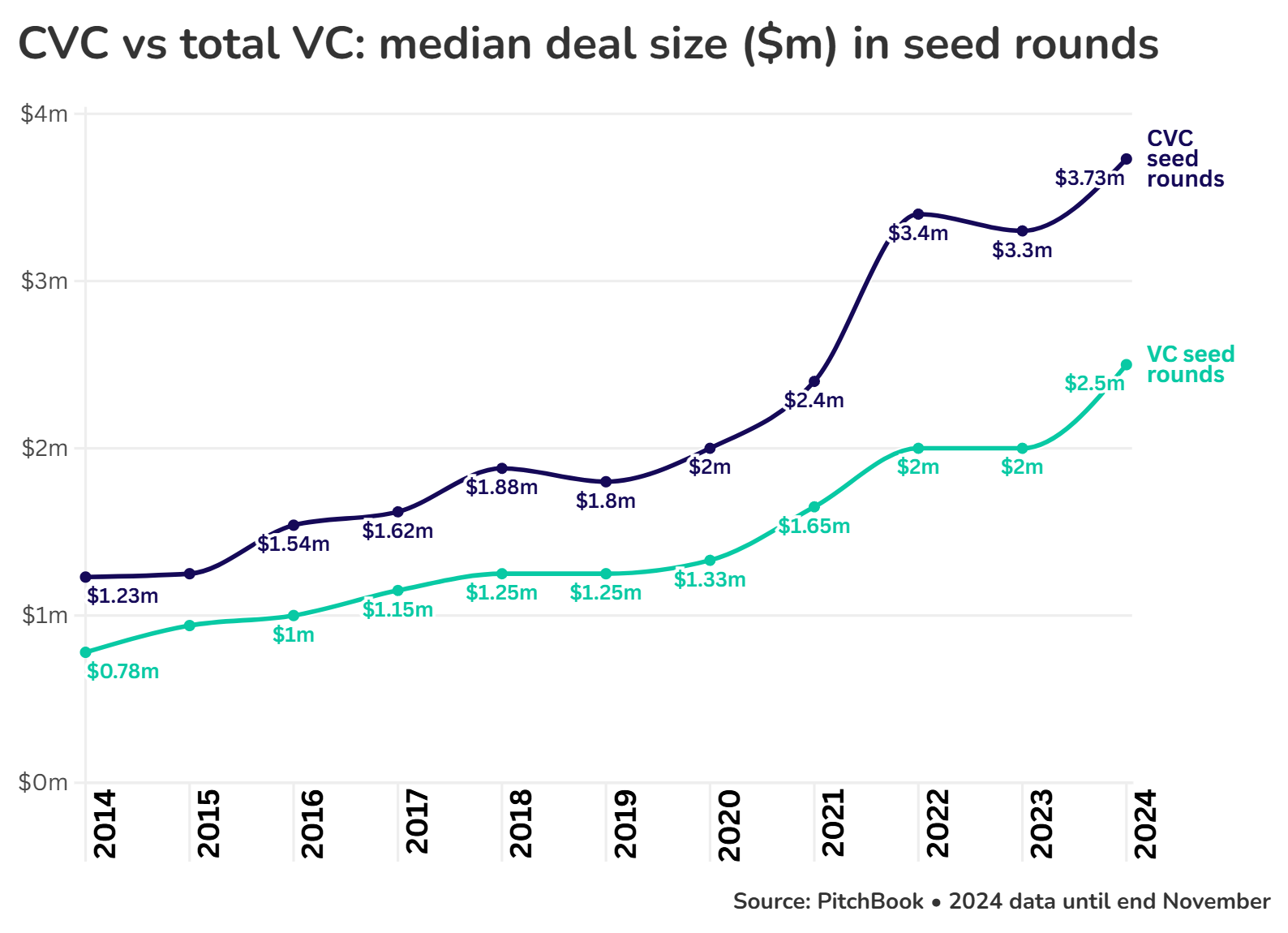

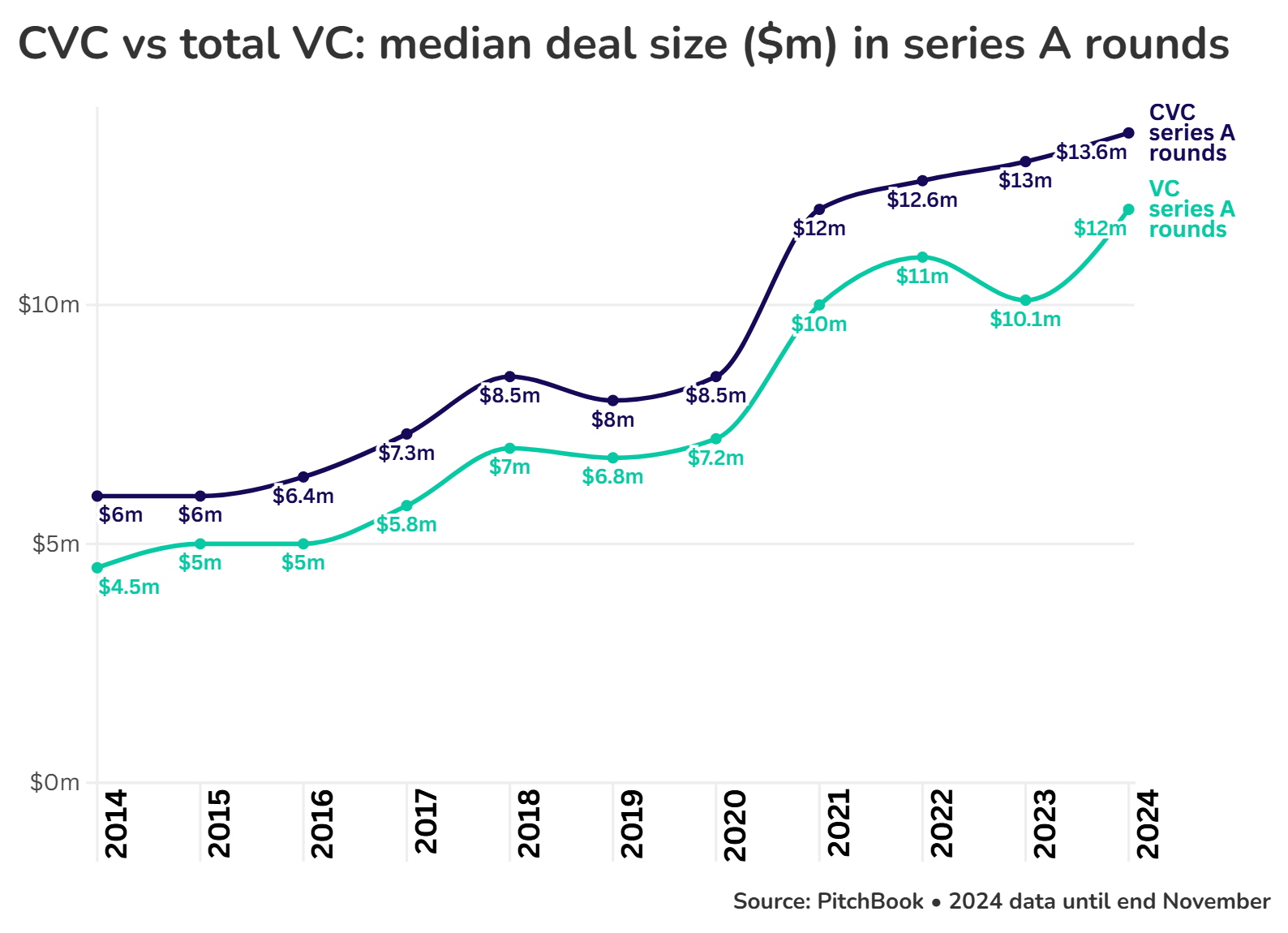

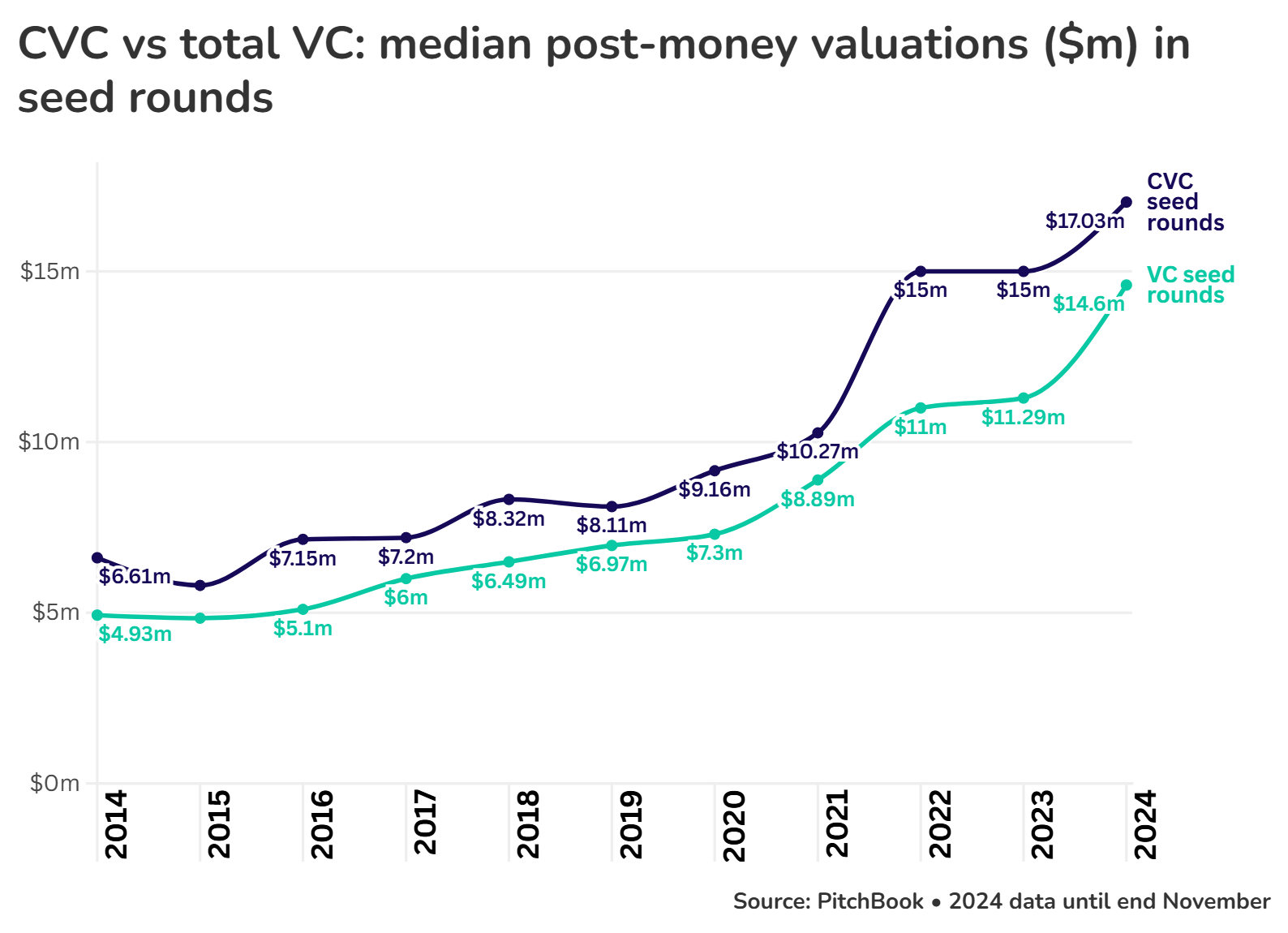

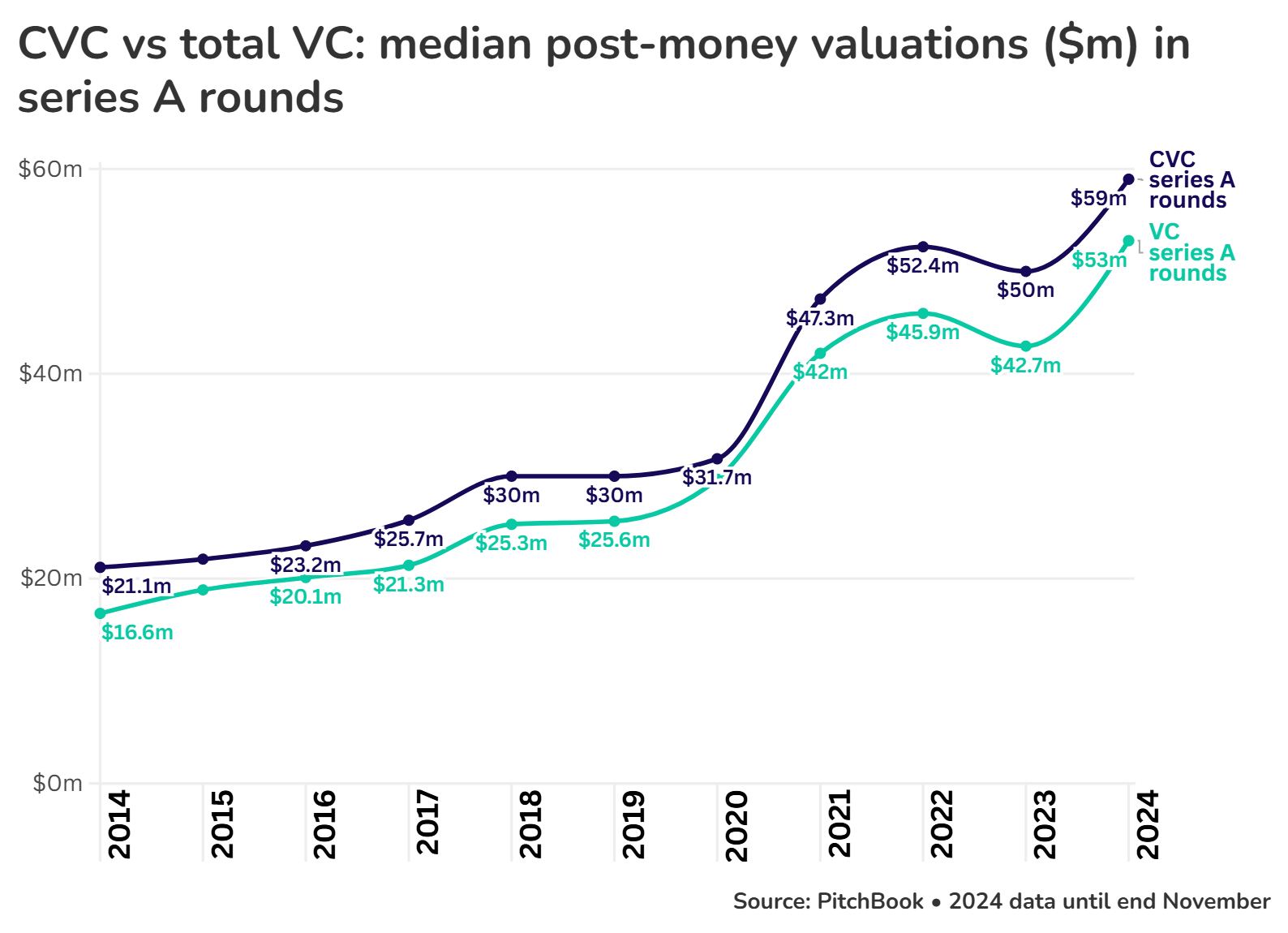

Median deal sizes for seed rounds have nearly doubled since 2020, with the same being roughly true for series A rounds, according to PitchBook data. The trends for median post-money valuations are also up since 2020, though not to the same extent.

Notably, neither median deal size or post-money valuations for either seed or series A rounds seem to have suffered much in the venture downturn beginning in 2022 — certainly nowhere near the level of decline seen in later rounds. All those measures are currently at all-time highs — while measures for later rounds have yet to reach previous levels.

Earlier milestones and later exits

Startups are also feeling pressure to show signs of de-risking earlier as investors want to see paths of success sooner. Seed-stage companies are expected to have a stronger sense of go-to-market strategy and product-market fit than they used to.

At the same time, pre-seed investors have become harder for companies to find. Even angel investors, for whom pre-seed and seed have historically been the bread and butter, have been shifting into syndicates backing later-stage, less risky startups.

“Funds are looking for shorter timelines to exit for any new investments they’re making. So they’re definitely not going to go to the earliest pre-seed companies who are going to probably be 12-plus years to see an exit,” says McCluskey

This is a sentiment echoed by Peter van Gelderen, general partner at Icos Capital – a VC focused on food systems, decarbonisation, and chemicals and materials – who in recent years decided that the seed stage was not worth the hassle, and has since been focused on series A at the earliest.

“ You can invest one year later [when the company is at a more mature stage] – it doesn’t do much to the valuation and improves the risk profile a lot. And in some cases, we found that, after three years, these [seed-stage] companies are still going in rounds and not ready to scale,” he says

“People are over optimistic in the good times and they’re also over pessimistic in the bad times.”

Peter van Gelderen, Icos Capital

“For us, it was simply taking too long. In our first fund, we still have two companies that are in year 16 and in year 12. That’s the reality of these businesses. So we said, okay, that is simply too long – we cannot go back to our investors for 12 years and say, everything’s going to be fine. They want to see results after five, six, seven years.”

The hope is that as the exits come back, fund managers will start seeing returns which will hopefully be recycled back and trickle down to the earlier stages.

CVCs vs VCs

Seed-stage companies do have more of a champion in corporate-backed VCs. Everyone wants a good return, but CVCs’ strategic angle makes it more worth it for them to venture earlier relative to financial VCs and take a risk with the hope of bringing something useful to the corporate.

Mirroring that, the fact that they can rely on the corporate value-add gives more confidence that they can help younger startups reach the next milestone.

The strategic focus, and on-balance sheet or evergreen structures also tend to make CVCs’ capital more patient than a fund manager who needs to look for the exit 7-10 years down the line.

“People are over optimistic in the good times and they’re also over pessimistic in the bad times. I still think there are good things out there to invest in, but you have to be very, very cash conscious, because I always say every euro or every dollar you take from an investor, you have to first earn back three times before you start making money as a founder,” says van Gelderen.

Is the seed-series A distinction still worth making?

There has never been a hard and fast rule about where the boundaries between funding rounds are, in dollars or otherwise, so labels can still be useful, says McCluskey.

“I think [labelling rounds] is mostly useful as a sorting mechanism and for communication. We are known as a seed stage fund, or we are known as a series A fund, to help the market think about you when it comes to certain deals,” she says.

“From a first-principles perspective on execution and who you want to support, especially at the seed stage, it’s still so much about the founder versus the numbers. I think at series A, there are more rules that you don’t want to break. In seed, everything’s a little bit softer around the edges in terms of what counts and what doesn’t.”

Fernando Moncada Rivera

Fernando Moncada Rivera is a reporter at Global Corporate Venturing and also host of the CVC Unplugged podcast.