China has a policy of superclusters to drive growth and is increasingly incorporating corporate venture capital initiatives into these clusters.

Introduction

Bigger cities are associated with higher productivity and faster economic growth. In advanced countries, the doubling of a city’s population can increase productivity by 2% to 5%, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Connecting people through information and communication technologies as well as by infrastructure to ease commuting expands the scope or reach of the network effects enjoyed by a city or cluster.

China, which has about a fifth of the world’s urban population already in its cities, has taken these ideas and built a policy of superclusters – amalgamating cities in a wider region together – in a bid to use competition and innovation to drive growth and increasingly incorporate corporate venture capital initiatives by state-owned enterprises in these clusters.

Three Chinese superclusters are already well on track: the Pearl River Delta, next to Hong Kong; the Yangtze River Delta, which surrounds Shanghai; and Jingjin-ji, centred on the capital, Beijing. And other regions, particularly in Europe and the US as well as southeast Asia, are de facto forming their own superclusters but as the 20th National Congress in Beijing starts on Sunday, 16th, China looks set to try and take a great leap forward.

Why clusters matter

Much of the traditional cluster theory – developed by Michael Porter, Paul Krugman, Henry Etzkowitz and Loet Leydesdorff from the late 1980s – looked at the relationship between governments, corporations and universities (the so-called triple helix) for why certain areas, such as Silicon Valley, took off economically.

Academics Torger Reve and Scott Stern helped update these theories by adding entrepreneurs and capital to the mix of how clusters form specialisms and related industries.

In Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities, Alain Bertaud draws on over a half-century of urban planning experience to develop the idea of cities as labour markets, according to the City Journal.

Cities are loud, crowded, and expensive, yet people often want to live in them because specialization, employment opportunities and knowledge spillovers create higher-paying and more productive jobs. The productivity gains work both ways as firms pay extra for the hassles and city costs because they depend on the urban areas to find the staff, customers and insights.

Economist Brian Arthur has characterized a complex economy as the interaction of dispersed agents, lack of any central control, multiple levels of interaction, continual adaption and incessant creation of new market niches without a general equilibrium.

As historian Niall Ferguson in his book, Civilization, writes: “Viewed in this light, Silicon Valley is economic complexity in action.”

Returns for venture capitalists in Silicon Valley and other regions follows a power law where size and frequency are effectively along a straight line rather than…a bell curve.

It also means distribution of returns for venture capitalists in Silicon Valley and other regions follows a power law where size and frequency are effectively along a straight line rather than clustered around a mean in a bell curve. Some investors are able to find ways to move up the line and repeat big successes and others always seem to be near the bottom of the line, which is why VC firms show persistence in their returns, albeit with reversion to the mean over time.

As academics Ramana Nanda, Sampsa Samila and Olav Sorenson showed in their study, The Persistent Effect of Initial Success: Evidence From Venture Capital, published in the July 2020 issue of the Journal of Financial Economics, success came from investing in “the right places at the right times” — differences across venture capitalists in their ability to select and nurture specific companies appears to play little if any role in accounting for performance persistence.

Initial success leads to changes in how venture capitalists invest, the academics continued, by being able to invest later, at better rates and select from a wider deal flow. “The picture that emerges then is one where initial success gives the firms enjoying it preferential access to deals. Both entrepreneurs and other VC firms want to partner with them. Successful VC firms therefore get to see more deals, particularly in later stages, when it becomes easier to predict which companies might have successful outcomes.”

But being in the right cluster at the right time, for example around Palo Alto in the 1980s or China in the 2000s, could be often about more luck than judgement.

After all, California’s Silicon Valley as a cluster of dispersed agents – entrepreneurs, investors, researchers, customers and suppliers – is now only one eminent cluster among thousands.

Consultant Christian Rangen has tracked about 7,000 of these clusters as an emerging global phenomenon. He said: “By our estimates, between 3,000 and 5,000 of the global clusters could be counted as emerging clusters. They are just starting out. Emerging clusters have a low number of members, frequently in the range of 35 to 75 members. They have a very limited resource base, with limited funding and often only one full-time cluster manager, supported by one to three part-time resources.

“We estimate between 2,000 to 3,500 of all global clusters would qualify as growth clusters. At this stage, the cluster management team has grown, often counting five to eight full-time employees. Membership has grown, frequently counting from 100 to several hundred members, usually but not always paying members.

“Globally less than 100 clusters qualify as an innovation supercluster.”

“Globally, we estimate less than 100 clusters would really qualify as an innovation supercluster. A supercluster is recognized by the size and membership base, but even more importantly by the value impact or value creation in the supercluster. We find that successful superclusters have far higher value creation then their peers. They also tend to have a much larger export share and just naturally work and compete globally.

“The best superclusters, over time, become strong magnets, widely recognized as global innovation hotspots in their field, drawing international capital, researchers and startups into the cluster.”

Modern travel and communication methods have extended the reach of the cluster (see box) creating greater knowledge sharing and innovation capabilities, which China is trying to grasp over its peers.

China’s plan

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, China changed its assessment system of global strength and national progress to put less emphasis on military strength and more on the importance of economics, foreign investment, technological innovation and the ownership of natural resources, according to Michael Pillsbury, author of The Hundred-Year Marathon, China’s secret strategy to replace America as the global superpower.

Pillsbury’s well-argued contention is the secret strategy was developed from stratagems used in the Warring States period leading to the first Qin dynasty ruling the country (from which we have the word China) more than 2,000 years ago.

These stratagems, collected in the book, The General Mirror for the Aid of Government, which was the only one carried by Mao on the Long March the Communists took in the 1930s, set out how to use deception and manipulate your opponent’s advisers, steal your opponent’s ideas and technology for strategic purposes, avoid encirclement and induce complacency in the incumbent hegemon.

Mao’s writing, Pillsbury found, “were filled with Darwinian ideas” of competition and survival of the fittest. But one where natural selection means the losers are eliminated as Darwin’s translator, Yan Fu, described it through Pillsbury: “The weak are devoured by the strong and the stupid enslaved by the wise so that, in the end, those who survive… are most fit for their time, their places and their human situation.”

Using competition, therefore, between startups and state-owned enterprises, between regions and with other countries as a means to identify the strong from the weak ideas and allocate resources efficiently and effectively is a powerful tool to service a system of government by the Chinese Communist Party. Competition can also be used as a means to undercut potential rivals by changing the regulatory or business and financing environment.

As Foreign Affairs noted: “Traditional explanations for China’s rise have focused heavily on the stealing of intellectual property. Although that has played a role… innovation is viewed as a social and economic process, one that can be guided and accelerated with the right mix of physical resources and bureaucratic resolve. Although China’s approach contradicts Silicon Valley’s deeply ingrained assumptions about the necessity of free markets and free speech, it has yielded more technological advances and commercial success than most American experts believed possible.

“The first step in that process, one that took place from 2000 to 2010, was for China to create a large, semi-protected market. Fostering a nascent innovation ecosystem required markets to be lucrative enough to fuel fierce competition, but it also required some degree of protection so that the established juggernauts of Silicon Valley did not come in and steamroll local startups before they could get off the ground.

“Beginning around 2008, Chinese engineers who had worked at Google began returning to China to found their own startups, bringing some of Silicon Valley’s culture with them. Researchers at Chinese universities began collaborating more with their peers abroad, which exposed them to fresh approaches. Chinese tech companies studied their competitors in the US and Europe, ingesting the latest tech trends and adapting them to the Chinese context.

“Once the market conditions and international connections were in place, China took the third step, unleashing a wave of resources: investment capital, physical infrastructure, trained engineers, and bureaucratic energy…. The Chinese government’s 2017 artificial intelligence initiative, for example, set an ambitious goal: making China the world’s preeminent AI hub by 2030. But its biggest impact was a wave of experimentation and activity across the Chinese bureaucracy and private sector. Mayors built sparkling new AI startup accelerators in their cities. Agricultural officials created pilot programs for smart fertilizer drones. Public hospitals partnered with universities to create medical AI research institutes. And police departments across the country spent lots and lots of money purchasing surveillance technology.”

As Fitch Ratings noted in the summer, there has been a surge in the number of privately owned enterprises (POE) transferring controlling rights to state-owned entities (SOE).

In Fitch’s study of China A-share listed companies, transfers averaged around 50 per year from 2019 to 2021, up from less than 10 in 2017. High-tech manufacturing companies are the most popular strategic investment targets, its report added.

Regional and local SOEs were the most active investors, accounting for 90% of deals, while economically developed coastal provinces were the most active markets. Aside from bailing out financially challenged POEs, SOEs have been investing “to acquire key technology and assets, promote local industrial upgrades and to obtain listed company shells for back-door listing,” Fitch said.

The data in last summer’s report in the Journal of Banking & Finance already showed partially government-owned VCs, especially by provincial governments, increased the likelihood of a successful exit, especially via initial public offering (IPO) in mainland China, where the IPO process is discretionary and heavily regulated.

This diversification of experimentation under central control helps explain why China is now trying to turn itself into a country of 19 super-regions with the planned city clusters far larger than any others around the world. As the Economist noted, the population of its cities has quintupled over the past 40 years, reaching 813 million people.

To put the scale of China’s plans into context, the biggest existing city cluster in the world is around Tokyo in Japan, home to some 40m people. But, when it is fully connected, the Yangzte River Delta (YRD) around Shanghai will be almost four times as big, with 150m people.

The average population of the five biggest clusters that China hopes to develop is 110m.

The average population of the five biggest clusters that China hopes to develop is 110m. The Pearl delta (also known as Greater Bay Area, GBA) around Hong Kong is expected to cover 42,000 square kilometres, about the same as the Netherlands the Economist notes, as the speed of transport links, notably the bullet trains between cities, means commuting areas can be measured by time rather than distance.

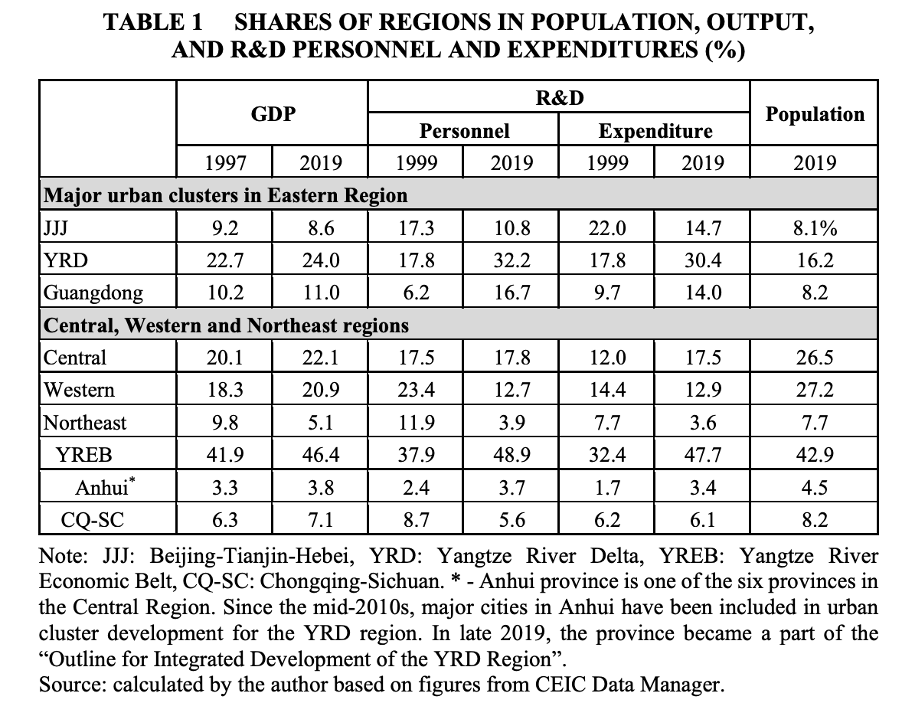

Sarah Tong, senior research fellow at the East Asian Institute of the National University of Singapore’s, analysis of China’s development plan said: “Regional development stands out as one major component of China’s recently-released, 14th five-year plan (the outline). [It] recognises three urban clusters, the JingJin-Ji [JJJ, around Beijing], YRD and GBA, as focal points to enhance China’s ability to innovate and take a lead in high-quality development.

“Further, the outline itemises important tasks for the three major metropolitan areas for the coming years and technological advancement-related projects are featured highly.

“For the JingJin-Ji region, an important undertaking is ‘to improve the capabilities in basic research and original innovation of the Beijing S&T [science and technology] Innovation Centre, to give play to the pioneering role of the Zhongguancun National Indigenous Innovation Demonstration Zone, and to promote further integration of industrial and innovation chains among the three’.

“Such an emphasis on S&T and innovation is even more pronounced in the planning for the GBA and YRD. On the GBA, the outline specifies a number of major projects, including to strengthen coordination in industry-university-research among Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macau; improve the ‘two corridors and two points’ framework; promote the construction of a comprehensive national science centre; and facilitate the cross-border flow of factors for innovation.

“Similarly, the major tasks for YRD are innovation related, including attaining internationally advanced science and innovation capabilities and an industrial system, accelerating the construction of YRD’s G60 Science and Technology Innovation Corridor and industrial innovation belt along Shanghai-Nanjing, and improving YRD’s ability to utilise global resources and drive growth of the country.”

New York University’s Bertaud told the Economist that China’s city clusters could, thanks to their size, achieve levels of productivity never seen in other countries. He told the Economist it would be comparable to the differences between England and the rest of the world during the Industrial Revolution.

Jerry Engel, professor at University of California, Berkeley, warned China’s latest initiatives to develop their entrepreneurship and innovation ecosystem or clusters were likely to face significant headwinds. Its underlying economies lack the precedent conditions of a strong experience base of technology entrepreneurs and investors.

He added by email: “Certainly, consistent government support, through a combination of progressive policy and investment in science, human capital and market development, can accelerate and enrich the ecosystem. However, the rate of progress, and innovation ecosystems’ ability to become self-sustaining, has limiting factors and overinvestment will only cause its own disruption.

“The relative size of the ecosystem’s population is not directly correlated to its productivity. True, a large domestic market for the innovations enables and accelerates their success, and perhaps even their eventual global consumption. But this is an advantage on the demand-side of the equation.

“Moreover, it is the behaviours of the supply side that are the key. Namely: the mobility of resources (money, people, technology), entrepreneurial behaviour (relentless pursuit of opportunity and resources), business practices that align interests (shared risk and reward), a global perspective (market opportunity and resource acquisition) and global linkages.”

Douglas Hansen-Luke, founder of university spinout-focused venture capital firm Future Planet Capital, added also by email: “All other things being equal, China should lead the world with its population. But, for China, there is less freedom than elsewhere and this will continue to hamper the development of its centres of innovation.

“Future Planet Capital signed its first cooperation agreement with Tsinghua University in 2016. Arguably the top university in China, we would love to invest in [Tsinghua’s] founders or scientific spinouts. Unfortunately, uncertainties over capital controls, IP [intellectual property] and political freedom mean that we have not yet made an investment.”

The role of corporate venturing in China

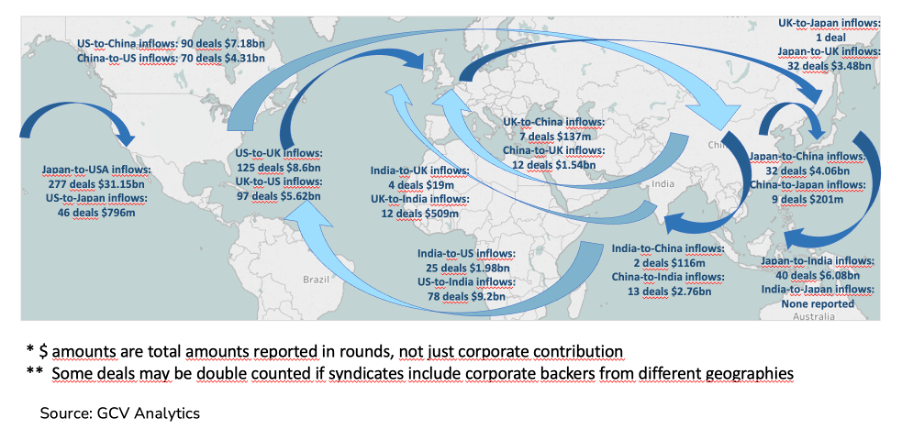

The so-called Great Firewall over the past 15 or so years has not just protected China’s local entrepreneurs from competition in their markets but also limited the corporate venturing activity from international investors.

From the 1990s, when then-US-based publisher International Data Group (IDG) started CVC in China, foreign investors picked up key stakes in local superstar companies. Around the millennium IDG invested in search engine provider Baidu, Japan-listed telecoms operator SoftBank and internet services provider Yahoo backed online retailer Alibaba, and South Africa and London-listed publisher Naspers (now called Prosus) acquired its large minority stake in games developer Tencent (in a secondaries transaction from IDG). (Collectively the three were known as BAT.)

With broadly protected home markets enabling first survival and then plenty of free cashflow to invest, the three internet superstars then started their own corporate venturing activities.

In probably the most valuable advice ever given was from Prosus to its portfolio company Tencent to look at corporate venturing as a way to partner and support its ecosystem rather than kill of nascent competition.

A dozen years later and Tencent has more than 800 portfolio companies including 120 unicorns, as the Economist noted but under local authority pressure has started to sell down its large stakes in other listed companies, such as retailer Meituan worth about $24bn, according to Reuters. (Here’s the GCV analysis on China’s evolving ecosystem from earlier in the year and here.)

Similar moves by Alibaba and Baidu resulted in comparable large returns and holdings, with the BAT’s portfolio companies also setting up active CVC units and the methods copied by newer scale-up success stories, such as Xiaomi and Bytedance.

Having built up China’s private sector through allowing competition and transfer of knowledge, the government has cracked down on the largest companies over the past year, such as by halting the planned flotation of Alibaba’s financial spinoff Ant and preventing new releases by Tencent, in order to encourage the next generation and weaken any nascent political desires they might have.

This seems to be encouraging companies, such as Tencent, to invest in more companies outside of China, such as in UK-based gaming platform Haidion alongside the UK and US’s national security funds, NSSIF and IQT.

Together the demand and supply-side reforms underway in China around superclusters is creating a dynamic challenge for western governments roiled by elections, economic pressures and inflation, and worsening demographics.