Researchers or investors could face jail terms if they work with someone they “ought to know” is under the direction of a foreign power.

Investors, universities and research and development departments are facing a new legal headache as the UK government drafts them into the fight against foreign espionage and intellectual property theft. Anyone working with a “foreign power”, or an entity controlled by one, may be required to log the work with the government, with criminal penalties for non-compliance.

Individual researchers or investors could face jail terms if they work with someone they “ought to know” is under the direction of a foreign power, or neglect to record their work with a public registry.

The UK government’s National Security Bill had its first reading in the House of Commons on the 11th of May, and could be passed into law in the coming year. In an article published in The Daily Telegraph that day, Home Secretary Priti Patel stated that the Bill’s aim is to curb “hostile foreign activity” directed by states such China and Russia.

In its current form, the Bill will criminalise a variety of activities conducted by, for or in collaboration with “foreign powers”. A Home Office media release describes it as the “biggest overhaul of state threats legislation for a generation.”

Some new offences proposed relate to “obtaining or disclosing trade secrets” and are intended to bolster the UK’s protection from intellectual property theft. Others relate to “general” foreign interference activities, which may increase the risks in dealing with actors from countries such as China and Russia.

Universities doing joint research with a foreign university or investors involved in a project involving parties with links to a foreign government would have to register such work in a foreign influence registration (FIR) scheme. Parts of the register may be made public, and non-compliance is likely to be made a criminal offence.

The register has the potential to become a red-tape nightmare — with concerns about it so great that the FIR scheme has been omitted from the present version of the Bill whilst disagreements about its scope are ironed out.

“Seemingly small regulatory requirements readily spawn large bureaucratic responses.”

Writing for the Higher Education Policy Institute in February, the government’s former chief scientific advisor on national security, Anthony Finkelstein, commented that the FIR scheme risked being “too broadly drawn and not based on a grounded understanding of how universities function”. “Seemingly small regulatory requirements readily spawn large bureaucratic responses”, Finkelstein warned.

Nonetheless, the Guardian reports that the FIR scheme will be tagged on via amendment in the coming weeks, whilst the Home Office and Priti Patel both pointedly included reference to the scheme in their publicity surrounding the Bill, implying that an amendment is inevitable.

The delayed registration scheme

According to the government’s consultation document published in May 2021, the basic principle of the FIR scheme is that it “would require individuals […] to register activity within the UK that is being undertaken for, or on behalf of, a foreign state” or “foreign state related actor.”

The Royal Society warned earlier this year that if these terms are defined too broadly, then the FIR scheme could have “a chilling effect on the research community and act as a deterrent to international research collaboration.”

Universities and R&D groups may secure some exemptions from the legislation, but given that the government’s consultation document specifically references “the acquisition of ideas, information or techniques where produced by certain sensitive science and technology sectors”, they may not be able to get much wiggle room.

The language of the consultation document gives some strong hints as to what the government intends to prescribe.

For example, the government explicitly proposed that “non-compliance with the [FIR] scheme should be capable of attracting a custodial sentence”. The threat of a jail sentence underlines the seriousness of the proposals and highlights the need for broad dissemination of the final legislation.

Individuals would be liable. The government stated “that making registration of an activity the responsibility of the individual, rather than an organisation, is likely to be more effective from a compliance and enforcement perspective”. So it is unlikely to be possible for registration to be delegated entirely to dedicated staff – those involved in specific work would have to take on final responsibility for it.

For political and practical reasons, the government is likely to make at least some of the registrable information publicly available.

Conduct “on behalf of” a foreign power

Exactly what activity “on behalf of” a foreign power means is also unclear. During the consultation phase last year, the UK government strongly requested advice on how this should be defined. Whilst expressing certainty that it “should include an element of direction”, the government said that it would “welcome feedback on the various forms of direction that could be included”.

The Bill as currently tabled, which outlines new offences but no FIR scheme, offers a rather broad solution in the form of a “foreign power condition”. This condition is met if the conduct in question is carried out under the direction or control of, with assistance from, or in collaboration with, a foreign power; or if the conduct is merely intended to benefit such a power. The relationship with a foreign government, state or governing party may be direct or “through one or more companies”.

This is the test that will define the new offences if the Bill is passed in its current form. It remains to be seen whether the same or a comparably broad test will be proposed in relation to conduct that will remain legal but, pending the amendment, require FIR scheme registration.

Concrete new offences also relevant

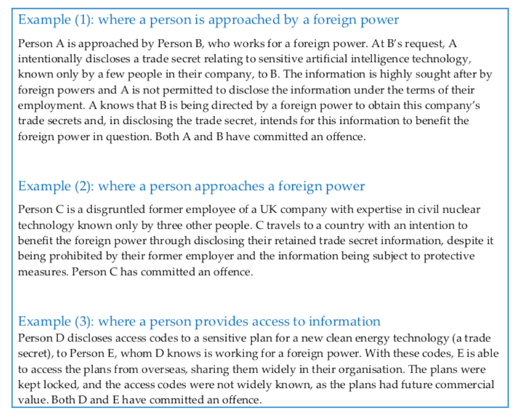

It is also worth noting some of the other new offences proposed in the Bill. For example, conduct meeting the “foreign power condition” that involves unlawful handling of “trade secrets” will become a criminal offence punishable by a fine or up to fourteen years in jail, or both.

It will also become possible to prosecute not only the agents of foreign powers soliciting secrets, but also those disclosing secrets, where the disclosing party “knows or ought to know” that they are dealing with an agent of a foreign power.

The inclusion of “ought to know” clauses is especially important in the context of work involving tightly controlled one-party states. For example, a large number of individuals and entities in the UK are formally associated with bodies demonstrably under the direction of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), such as students & scholars associations or provincial chambers of commerce.

“Within the CCP system, which also extends outside of China, all entities and individuals nominally stand under the Party’s direction,” explains Professor Ralph Weber, who studies the operations of the CCP in Europe. “Yet such direction varies in character and can be hard to define exactly, let alone establish for legal purposes. How the legislation deals with this dynamic will be critical.”

Information about such direction in specific cases, though it may be unknown to stakeholders, is often nonetheless in the public domain – in this instance, on the Chinese-language internet. Future investigators may argue that universities or investors “ought to know” that partners may hold official positions within CCP-directed bodies.

The Bill, if passed in its current form, will also criminalise a broader set of “general” foreign interference where such conduct also meets the “foreign power condition”. For example, if a foreign businessperson misrepresented their involvement with a foreign power to a local government official in order to influence a decision, this would be a criminal offence.

Although it appears broad, the Home Office provides reassurance by estimating that the new legislation will add just 2 to 10 further investigations per year.

The legislation for new offences is really supposed to incentivise greater due diligence on behalf of UK actors, to improve public awareness of state threats, and to deter foreign powers from interfering in the UK.

The (geo)political context

The Bill was originally announced under a different name in the Queen’s speech last year. The government consultation on what was then known as the Counter-State Threats Bill closed last July, but it was only taken further recently.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and MI5’s announcement of a ‘Chinese agent’ operating in Parliament earlier this year, the government came under sustained pressure to accelerate the Bill from Labour, the Liberal Democrats, and some Conservatives.

“There is strong parliamentary demand for a foreign influence registration [FIR] scheme to bring the UK in line with its partners in the US and Australia, so we can expect it to appear in the bill eventually,” says Julia Pamilih, director of the China Research Group of Conservative MPs.

“The introduction of foreign agent registration…is a tricky piece of legislation to get right.”

“But those who have followed the introduction of foreign agent registration in other countries know that it is a tricky piece of legislation to get right.”

A similar scheme in the US, known as the Foreign Agents Registration Act (Fara) has suffered from lack of “enforcement strategy”, proper staffing and legal clout. It contains a broad exemption for scientific pursuits. The Australian scheme meanwhile has witnessed very inconsistent compliance – and even been effectively spammed by former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, a well-known opponent of the scheme.

It is no coincidence that Australia and the US provide a ready reference point for the proposed measures. The two nations are Britain’s partners in the new AUKUS defence grouping announced in September 2021. Both nations have endured recent political scandals relating to political influence exerted by Russia and China – AUKUS’s more-or-less explicit competitors.

Technological competition, especially with China, increasingly appears to be a priority for AUKUS. The UK registration scheme represents at once an attempt to imitate the schemes put in place by its AUKUS allies, and a shifting of emphasis to trade secrets and research and development

Though measures to protect IP and the UK’s technological advantage are deemed necessary across the political spectrum, squeezing legislation relating to innovation, universities and research into a Home Office security bill was bound to be an awkward process. Quite how awkward it will prove remains to be seen. But the underlying motivation for the Bill is unlikely to disappear.

The Bill will have its second reading on the 6th of June.

Sam Dunning is a freelance journalist who tweets from @samdunningo.