Space exploration is driven by commercially focused startups rather than just the defence industries, opening up a power shift.

It was Peter Thiel who, in a chat after his lecture at the University of Oxford in the late 2000s, told me that space would be the next big investment opportunity — a chance to leverage what had then been 50 years of state spending.

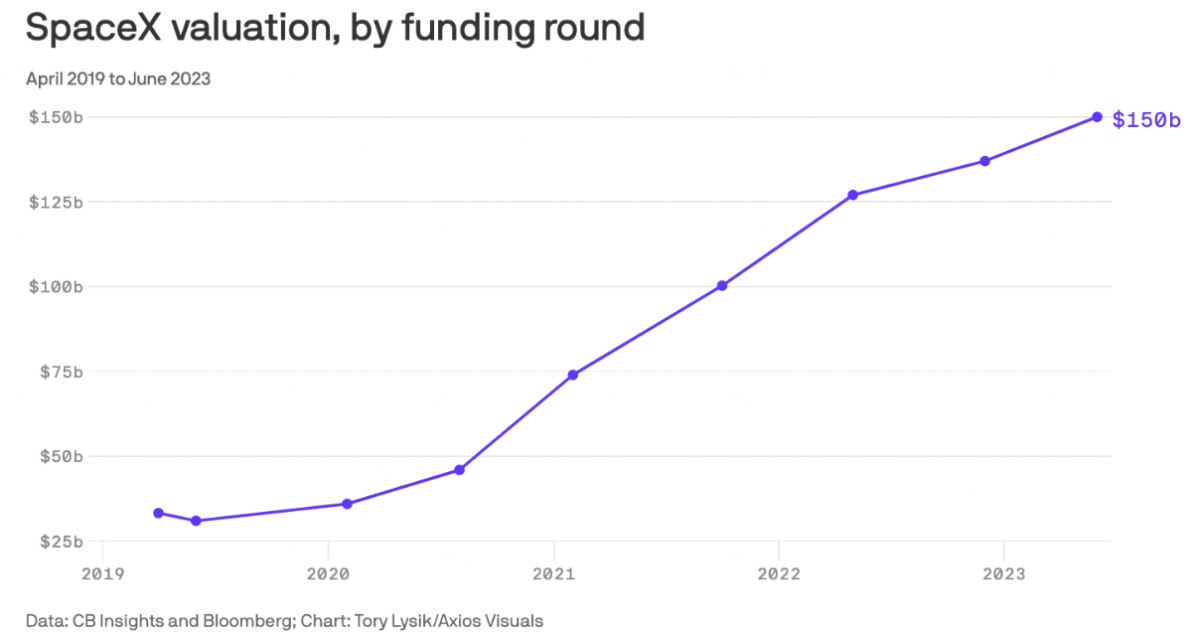

Fifteen years or so on and it has indeed been a lucrative bet. Thiel has helped fund SpaceX – now reportedly a $150bn company – as well as a host of space-related companies including Palantir, Anduril, Varda Space Industries and Impulse Space Propulsion.

These companies are all capitalising on two trends: large cost reductions to take payloads into orbit and miniaturisation of electronics, which is opening up new software and data streams beyond Earth.

“Elon [Musk, founder of SpaceX,] came in and removed the bottleneck of Russia-dominated launches with a cheaper and faster method. Now, we can get infrastructure into space with a 95% drop in cost. Together with the miniaturisation of electronics with software-defined upgrades the backbone technology is more efficient – cheaper, better, faster,” says Bogdan Gogulan, CEO of growth equity firm NewSpace Capital.

Now, he says, investment focus is shifting away from launch to applications that make use of space infrastructure.

“Still, however, 58% of the $240bn or so invested in early-stage space-related companies over the past 14 years has gone to launch even though it is only 1.5% or so of this industry’s revenues. I call this the ‘Musk’ effect in an era of cheap and abundant capital,” Gogulan says. “Now, growth will be demand-driven to use space to make productivity gains in traditional industries, such as better application of fertiliser in agriculture or better mining projects or insurance. Space is a place not an industry.”

Together, these trends are allowing startups to compete against the state-funded military-industrial that has dominated space since the first rockets were launched.

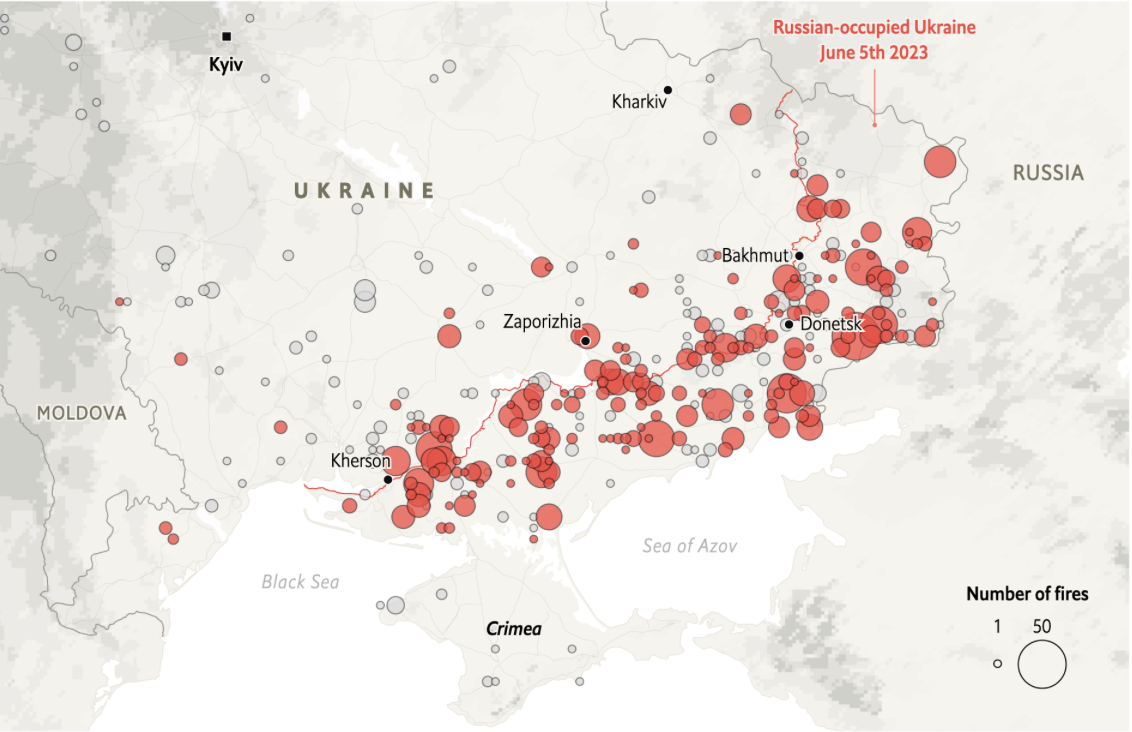

The head of one national space force, talking under the Chatham House rule, said startups could be part of the deterrent policies being drawn up. We have entered a “second space age” and a good example is Ukraine’s use of Musk’s Starlink satellite constellation to maintain communications in the early days of Russia’s invasion, after missiles and cyberwarfare had taken out Viasat and other communications. Building resilient constellations of satellites and data transfers was his priority and his primary method of achieving this was to change the procurement policy to enable more use of commercial operators by the government agencies.

Daniel Ateya and Kyle Perez at RTX Ventures, the corporate venturing unit of US defence company Raytheon, said three segments of spacetech are of most interest for entrepreneurs: satellite communications, geospatial intelligence and earth observation, as well as positional and navigation technology (PNT).

“These three segments have relevance for commercial and defence industries from satellite advances and serve world needs with the dramatic increase in data transfers, for example the war in Ukraine by Earth observation. It is eye-opening what imaging can do and this can be applied to business and military operations,” said Ateya.

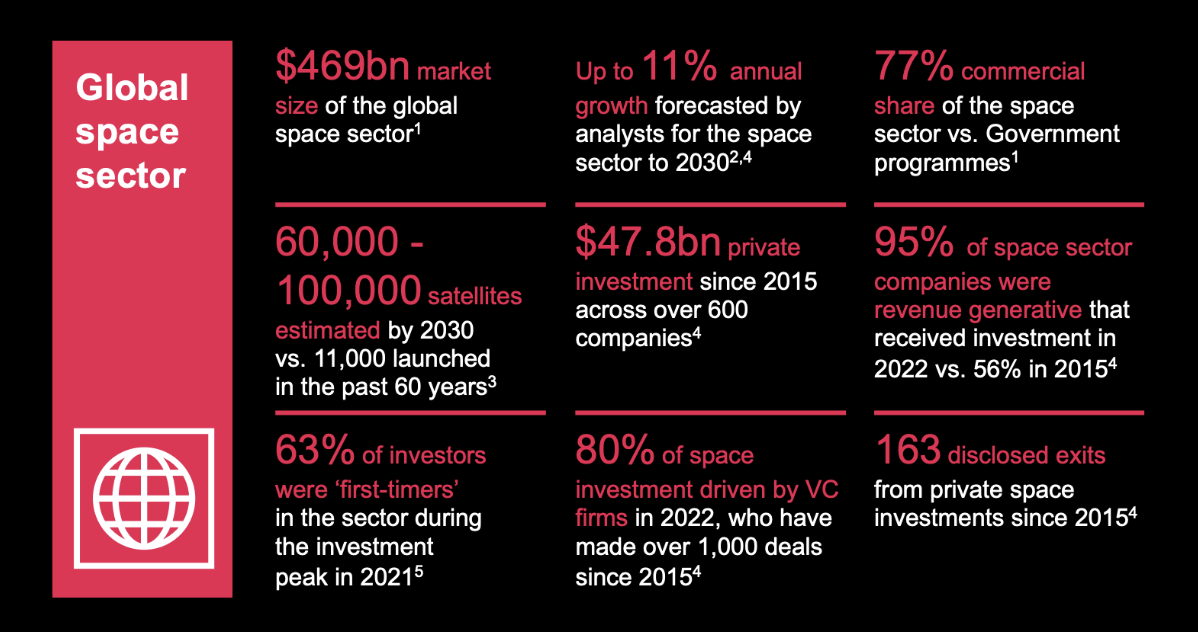

The space tech market is expected to grow at an 11% a year rate, reaching $321bn by 2025, according to data provider Pitchbook. The primary opportunity remains in the terrestrial and orbital segments, the Pitchbook team says.

RELATED STORY: 11 space tech startup to watch

“Exploratory technology remains a distant dream, although some recent advances, such as in-situ resource utilisation on Mars, suggest that the intermediate steps to make a truly space-faring civilisation could present a near-term investment opportunity,” said Ali Javaheri, associate analyst for emerging technology at Pitchbook.

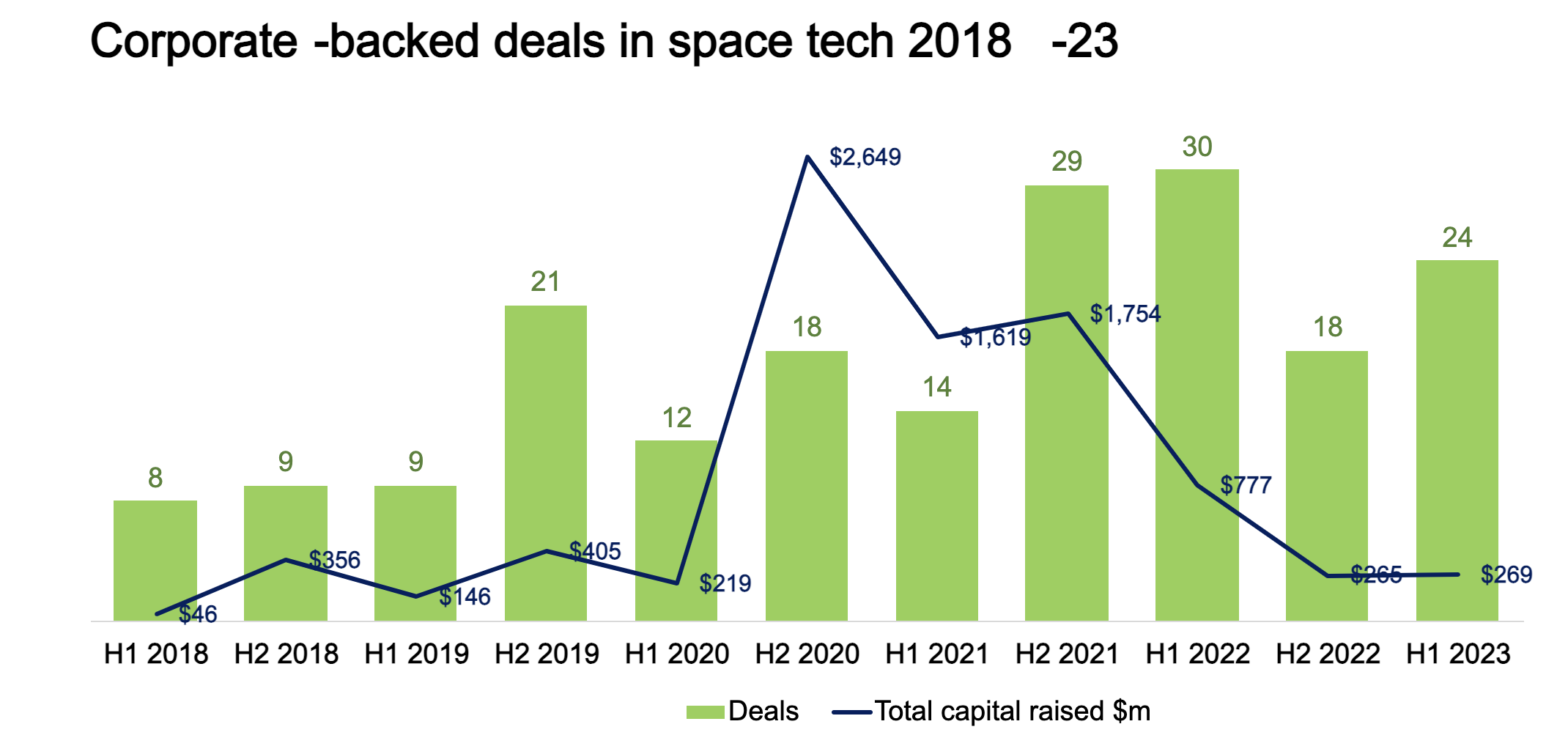

Outside of a handful of VC investors such as Thiel’s Founders Fund, Seraphim, NewSpace, it is strategic investors, such as Airbus, In-Q-Tel and Lockheed Martin, that dominate spacetech investing. They are behind the dozens of deals each year in spacetech, according to Pitchbook, with PwC analysis on behalf of the UK Space Agency indicating almost two-thirds of investment came from non-aerospace and defence companies.

One is example of the way that new spacetech is being used is the system the Economist developed to track the fighting in Ukraine. It took data from Firms, a publicly available system set up by US’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa), which was originally designed to detect forest fires from satellites flying over the world twice a day. The Economist built a machine-learning algorithm that evaluates the location of each fire detected by Firms and assesses whether or not it is related to the war.

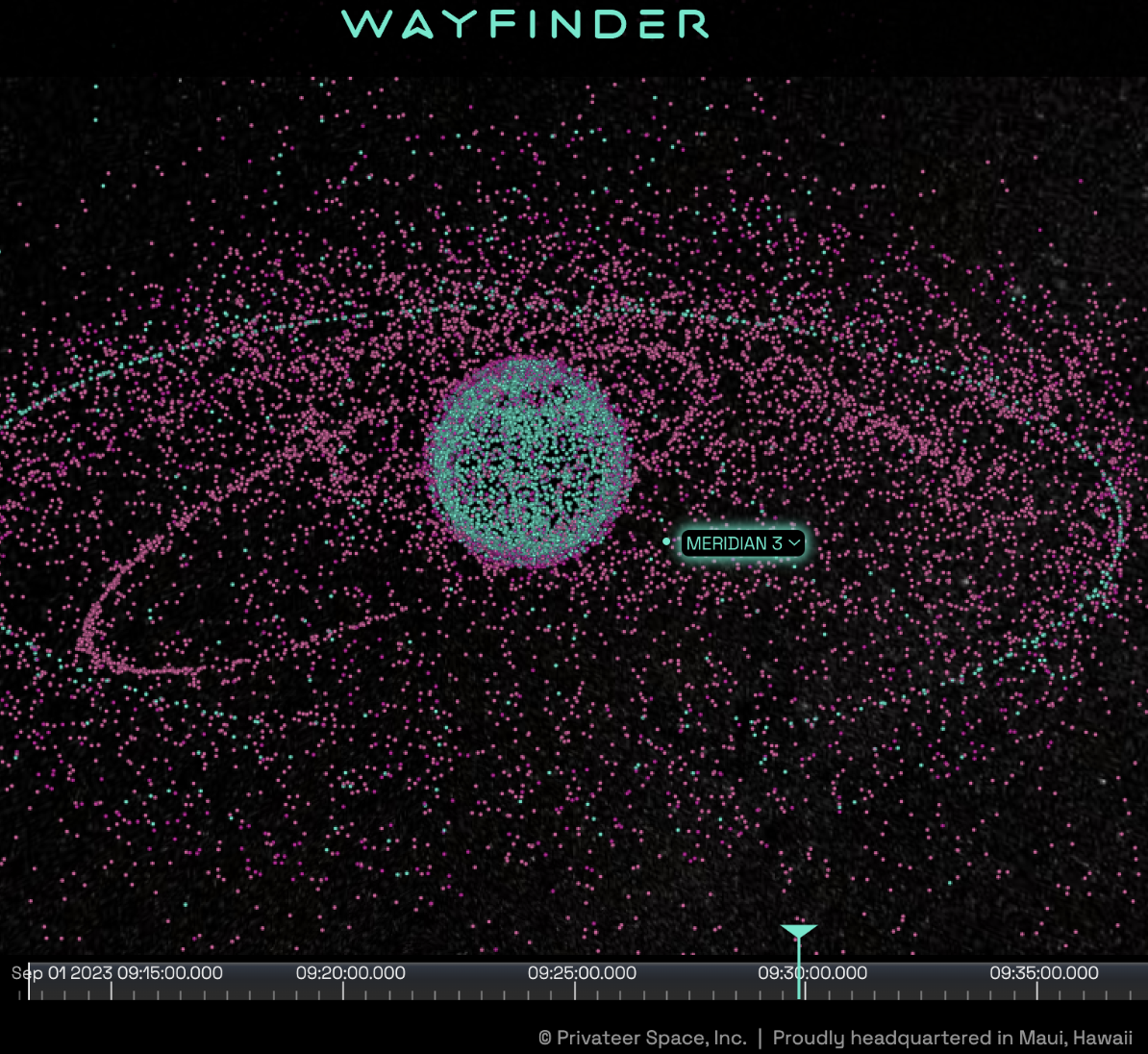

Most of the satellites like this are now commercially owned and even the spy satellites from Russia and other countries can be tracked by publicly available sites, such as Privateer, creating an ever-changing map of what space experts, such as Bleddyn Bowen, lecturer in international relations at the University of Leicester, calls the space littoral of Earth.

This map could look increasingly crowded as some experts expect there to be 60,000 to 100,000 satellites in orbit by 2030.

Satellite data can not only be used to analyse fires, but startups, like Tomorrow.io, backed by RTX, are using it to better predict weather patterns or look at the after-effects of extreme weather for insurers. This is already disrupting incumbents. The next step will be tackling new horizons, such as cis-lunar space — the area of space inside the moon’s orbit — or asteroid mining. A foothold in these areas of space would project space power for companies and countries in much the same way that, as naval historian Andrew Lambert notes, trading posts along the sea lanes on Earth brought commercial and military benefits to 17th century seapowers such as the UK and Netherlands.

Mark Boggett, CEO at UK-listed Seraphim, the most active VC firm in spacetech with more than 100 startup investments, says analysis of sea power development was analogous to space power. “The space race is on now. Defence and intelligence was the first rung then quickly opened to climate and sustainability and telecoms as it is a horizontal technology like AI [artificial intelligence] that we use every day without often noticing it.”

Rob Desborough, managing partner at Seraphim, added that a tipping point has been reached where a defence department — while it could be a customer — was no longer big enough by itself to scale a VC-backed space tech business. Space tech is moving into an era of managing infrastructure, such as refuelling satellites, and into the logistics and manufacturing of new products, taking advantage of zero gravity to do work on cells and monoclonal antibodies that would be impossible on Earth.

Cvic Innocent, former Nasa scientist and now a board member of VC firm Erez Capital, says countries with vibrant startup ecosystems active in space will create better opportunities, but, just like the development of maritime democracy over the past 200 years, the space economy needs to avoid becoming a lawless environment.

It is not just the large military powers like the US and China vying for a foothold in space. Last month, India was the first to land a space rover on the south side of the moon, where there is potentially frozen water. Space exploration will bring opportunities for all countries to redraw power lines.

GCV will be holding a roundtable on spacetech later this month before a meeting of the Global Defence Council and Global Mobility Council of strategic investors is held in New York City on 13 October as part of GCV’s Executive Leadership Forum – register here.