Turkey has the ingredients to be a top tech market, but it needs investors to take more risk if its startups are to get past early stage.

Turkey has a bigger population than any country in Europe, strong universities and a relatively well-trained workforce as well as an economy that outstrips tech powerhouses such as Switzerland or Israel. But with all these advantages, why is it lagging behind in venture funding?

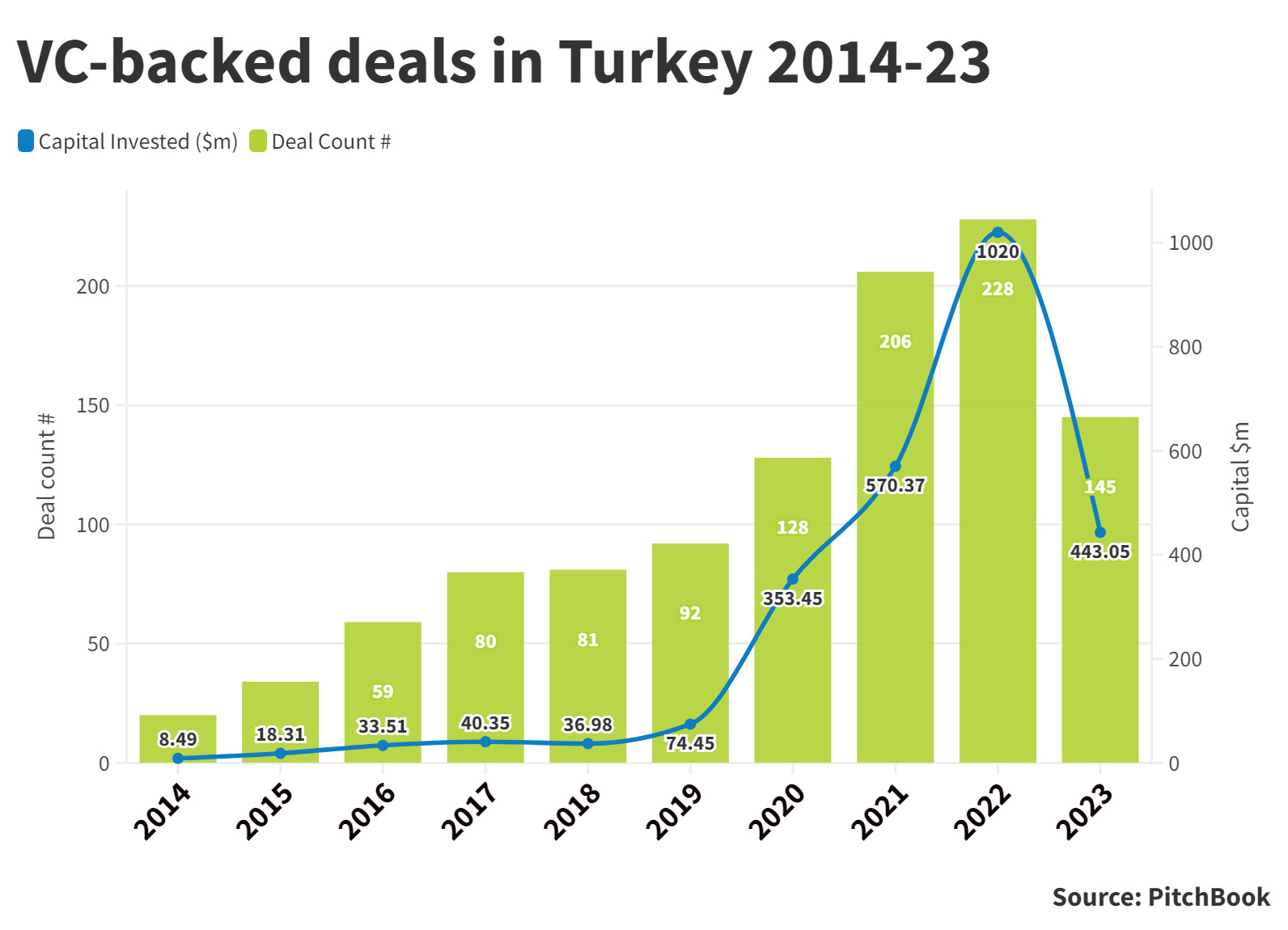

Funding for Turkish startups has increased in recent years and topped $1bn last year, but while corporates are active, the actual deal amounts remain small and the country was outside the top 30 for cash raised in VC-backed rounds, below the likes of Colombia and Austria.

In theory, corporate venture capital could make a big difference. Some 80 corporations in Turkey have now created investment arms, with the most prominent including petroleum supplier Tupras, conglomerate Alarko and construction firm Tefken. However, as they often can’t find the startups they want at home, they tend to frequently invest in other markets.

Turkey has plenty of startup advantages, but funding remains scarce

“Turkey is a young population,” says İhsan Elgin, executive board member at Finberg, the venture capital subsidiary of Turkish bank Fibabanka. Founded in 2018, the investment unit has backed startups including grocery delivery startup Getir and ecommerce company Easycep.

“Right now, there are almost 100 million people and 50% of this population is under 30. Turkey has unbelievable university numbers and the most powerful programmes in the university are engineering, so we have lots of engineers.”

The country has more than 200 universities in total and investors agree the academic base is strong. The barrier comes with commercialisation. Many talented academics are reluctant to take the risk to launch a startup, and investors are often unwilling to take risks at the point where funding is required to build out a technology product.

“The connection between universities and the business world is very weak because many universities have R&D centres, but they don’t have enough money and resource to support entrepreneurs,” says Gaye Ör, partnership coordinator at Finberg.

Investment is the largest hurdle for universities, agrees Mahmut Ozdemir, director of KWorks, the accelerator and entrepreneurship research centre linked to Koç University. You can launch a startup, but it becomes difficult to grow past a certain point because the capital is just not there.

“We have angel investors and angel investment networks that are doing pre-seed and seed rounds,” says Ozdemir. “Then, we have pure series A investors as well, but once we move to series B, C or D we have a problem because these are difficult for Turkish startups and investors.

“If your valuation exceeds $50m, you will face difficulties in finding an investor in Turkey”

“If your valuation exceeds $50m, you will face difficulties in finding an investor in Turkey. You need to go abroad or slow down growth. We still have this problem, and we’ve had it in Turkey for many years – capital has not accumulated in a way that very rich organisations or people can invest in startups in huge amounts.”

Investors, on the other hand, say it is hard to find larger startups. İlknur İlkyaz Gül is general manager of Driventure, the CVC arm of Turkey’s largest automotive manufacturer, Ford Otosan. The unit has participated in rounds in Turkey and abroad, and it is interested in finding mobility startups at scale-up stage. The problem is once you get to a certain point, she says, there aren’t any.

“We are aware that it is riskier to invest in early stage, but crucial for the development of the ecosystem,” Gül says. “We are also aiming to increase our ticket sizes and invest in later-stage startups, but we couldn’t find scaled startups.

“Therefore, there is a dilemma on whether to invest at early stage and take more risk, or wait for a later stage like series B, C or D, and struggle to find both scaled startups and the right ticket size.”

What many Turkish investors like Driventure end up doing is looking abroad for larger deals. However Driventure’s relatively small spend per deal – typically $50,000 to $500,000 – means the pool of international startups it can back is also small.

The Turkish government has attempted to boost the environment for early-stage tech companies in recent years. There are tax incentives for corporates to invest in Turkish startups, mandates for asset managers to do the same and initiatives like the 1507 Tübitak scheme, which provides grants to support startups’ research and development work. But the issue is similar: support is strong at early stage but dissipates later on.

VC firms generally go up to series B and private equity firms contribute at series C and D-stage, but one thing everyone agrees on is that there aren’t enough investors or enough capital to go around. Some international firms have begun to dip a toe in the Turkish startup scene, but they are often from similarly undeveloped markets in regions like the Middle East.

The question remains: just how much of the investment gap might Turkey’s CVCs be able to fill?

The role of corporate investors in Turkey

Banks, which are some of largest businesses in Turkey, are also some of the country’s most active corporate investors. Finberg, for example, has invested in or partnered with more than 40 startups.

“Banks are playing an important role because they were almost the first companies that noticed the importance of being closer to the startup ecosystem,” says Ör. “That’s why they built CVC funds.

Financial services firms are looking at the startups they back as not just investments but future customers. “Banks are actually trying to reach new customers all the time, and small startups are ideal for them. They don’t waste lots of money,” says Ör.

The other industry with a particularly large presence in Turkey is telecoms. Türk Telekom and Turkcell have 64 million mobile subscribers between them and have both begun investing locally, generally splitting their deals between high-tech seed-stage startups and developers of consumer apps that can be integrated into their overall offering.

A strong showing in IT and a lack of funding for growth-stage hard tech means Turkey’s biggest startup success stories have been in the consumer sector – either in casual gaming, where Dream Games, Loop and Spyke have notched up large valuations, or in ecommerce, where on-demand grocery provider Getir and digital marketing company Insider have reached unicorn status.

The dilemma of internationalism

Elgin suggests the country’s location, less than four hours from London or Dubai, is a strong factor for consumer technology along with its culturally diverse population.

“We have British people living in Turkey in the seaside areas, the Russians and Ukrainians, and right now, we have lots of Arabic people from Qatar and now Syria. So, whatever you try, if you’re successful in Turkey, it means you can be successful regionally from the UK to Dubai, because it’s a really good testbed and example population but it’s not a small population.

“Take Getir,” he adds. “They were successful in Turkey first and they started in Europe and the UK very easily, because we have all the cultures.”

Getir and Insider may have been formed in Turkey but both are now based overseas, which plays into one of the country’s largest problems. The lower cost of living and high domestic inflation means many of the most skilled digital workers can make more money moving elsewhere or being employed remotely by foreign businesses.

“Many talented people who live in Turkey are finding better opportunities abroad, and that is difficult,” says Ozdemir. But there are advantages for local startups, he adds.

“One of the models today is that business development teams for startups or co-founders relocate themselves to Europe, the UK or the United States and leave their technical teams in Turkey, develop products here and then sell them abroad.

“This is a working model where they can receive foreign investment and get foreign customers, so some of our alumni startups that graduated four or five years ago have started making revenue in dollars or euros selling to customers outside Turkey.”

Getir is one of these companies, Ör says. They have relocated sales and management to the UK while keeping their core operations local. A related issue is that Turkey’s less advanced digital economy means startups need to expand internationally early Elgin adds, but the country’s size as a whole can make it tempting to simply stay local and get a mid-sized return, instead of competing on a larger scale.

The solution is that Turkish startups must think on an international level from day one, he says. Founders have good ideas, and when you combine that with demographics that make the country an ideal proof-of-concept market, it is a great place to launch a company. But the reason it is yet to become an attractive market on a global scale isn’t a lack of talented founders.

“The reason is their mindset,” Elgin says. “Because they think it’s enough.

“They can make so much money, but they never focus on making a billion-dollar company. Of course, Getir and Insider are different examples, but I’m talking about the bigger group. They say $100m is enough; in Turkey, we have $50m, $100m exits but they always focus on that idea. This amount, this ticket size is not enough for international investors.”