Having less than $50m in capital is challenging for a corporate VC fund. But with the right approach and in the right sector it can work.

A rash of small CVC funds were created in 2025. More than 10 new funds have been launched since the start of the year with capital of $50m or less, by companies as diverse as Tennis Australia, which set up a $30m sports tech fund, Japanese broadcaster TV Asahi, which set up a $35m fund, and Perplexity AI, the AI-powered search engine, itself still a three-year-old venture-backed company, which set up a $50m AI fund.

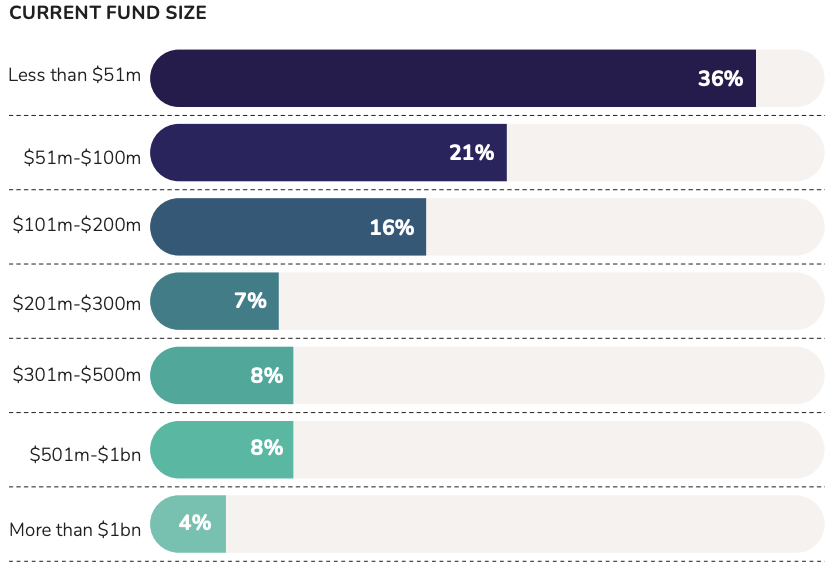

Many corporations — around a third according to Global Corporate Venturing’s latest annual survey — operate a fund that is $50m or less, especially if they’re trying corporate venturing for the first time.

For more data on the corporate venture industry see GCV’s World of Corporate Venturing report.

A difficult investment climate over the last three years, when startups have struggled to raise new rounds and stock market listings have been scarce, has tempered many companies’ enthusiasm for making big bets on emerging companies.

“Basically, the board says: ‘Let’s take it easy. Let’s write a $10m, $15m, $20m ticket and start the learning journey from there’,” says Peter Van Gelderen, partner at venture capital firm Icos Capital.

Taking a small first step into the market may be fiscally prudent. But it can be difficult to run a successful VC-style fund with such limited capital, says Van Gelderen.

“Fifty million dollars would be kind of a minimum, a $100m would be preferred,” says Van Gelderen. Set-up costs of the unit, salaries and overheads alone can swallow up upwards of a million dollars, and the team will have have to either invest very small cheque sizes, or back only a few companies.

“And then in five years, four or five years, the money is gone, and they haven’t done much.”

Many corporations with small venture budgets invest money with VCs like Van Gelderen’s Icos Capital, which pulls together several corporations with similar interests, pooling their cash to give them more fire power.

But others want an approach that puts them in closer contact with startups and would prefer their own fund, even if it is small. With the right approach, says Marshall Smith, managing director at First Rate Ventures, a micro-fund can still be highly effective.

How First Rate Ventures makes $20m go a long way

First Rate Ventures, set up in 2022, is the investment arm of a family-owned, business-to-business banking software company First Rate. The fund has $20m in capital, and tends to invest cheques of around $500,000 in early stage companies, at the rate of two a year. It has made five investments so far.

Smith makes his budget go further by offering a “sweat equity”-style exchange with startups. First Rate has a loyal customer base with big banking customers and a lot of in-house expertise in building software. In addition to giving startups cash, First Rate also gives them access to market channels and staff — including their banks of offshore developers in India.

“We can help early-stage companies raise less money because they don’t need to build the teams, because they can leverage our team when needed, they can go to market faster because they don’t have to rebuild everything or learn it all from scratch. They can sell through our channel. They can take all of our enterprise product experience and leverage it to build a better, faster, ultimately more enterprise ready product,” says Smith.

Sometimes, he says, First Rate doesn’t have to offer the startups a cash element at all, as the operational benefits are enough.

“We can help early-stage companies raise less money because they don’t need to build the teams, because they can leverage our team when needed, they can go to market faster because they don’t have to rebuild everything or learn it all from scratch.”

Marshall Smith, First Rate Ventures

This kind of barter arrangement is also often seen with corporate funds in the media industry, where startups can be given advertising and media exposure rather than cash in exchange for an equity holding. The Times Group, for example, has had success with this model in India and last year set up a new investment arm, Mercurius Media Capital, to try the system out in the US. Mercurius Media started with an allocation of just $55m.

With a $20m fund, First Rate Ventures is also targeting a very specific type of startup. “Hot” rounds and high-profile AI startups that command premium valuations are strictly off the menu.

“We’re not chasing Sand Hill Road founders on their second rodeo, who can raise a $25m pre seed round with a PowerPoint deck. There’s no reason for us to chase that,” says Smith. He’s not investing according to the so-called power law where investors back 10 companies, knowing that most will fail but one or two will provide outsized returns.

“We flip it. We want to invest in 10 companies, with only one or two going to zero. We want seven or eight of them to survive and become cash flow positive,” says Smith.

The returns that First Rate Ventures achieves may not get VC pulses racing, but they are solid, and in some cases very rapid. It’s first investment three years ago was putting $500,000 into a seed-stage company. First Rate went on to set up a partnership with that company which has so far generated $2.5m in revenues. Overall, the parent company has been so satisfied with the venture unit’s results it is now planning to expand the fund to $30m.

Are small funds more founder-friendly?

About half the founders get the proposition, says Smith.

“I find that founders, if they’ve not taken traditional venture yet, actually see that that’s more founder friendly,” he says. “They know they’re pumping sunshine at Silicon Valley VCs. They know that path is unsustainable and they’ll get wrecked. I have a different vision for growth. Raise less money, go to market faster, reduce your burn.”

At a time when the VC industry has become less bullish and funding rounds can be harder to raise, this approach is increasingly appealing for some founders.

One of the problems with this approach, however, is that it may only work in some niche situations where a barter arrangement is valuable. A specialist CVC like Perplexity VC may get away with being small because its expertise in AI is so highly valued, but not every micro-CVC will have this clout.

Micro-CVCs may also find themselves restricted to investing in seed-stage startups, which can be challenging because they take so long to mature.

“Very early stage companies are only interesting for the technology director or CTO. You have to sit on the investments for 15 years, which is incompatible with the normal corporate cycle,” says Van Gelderen.

“If you really want to do something closer to business, you have to get into series A, B, C companies that have a product and some revenue. That’s where the interesting action is. But to get in those rounds, you need to be able to put in $3m, $4m, $5m, maybe $10m. If your budget is $10m for five years, then it’s not going to work,” says Van Gelderen.

First Rate Ventures might be fortunate that it is a family-owned business and can therefore take a longer-term view. It also operates in a field, B2B software-as-a-service, where companies grow quickly. A micro-CVC strategy would be much more challenging in a slow and capital intensive field like hardware.

Ultimately, says Van Gelderen, there is no single optimal size for a CVC fund. Much depends on the situation and, above all, the company’s aims for engaging in corporate investing.

“If your objective is to have some view on the outside world, you can probably do it with a little bit of money,” he says. “If your objective is to become part of some of those great companies that are being built, you have to put more money in.”

Maija Palmer

Maija Palmer is editor of Global Venturing and puts together the weekly email newsletter (sign up here for free).