Supply chains are not just subject to geopolitics, they are the stage for it. But are corporations investing enough in this?

“In a multi-polar world defined by war, trade conflict and technological rivalry, your business strategy is now a geopolitical strategy” said retired British general Richard Barrons earlier this year while delivering a keynote at an event for Swiss startups.

That’s especially true in the supply chain and logistics sector – which concerns itself with physically moving goods around the world and across legal regimes, forming the backbone of the global economy.

When geopolitical conflict flares, the supply chains are one of the first areas to be targeted, and political pressure tends to translate into supply chain pressure. Sanctions, trade embargoes, export controls and, in more severe cases, cyber attacks on ports and logistics IT, are available levers. Just last month, for example, the insurance costs to ship goods through the Red Sea more than doubled amid attacks on ships from Houthis in Yemen.

In the context of global supply chain, there are two major pillars that have been shifting – one faster than the other – in consequential ways, according to Dennis Groseclose, founder and CEO of supply chain management services company Transvoyant, which has on its cap table investors including MSD Global Health Innovation Fund. The first shift is the undermining of the decades-long global trade stability.

The second is a shift to a multipolar world, where all political power isn’t concentrated in one or two superpowers. We are moving towards more complex, disparate economic and trade policies among more blocs, as well as more adverse action – kinetic and otherwise – by both state and non-state actors.

“Non-US based multinationals actually look at [US trade turbulence] as an opportunity,” says Groseclose

“They’re saying to me, if you can help us see risk, predict risk, see geopolitical issues quicker, and then design, plan and execute a predictive supply chain, then we don’t necessarily have to be so dependent, you know, on the US as a market or as a supplier.”

Investors and startups need to understand that geopolitics and the security of supply chain are now design constraints – they need to be woven into the ROI calculations and need to take a prominent place in due diligence. These considerations are not just tail risks.

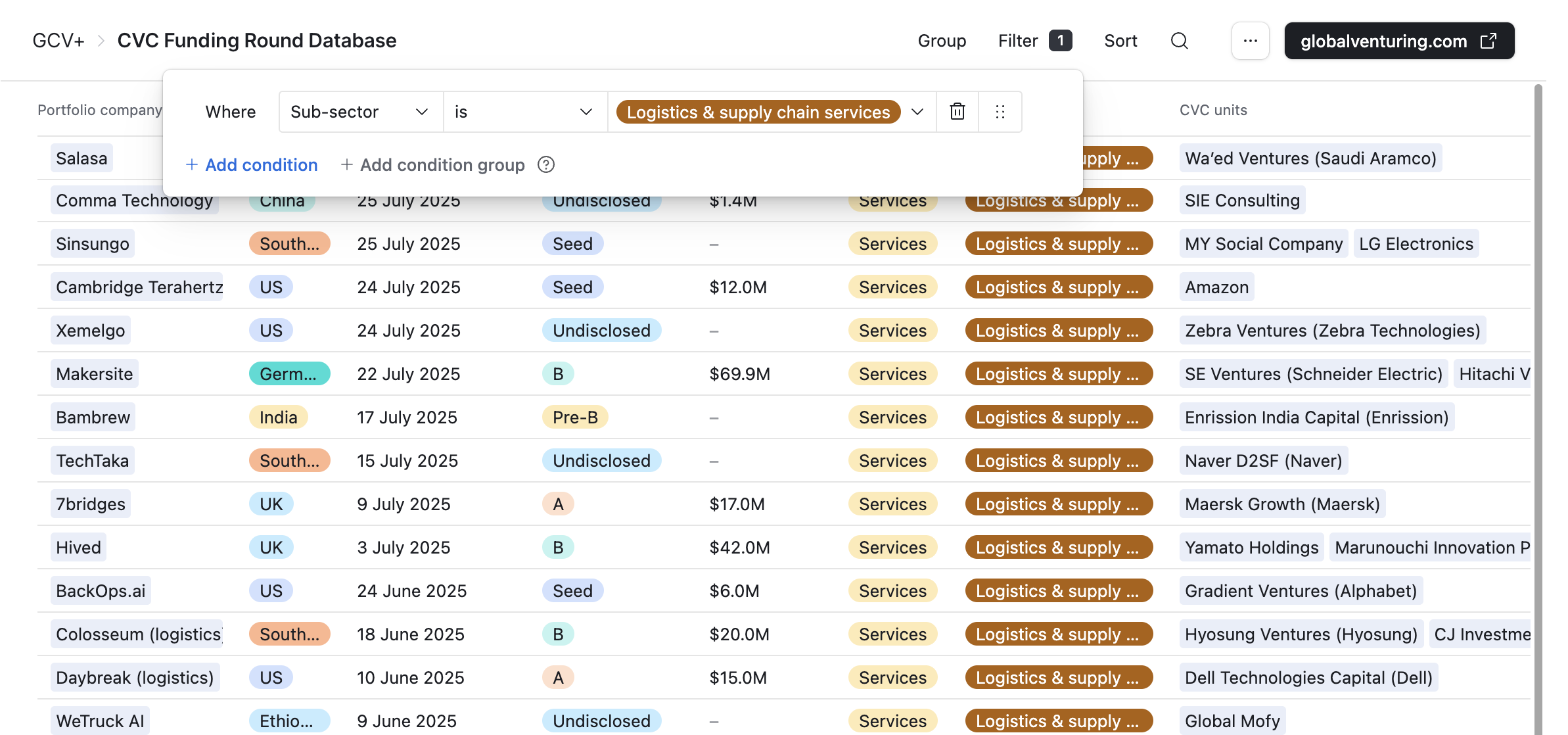

Yet corporate investments in logistics and supply chain-related startups have been gradually trending downwards since 2023. Some of the biggest corporate investors in this area are Amazon and Maersk. But Maersk has slowed down its rate of investing in this area — having made four investments in 2023, it has subsequently made just one more, investing in UK-based supply chain optimisation platform 7bridges in July.

Companies in industries with complex and vulnerable supply chains, such as energy, mobility, also make occasional investments in logistics startup. Toyota and Yamaha Motor, for example, invested in logstics platform Shippeo earlier this year, while Qualcomm backed supply chain monitoring software provider Tive.

See all the logistics startup funding rounds backed by corporate investors since 2023 in The CVC Funding Round Database.

More and smaller nodes

Companies have typically carried out capacity planning – where to produce, where to ship, how to move things – on a yearly or half-year basis. Today, that needs to change, says Groseclose. Capacity planning needs to happen more frequently and companies need to proactively monitor geopolitical risk.

What used to be called supply chain resiliency, is really the ability to predict and mitigate the impact of political and security risks quicker and more frequently, says Groseclose. Groseclose, who was previously vice president of homeland security at Lockheed Martin and also had a technology role with the US Transport Security Admistration (TSA) founded Transvoyant as a way of giving all business more visibility of these kinds of risks.

“Before the Red Sea closes down because of the Houthis, we can predict that has a chance of happening,” he says.

One way businesses can be more resilient is by distributing their manufacturing “nodes” – factories, warehouses, distribution centres – and making them smaller, modular and more distributed. Instead of having a small number of large manufacturing hubs in a few places, businesses would have a several smaller hubs across a larger area, allowing for greater flexibility and faster movement and adaptation to supply chain shocks.

Groseclose says small companies are not thinking about this enough.

“ When I had to go brief Lockheed’s board, this always came up. But never on a small board did it come up to ask what if half a development need needs to be moved from Country A to Countries C and D,” he says.

“If you think about talking to investors, that’s the kind of stuff they have to start thinking about. This is a problem and opportunity. It is going to accelerate,” he says.

Not all industries can be modular

Modularising the supply chain is not feasible for every industry. The phenomenally high CAPEX, equipment, and economies of scale needed to efficiently manufacture semi-conductors – ironically some of the most geopolitically touchy products – mean they would large manufacturing hubs.

Pharmaceuticals are a different story. The cycle times of designing, testing and approving a pharmaceutical product are notoriously long, but once the formula is set, the production cycle times of are short, even with high quality standards.

Active pharmaceutical ingredients tend to be liquid, can be made in manageable batches that can be distributed geographically, can be moved closer to the end markets, and can provide a more flexible network if some nodes are closed off.

Human capital

Even if a business doesn’t ship physical items around, it will have people. Businesses may have staff in different countries to take advantage of cheaper labour pools, or to have a presence in the countries their clients were in. Whatever the reason they also need to have contingency plans for them if regional tensions flare up.

Transvoyant itself did this in Ukraine. They had contingency plans in place, and moved hundreds of people to other countries in a matter of days when the fighting began.

Signal vs noise

Figuring out what the real risks are for a business requires careful filtering. There can be a lot of noise on social media platforms from policymakers saying things for effect. US trade policy pronouncements, for example, have tended to be walked back, delayed or modifie , causing market players to tune them out.

But reading smaller, disparate data points can point to more serious risks. For example, malignant actors might be looking to take action at a particular canal, which can be picked up and avoided.

What worries Groseclose the most are not the obvious actions of a state, it’s the more subtle ones that are not easily attributed.

“ I have seen, in the past, changes in the behaviour in a node – which could be anything like the slowing down or strikes at a port, and you can multiply that times 5,000 other nodes around the world – and if you dig into the nodes, airports, and ports and bridges and toll roads, etc., you’ll find that they’re often owned by or heavily influenced by state actors,” he says.

Putting all these individual signals — whether a strike, or a fire, or a slowdown in aeroplane throughput at particular ports — together can show a pattern of disruptions around the world. When most people see that kind of stuff, the cause tends to be irrelevant to them, either way their business is being disrupted, but as it happens more and more, its harder to see them as random isolated incidents.

“I’m confident that some of it is state-sponsored,” says Groseclose

“It’s these subtle – same with cyber – economic disruptions. Before you know it, someday somebody can’t get vaccines and then those people are in the street with a riot.”

Supply chains will be a primary place for state actors to flex their muscles and test out capabilities, and if and when the conflicts kick off, they will be a primary battleground.

Fernando Moncada Rivera

Fernando Moncada Rivera is a reporter at Global Corporate Venturing and also host of the CVC Unplugged podcast.