It is hard for newcomers to compete in the automotive semiconductor and software market but there are a few niches in which small companies can make their mark.

When you buy a new BMW these days, you are sure to be impressed by the augmented reality graphics inside the car. Real-time information about your surroundings, such as potential collisions and navigation instructions, are displayed either on the windscreen or on the dashboard.

The AR graphics are there to improve driver safety and ease the transition to semi-autonomous driving. Finnish late-stage startup Basemark makes the augmented reality software that is built into operating systems and runs on chips inside the car. The company has cornered the market in augmented reality software for the automotive market with its unique blend of expertise in computer vision, artificial intelligence and graphics. It also has intimate knowledge of automotive processors on the market, having performance-tested them for various semiconductor clients. This helps it understand processor capabilities and how to run its software efficiently.

Basemark’s commercial success is unusual. It is notoriously difficult for startups to compete in the automotive semiconductor and software markets. One reason is the large amounts of money needed to the make products such as powerful processors for advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), and the long lead times for getting the products into cars.

This is the reason that large tech companies like Nvidia, Mobileye and Qualcomm that have large financial resources and large teams of experts have dominated the sector for ADAS processors.

Any startup has a long road to get adopted and deployed in the automotive industry. This is particularly true for something as important as semiconductors.”

Tony Cannestra, director of corproate ventures, Denso

Tony Cannestra, director of corporate ventures at Denso, the Japanese auto parts supplier, says the wave of automotive chip startups set up between six and eight years ago have struggled to compete with the large players that have put a lot of investment into automotive market for chips, having realised the large growth potential for the sector over the next 25 years.

“The startups from that initial wave have struggled to make market penetration. We have seen that with lidar and radar companies as well,” says Cannestra. “Any startup has a long road to get adopted and deployed in the automotive industry. This is particularly true for something as important as semiconductors.”

But pockets of the market do exist for startups to make their mark. Basemark captured an area of the automotive software market that is large and growing quickly but also involves complex technology and is fragmented. “There are segments where you don’t have so much competition and where specialists are needed,” says Tero Sarkkinen, founder and CEO of Basemark. “We have found such a segment with augmented reality application, where you need to master graphics, computer vision, neural networks and machine learning.”

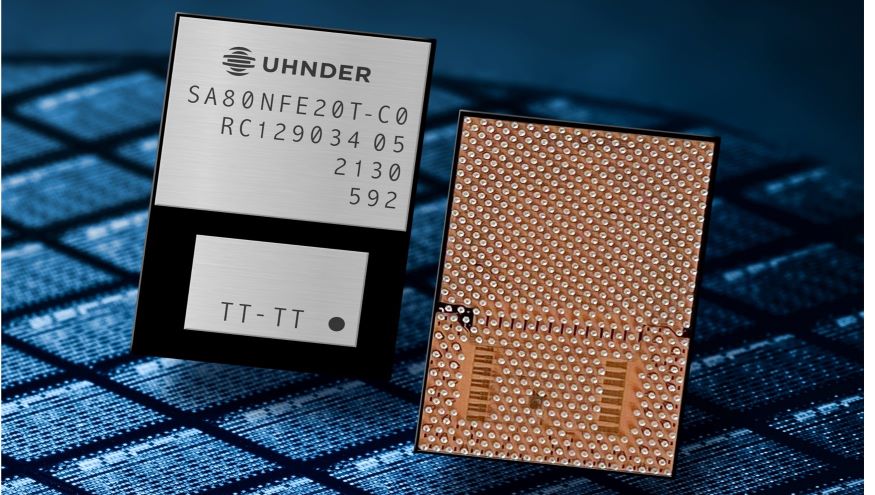

Another mature startup that has carved out a market niche is Uhnder, a US-based maker of digital imaging radar. The technology, which is integrated into silicon-based chips inside the car, works similar to lidar in that it detects surrounding objects to avoid collisions.

Traditional radar has performed poorly in advanced driver assistance systems because it interferes with other radar. But converting analogue radar into digital has resulted in better detection in bad weather and at high speed, says Manju Hegde, co-founder and CEO.

A benefit to radar is that it is a well-known technology that car suppliers are well accustomed to, says Hegde. “Lidar is a new technology, so everyone talks about it. Bur radar is an established technology. OEMs are comfortable with it.”

Uhnder has raised $145m from corporate and financial venture capital investors. Corporate investors include automotive supplier Magna International, US tech company SAIC and TDK Ventures.

The biggest challenge facing the company is the slowness of auto suppliers to deploy new technologies, which can take several years. It is also costly. “We are always fundraising,” says Hegde. “Semiconductors are one of the most capital-intensive technologies.”

Sarkkinen at Basemark says he faces similar challenges operating in the conservative auto supplier sector. “It takes two to three years to pitch a company,” he says. “Then you are in a deal supporting them during their development phase, which could be four years. At the end of four years, they start to produce the vehicles, and then a seven-year production cycle begins.”

Basemark has raised €15m ($16.5m) so far and is closing a €10m round. It counts an undisclosed corporate investor in its latest capital raise. UK VC firm ETF Partners and Finnish Industry Investment, the country’s sovereign wealth fund, are also investors.

Amit Shofar, investment director at Samsung Catalyst Fund, an investment arm of the Korean conglomerate, sees opportunities for startups in areas such as in-vehicle networking where vehicles communicate with each other to avoid crashes.

“There are areas of the automotive semiconductor market that are less in the spotlight, where we see innovation and room for start-ups to shine and capture sizeable market share, for example, communication and in-vehicle networking. The new automotive architecture requires multi-gigabit networking to connect all sensors with the main processors as well as for the 4G/5G connectivity with the cloud. Multiple emerging companies are trying to address that,” says Shofar.

The fund invested in Valens, a maker of automotive semiconductor products, which is now listed on the New York Stock Exchange. It also invests in Autotalks, a developer of a chipset that enables drivers to know about dangers that are out of the line of sight.

“We now see the emergence of startups developing solutions for the core network of the car, an interesting domain that could become a sizeable market,” says Shofar.

Other early-stage startups specialising in this area include US startups Aviva Links, Axonne and Ethernovia, which develop in-car networking technology for advanced driver-assistance systems.

The power required to mimic human brain

For autonomous vehicles, finding the right amount of raw compute power – how many operations per second that a chip can perform – is the holy grail of automotive semiconductor manufacturing.

“We are looking for more raw compute power, with lower power consumption, and with as little latency as possible,” says Cannestra. “If you are a semiconductor company, the ultimate goal would be to deliver a product that somewhat mimics how the human brain rapidly processes information to make complicated decisions. For vehicles to drive autonomously, they will need compute power to make complex and intricate decisions very quickly.”

China has put a lot of investment in automotive semiconductor sector after falling behind in the design of cutting-edge chips. Active Chinese corporate investors include GAC Capital and SAIC Capital China. The US has tried to boost its own domestic market with the passage of the CHIPS Act, which funds the onshoring of chip manufacturing as well as startups.

Government support is well needed as the costs of becoming a semiconductor maker have ballooned since the days when the likes of Nvidia and Intel were startups. For one, the cost of manufacturing ever smaller chips has become more costly.

“Everything is fabless but it is more expensive to become a chip company from inception to exit. You might be looking at hundreds of millions of dollars to make that happen. The investor appetite for that has diminished in the US and Europe,” says Cannestra.

The turmoil in the financial system is also taking its toll on startups trying to raise funds.

Tough market for startups

“It is a horrible situation,” says Sarkkinnen of the challenge of raising capital. “Even very good companies with solid business plans are really struggling to get funding and then at an acceptable valuation. A percentage of companies are going into financial distress. They have to get funding at any terms. This leads some predatory investors to wait and see until they can get pennies on the dollar investments done.”

The less predatory investors are also more cautious about investing because they are unsure whether valuations will continue to drop. “Nobody wants to do investments now because they think that six months from now it can be said that they made an investment at too high a valuation,” says Sarkkinnen.

Despite the market conditions, Basemark continues to attract investors. The company kept its most recent round open for longer to allow for more investors that have shown interest.

For startups that can get a foot in the door with auto suppliers, the scope for success is too large to ignore. The automotive augmented reality market alone that Basemark specialises in is predicted to grow to $15bn by 2028 from $4bn today. “We aim to become one of the leading software suppliers in the automotive market. It will take time, but there is huge opportunity,” says Sarkkinen.